Because I moved during the pandemic, I met my landlord and neighbors while we were all wearing masks. For months, these new people in my life existed only from their hair, eyes, and forehead to the upper bridge of the nose—until New York City, like many places in the U.S., eased up on mask regulations and recommendations. Since I’m vaccinated, I mostly stopped wearing my mask when outside.

Recently, on the street, I saw the unmasked face of one of my neighbors for the first time. He looked completely different than I expected. I wasn’t consciously aware I had been making a prediction of what his whole face looked like, but I had been—and I was very wrong.

Videos by VICE

This is a phenomenon that will likely happen all over the country, and world, as people encounter each other with their faces uncovered for the first time. The surprise I felt is partly explained by a feature of the brain called amodal completion—when we predict and fill in missing perceptual information—and also by the fact that we’re pretty lousy at perceiving faces unless we see the whole thing.

During the pandemic, we’ve gone through a massive change in the way we identify and see people in our surroundings, said Erez Freud, a cognitive neuroscientist at York University in Canada. He called 2020 the “biggest experiment in face perception that was ever done.” How else to get a large percentage of the human population to walk around covering their faces—especially in parts of the world where masks were previously not culturally accepted?

Humans are especially sensitive to seeing faces; it’s why we can see them in electrical outlets or other inanimate objects, a phenomenon called “face pareidolia.” “We see faces even when they’re not there,” said Anthony Little, a reader in the department of psychology at the University of Bath in the UK. “It highlights the importance that faces have for us.”

But this sensitivity has some parameters, Freud said. He explained that our brains are prone to process faces in a specific orientation and combination—upright and with two eyes, a nose, and a mouth. This is called holistic face processing, which means we look at and recognize faces as a whole, and not by just specific features.

The images below might not immediately look like faces, just bowls of vegetables. But if they’re flipped, they suddenly, and irrevocably, look like the faces of some jolly vegetable people.

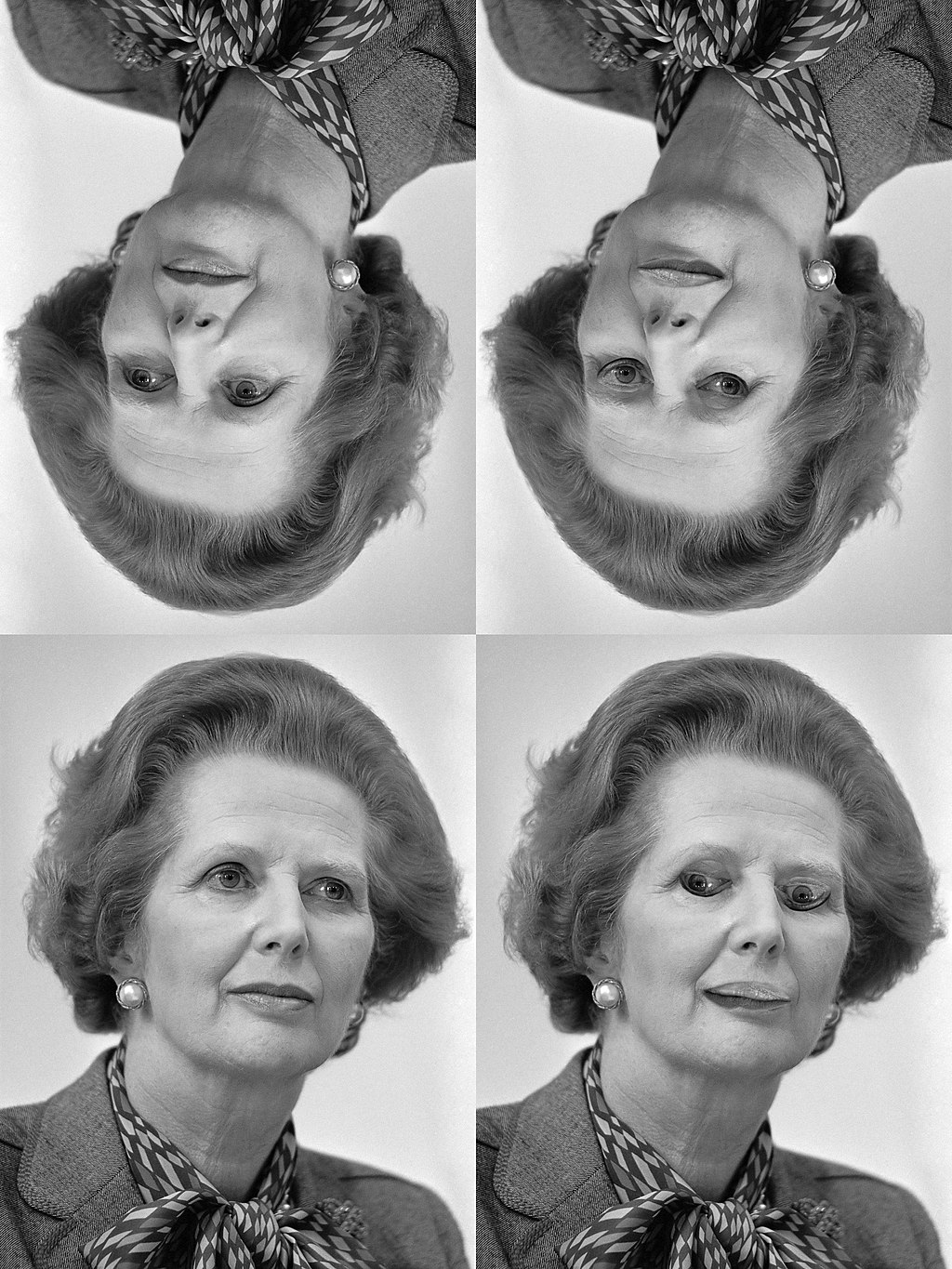

People with face blindness, or prosopagnosia, have been found to have disruptions in holistic processing—an indication of how important this type of processing may be. This can also be revealed in the face inversion effect, which is when people, even without face blindness, aren’t as easily able to perceive faces when they are inverted.

An example of this is the so-called Thatcher illusion. When these faces are upside down, it’s more difficult for us to determine that something might be awry. When they’re flipped to the correct orientation, we’re able to easily perceive that Margaret Thatcher on the left has had her features distorted.

When we process masked faces, we do so in a less holistic fashion, since we’re only seeing half of a face. This may be the underlying mechanism as to why we’re less able to identify faces when they’re covered. Freud and his colleagues found last year in nearly 500 people that their ability to perceive masked faces was markedly decreased, when compared to their ability to perceive unmasked faces. In 13 percent of people, it impeded their ability to perceive faces enough that it was on par with prosopagnosia.

Freud showed me the below example, in which a masked face has the same eye region, but the women’s whole faces are quite different from one another. Once you see the face holistically, it’s impossible to think they look the same. But with parts of their faces covered, we don’t perceive that.

When we see a covered face, we also perform amodal completion. Normally, when we perceive the world around us, there are sensory inputs that reach our sense organs, like information hitting the retina, which then gets processed by the brain into a representation of what we’re seeing. But in some cases, like when a mask is covering the lower half of a face, there is no sensory input. That’s when amodal completion steps in to fill the missing parts.

In these examples, “the only things that are visible in the image above are really just the black triangles arranged in a certain way,” wrote Bence Nanay, a cognitive scientist at the University of Antwerp, in Psychology Today. “But you see a spiky sphere. The sphere is not visible, strictly speaking, but you can’t not see it. On the right-hand side, you see a sea monster, but those parts of the sea monster that are underwater are not visible. Your perceptual system completes these invisible parts.”

Amodal completion can occur with all of the senses, not just vision. If you’re talking to someone on a busy street and a car honks in the middle of their sentence, you complete what they said, even if the auditory signal of their words didn’t reach your ears.

When people wear masks, our retinas don’t get any visual input as to what their nose, mouth, and chins look like. How we amodally complete the lower half on someone’s face is largely based on memory, said Vanay. If it’s a person you already know, your episodic memories of that person will drive what you fill in below the mask. That doesn’t guarantee it will be accurate.

“If you haven’t seen your friend for a long time, you’re still filling in that part of the face on the basis of information that’s two years old,” Nanay said. “A lot might have changed since then.” As T.S. Eliot wrote, “What we know of other people is only our memory of the moments during which we knew them. And they have changed since then.”

Of course, if it’s a person you’ve never seen without a mask at all, memory isn’t much help. “That’s when things get really interesting,” Nanay said. “In the cases of masks, your visual system is using generic information about what noses and mouths look like to complete the face.”

And it turns out, when it comes to faces, we often amodally complete with attractive features. A study from 2020 found that when people assessed the attractiveness of faces in complete and incomplete photographs, they thought people in incomplete photos were more attractive. The authors wrote that during an “information shortage,” people are more likely to be positively biased when it comes to another’s looks. This was shown in another recent study from 2020, which found that people who were thought to be average looking were seen as more attractive when wearing masks.

This effect may have been enhanced because of the pandemic. A study from before COVID-19 found that in Japan, women wearing masks were perceived as less attractive than those without masks. When the same authors studied the topic again recently, they found that “the perception of mask-worn faces differed before versus after the onset of the COVID-19 epidemic.” Specifically, they found that masks now improved a person’s level of attractiveness.

“You are unlikely to amodally complete a large red pimple on the nose behind the mask, but some people do have pimples on their nose,” as Nanay wrote. “The top-down generic information amodal completion provides is, in some sense, idealized information.”

Scott Barlett, a surgeon at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and co-author of one of the attractiveness studies, said that he was acquainted with this side effect of masks even before COVID.

“When we were young residents, I can’t tell you how many times you fell in love with a woman in a surgical mask across the table, only to be disappointed when she took her mask off at the end of the case,” he said. He said there were even slang terms for it, like “mask love,” or “mask hot.”

What information was my brain using to fill in my neighbor’s face? If I didn’t have any memories to rely on, I was making a generalization based on my previous experience with noses and mouths. Intriguingly, my boyfriend was not at all surprised by how our neighbor looked. That means that my amodal completion was less accurate than his, and that we completed our neighbor’s face differently from one another. It could be that my partner and I have different visual diets, Little said, or exposure to faces in our past histories, and social media and television.

We amodally complete all the time, but we typically don’t notice or care as much about our errors. When you look around a room, there’s almost nothing you’re not amodally completing. “When you look at a chair, what’s behind the chair—you’re amodally completing,” Nanay said. “Looking at your phone, you’re amodally completing the back side of your phone. But these are not super exciting features of objects.” Faces, on the other hand, are an emotionally charged and salient stimuli, so they garner more attention and surprise.

A year with masks is one way to remind ourselves how much of what we perceive doesn’t come from the outside world, but comes from us. Little said people often believe they can predict someone’s personality from their faces, and that we make assumptions about others based on their expressions. These predictions can sometimes be right, but many times they’re not.

Freud and his colleagues did a more recent study to see if after a year in masks, people were better able to perceive masked faces. They found in over 300 people that they didn’t improve at all, which suggests that in adults, experience doesn’t lead to an increased ability to perceive faces un-holistically. “It emphasizes the rigidity of the matured visual system, even with naturalistic experience and training,” Freud said.

Needless to say, this decrease in ability to perceive others’ faces is an interesting lesson in facial perception, but not a reason to avoid wearing masks, which were and are a crucial public health initiative to prevent the spread of airborne viruses. It’s just a friendly reminder that what we see when we don’t see, is more complex than it first appears—especially when it comes to faces.

“Are we just walking about the world, being wrong about how we amodally complete things? Yea, that’s partly true,” Nanay said. “Our visual system has to do a lot of guessing at any given time, and some of it is going to be wrong. This is just a real life, one and a half year long demonstration of that.”

Follow Shayla Love on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

-

Nassau County Police Department -

-