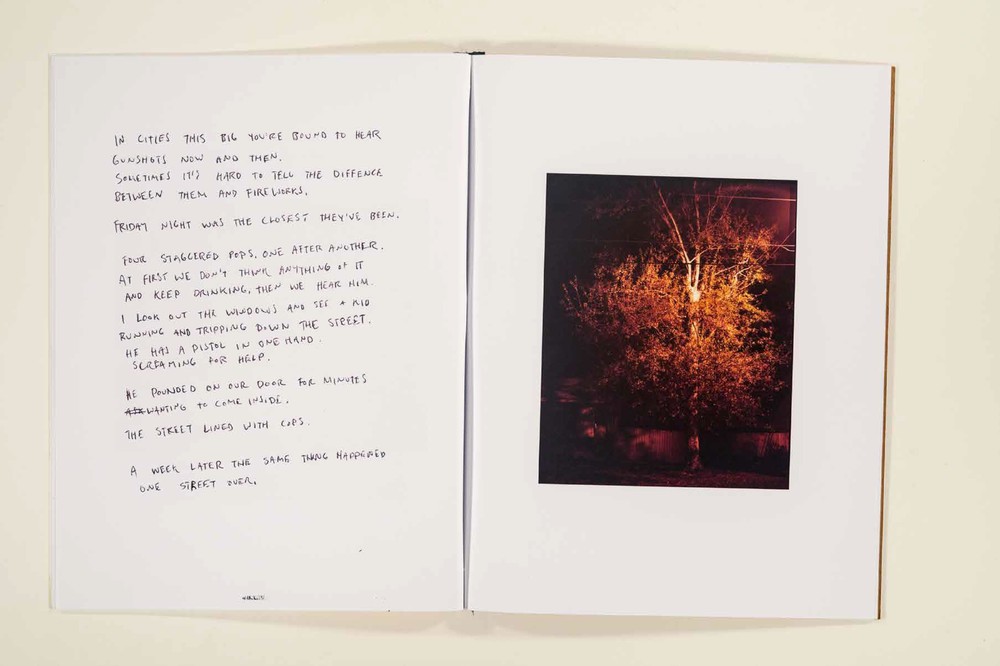

Installation Image of Common Sense(s)

Common Sense(s) is a show currently on display at the Center for Photography at Woodstock, New York, that features a compilation of photozines and related ephemera by over 50 artists. Juan Madrid, a previous VICE contributor and staffer at the Center, co-curated the impressive display with artist Carlos Loret De Mola. Since I’m the photo editor of VICE’s IRL physical magazine (which you can subscribe to here) I think a lot about paper and ink and why we keep them around. At a time when people can get all their news and scroll through a zillion photos before they’re out of bed, what’s the point of putting a printed object out? Finding communities and people who are like-minded make me feel a little less insane about the fight for printed matter so I asked Juan and Carlos a couple of questions about the show and their own thoughts about the final fate of print.

VICE: Why make a show about zines?

Juan Madrid: I love printed matter. It’s an obsession, and zines are a direct manifestation of that obsession in a much more democratic way than photobooks. We’re also in a golden age of printed matter, and exploring what can be considered a zine, along with the influence that zines have had on the world of photography to this day, is something I find immensely interesting. Where do lines get drawn in considering what a zine is, and why?

Videos by VICE

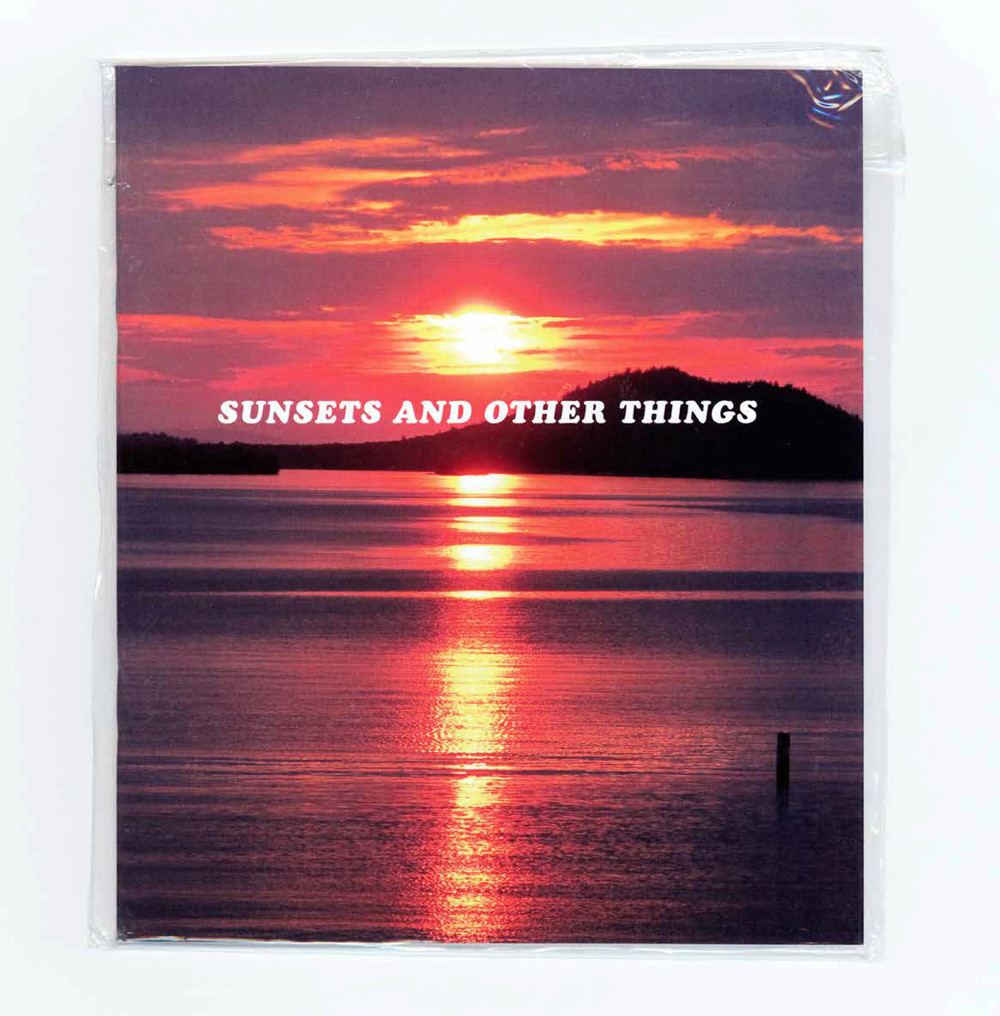

Carlos Lore: The purpose was to compile an idiosyncratic showcase for one of the most forward-thinking and provocative areas of current photographic practice. Independent artist publishing has been experiencing an explosion of activity over the last decade. Within that activity, the “photozine” has emerged as a platform for lens-based artists to publish their work with a raw and experimental urgency that more traditional forms of independent publishing lack.

What do zines mean to you?

Juan: They’re a lot of different things. In creating them, they’re a way of making something that doesn’t have to hold the same weight as a fully-fledged photobook—they can be a way of exploring more experimental ideas quickly or act as sketches or drafts of something bigger.

It’s also a way of having a built in community—there are many small zine fairs across the country and it’s so easy now to meet people who share the same passion for creating them. There’s a pride that comes with having made something by hand and that’s a shared sentiment among those who make them.

Carlos: We use the term zine in a very contemporary manner that respects its roots but also attempts to explore its current state. A lot of the energy that went into producing the “fanzines” of the late 20th century is now residing in the blogosphere, where fans can indulge in just about any obsession instantaneously. People that are making zines today are as obsessed with zinemaking itself. The process relies on its independent, artist-made nature. Zines tend to connect the artist more directly with its intended audience, as opposed to a trade publication or a bespoke edition where the imprint of the publisher or gallery or other institution bodes heavily in that connection.

Do you think it’s worth it to create them?

Juan: Of course it’s worthwhile! Nothing can replace the tactile, despite the pervasiveness of digital in nearly every aspect of modern life. At least for the time being, print still has a life—it may change as younger generations grow up in an increasingly digital world.

Carlos: All the artists in this project are committed to the contemporary photo zine as a primary form for creating original work. They value the look and feel of these very tangible paper-based publications that they imbue with immediacy, intimacy, fervor, and transgression. They are eminently accessible objects with often challenging content. They can be instantly experienced by anyone anywhere at anytime without a monitor screen or a rechargeable battery. Yeah, they’re totally worth creating

Why do you think there’s a resurgence of people dedicated to making them?

Juan: The inexpensive nature of producing zines definitely doesn’t hurt. But more importantly, I think zine-making is a fairly inclusive venture—even though it can seem like white males dominate it, there are many non-white artists using the zine form, both in print and digitally, to engage with vital ideas that need to be out in the world. Common Sense(s) brings many of these artists and ideas to a broader audience, asking them to not only engage with the work, but to open themselves up to different perspectives.

Carlos: I’m not sure I would call it a resurgence. Steady, increased accessibility to digital printing technologies has definitely expanded the field of practitioners over the last several years. More artists are experimenting with the potential of independent publishing today than ever before and the zine platform has its own unique appeal. Even very established artists as varied as photographer superstar Gregory Crewdson and narcissistic pop super genius Kanye West are using the zine form to distribute their distinct ideas.

Who are some of your favorite artists featured?

Carlos: Forcing me to pick is tender cruelty. These five artists just happen to be on my mind:

Devin Morris’s 3 Dot Zine is a unique platform that focuses on works by artists concerned with issues of race, gender, and beauty that tend to be marginalized in our society. It combines a very provocative mix of surrealist imaginings and treatments along with a spare and elegant design.

Alejandro Cartagena’s current independently published output, including Before the War and Headshots, are biting commentaries on the realities that have recently defined contemporary Mexico, including the violent war against the drug cartels and the empty, laughable promises of President Enrique Peña Nieto.

Louie Palu is an award-winning documentary photographer who produces and distributes his own newspapers. They are newsprint tabloids covering various stories including life in cartel-controlled Northern Mexico and life in Guantánamo prison. He edits and designs them himself, lending him full control over his stories and how they are told.

Terranova is an independent publishing unit in Barcelona with a distinct rebellious mandate: to create beautiful, tangible, physical publications by a new generation of artists that are “being silenced or removed from the mainstream by the capitalist structures dominating the national cultural scene” in Spain. Their stuff is steeped in youth, idealism, and open community.

Michael Max McLeod’s zine series Casual Encounters consists of photographs he took of men that he found on online dating sites. Each zine is titled after the name of his subjects. These zines are succinct, intimate, and voyeuristic. They are not explicit, but they do portray a kind of collaborative event between McLeod and his “hook up’s” that speaks to the nature of sexuality, technology, and mutual revelation.

Why is it called Common Sense(s)?

Carlos: Our curatorial process began by considering Thomas Paine’s influential political pamphlet “Common Sense” from 1776 as a point of departure. Paine was a prolific independent publisher whose objective was to alter the status quo. We wanted to highlight artist publishers that highly value their independence and are creating challenging, provoking work. The variant “Common Sense(s)” was chosen to reflect the visceral engagement these artist publishers all share.

Common Sense(s) is currently on view through April 10 at the Center for Photography at Woodstock. It is running alongside two other exhibitions: Welcome: Page by Page (a selection of artist’s books curated by Hannah Frieser) and Stolen Portraits (a series of collaborative portraits by Richard Edelman). Viewing hours are noon to 5 PM.

Juan Madrid is an artist and curator based in Upstate New York. You can follow his work here.

Carlos Loret de Mola is an artist and curator based in Hudson, New York. You can follow his work here.

More photographs from the catalogue below