This article originally appeared on VICE Italy

During the two decades of Mussolini’s fascist regime in Italy – from 1922 to 1943 – thousands of people were imprisoned in asylums, simply for not conforming to the morals held by the regime. Annacarla Valeriano and Costantino Di Sante, researchers from the Italian University of Teramo, spent years studying first-hand accounts of the inhumane imprisonment of the thousands – especially women – who were considered mentally ill for being too liberal and “morally abnormal” to function in society.

Videos by VICE

Their study turned into an exhibition – featuring photos, medical records and personal letters – which was on display in Rome’s History Museum last year and is now travelling around Italy. I spoke with Annacarla about their work, and about exactly what the regime did to women who didn’t listen.

VICE: How did this project come about?

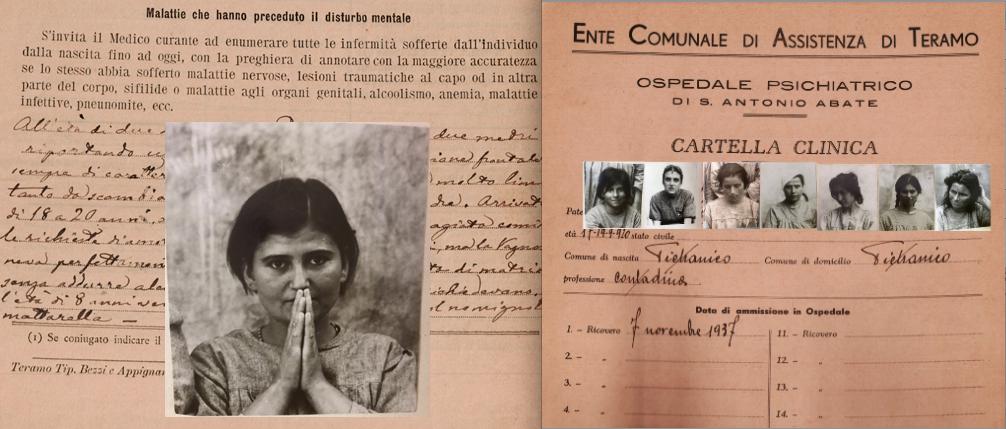

Annacarla Valeriano: In 2010, we started looking into the archives of the Sant’Antonio Abate asylum in Teramo, which was founded in 1881 and closed down in 1998. For one study, I analysed the medical records of 7,000 out of the 22,000 men and women who were incarcerated there between 1881 and 1945. Part of that research was featured in my book, The History of Teramo’s Asylums. After the book was published, I decided to go back and focus only on the women who were hospitalised during the 20 years of fascist rule, from 1922 to 1943.

Why? What was so interesting about them specifically?

During the fascist era, mugshots started appearing on the women’s medical records. And in those years, more and more women were being admitted to the asylum for “deviancy”. I found the concept of “female deviancy” fascinating, so I decided to look into it.

Why were the mugshots significant?

According to positivist theory, which was popular then, you could tell if someone was a criminal or mentally ill simply by their skull dimensions, by the shape of their cheekbones or the position of their eyes. And the photos also served a practical purpose – the patients could be easily recognised if they tried to run away.

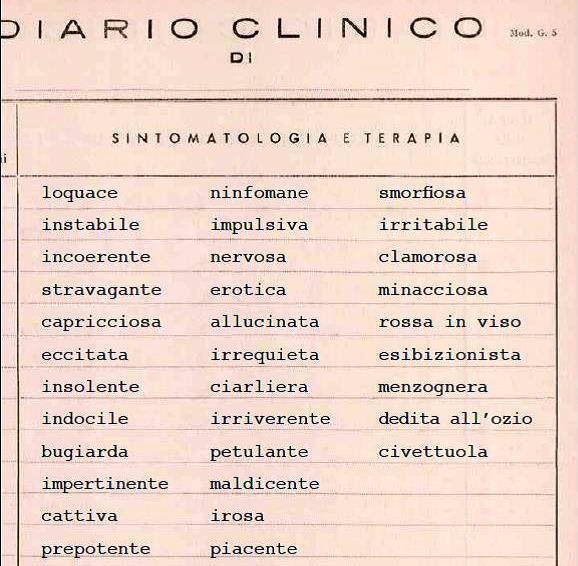

What were these women diagnosed with, exactly?

With “deviancy”, but the state created many categories of deviancy. In a famous speech in 1925, Mussolini said that the only role a proper wife had to play was that of a good mother. Most of the women who were hospitalised were accused of being “degenerate mothers” – they didn’t fit the model of what the state believed a mother should be.

Were women of a certain class especially impacted?

Most were working class women living in severe poverty. They worked out in the fields, and had ten, 12, 14 children. If they ever became overwhelmed by their responsibilities – complicated further by famine and extreme poverty – and they were unable to look after their families in a way the state thought acceptable, they were labelled as “degenerate mothers”. The same was said of women who suffered from postpartum depression, or who were unwilling to have more children. They didn’t fit with Mussolini’s image of the perfect housewife.

And what about sexual deviancy? The fascist government introduced state brothels, so they didn’t mind prostitution, but weren’t many women institutionalised for sexual issues?

Yes, we did find records of some sex workers, but their profession was not the problem. They were often only hospitalised in the asylum if they had contracted an STI. But according to the regime, the real problem were girls and women who refused to fully submit sexually to the will of their partners. They were seen as rebels and needed to be subjugated.

Did any of the women’s stories particularly touch you?

I was moved by so many of their stories, I couldn’t help but feel an intimate connection with them. What hit me hardest were the letters they wrote, describing their experiences in their own words. Those letters were often addressed to their families, but they were never sent. Instead, they were simply attached to their medical records. In most of those letters, they pleaded with their families to take them back, or with the clinic’s staff to release them. Some wrote down accounts of their daily lives, filled with abuse, control, inhumane living conditions and starvation.

They were incarcerated, but was there any treatment?

The imprisonment itself was supposed to be a form of treatment. Until medication for mental health issues was introduced halfway through the 20th century, isolation and custody were deemed sufficient treatment. And at the time, they thought behavioural abnormalities and mental health issues were the same thing. If you were a man unwilling to work or a woman unwilling to listen, you were believed to be “constitutionally immoral”.

What other forms of treatment were there, aside from keeping them in custody?

In the early 20th century, mental health issues were thought of as an organic imbalance, and they were treated with cycles of hot and cold baths, and the so-called “rest cure” – which meant patients were tied to their beds for long periods of time. During the fascist era, doctors would experiment with insulin shock therapy, electroshock therapy and even malariotherapy – which involved injecting patients with malaria to raise their body temperature to extreme levels in the hope of “shocking awake” a catatonic patient. These kind of experiments were incredibly dangerous.

Did people ever get released from the asylums?

Sure, I’ve found many cases of people sectioned, released and then sectioned again several times. That mostly affected women who didn’t have any family to return to. Usually, when people died in the asylums, or spent 50 or 60 years locked up, that was because their relatives weren’t willing to take them back. Once you were sectioned, you stopped being a person. You were deprived of your human rights and labelled a criminal. It was a source of great shame to have a relative in a mental health institute.

The way we deal with mental health issues has improved, but what has stayed the same, in your opinion?

We still need to break stigmas attached to mental health issues. For example, after a murder, one of the first things you hear is that the killer was “a psycho” or mentally unstable, like that explains everything. And there’s still some violence and abuse in some mental health institutions. Those might be isolated incidents, but we need to do more to prevent them.

Thanks, Annacarla.