If you’ve taken oral contraception, you’re probably familiar with the concept of placebo pills—a week’s worth of inactive tablets taken at the end of the month. Because these don’t contain hormones, taking them triggers what’s known as “withdrawal bleeding,” which mimics a period, along with fun menstruation-related symptoms like cramping and diarrhea. You have also probably wondered, at least once, whether or not you can just skip ahead to next week’s hormonal pills, staving off the bleeding in order to preserve the inviolability of your new sheets or looming beach vacation plans.

In fact, although the majority of oral contraception brands include inactive pills in their packages, there’s no actual medical justification for this—gynecologists have deemed withdrawal bleeding medically unnecessary for years now. For many women on hormonal birth control, this raises a very valid question: Why the hell am I bleeding every three weeks if I don’t have to be?

The answer, weirdly, lies within the Catholic Church. The church views birth control as a sin, with one important exception: “A married couple would not be sinning… if the husband and wife knew that natural reasons prevented them from having children,” according to Jonathan Eig, a journalist who has written an extensive history of the development of the pill. Under prevailing church dogma, the “rhythm method“—in which married couples track their ovulation cycle and engage in non-procreative sex during the “safe periods” where the woman isn’t ovulating—is natural in this way.

Videos by VICE

Read More: The Racist and Sexist History of Keeping Birth Control Side Effects Secret

This byzantine and slightly confusing belief matters because one of the scientists who helped develop the birth control pill, John Rock, was a devout Catholic. He was convinced, however naively, that the church would accept the pill as a form of “natural” contraception if it were presented in the right light. (Because the pill contains progestin—a hormone naturally released after ovulation, during the “safe period”—Rock considered it a sort of scientific extension of the rhythm method.)

But in order for it to be palatable to the church, he knew that it had to seem natural. And if women took the pill consistently, with no withdrawal periods, they’d potentially go months without any menstrual bleeding—which would freak pretty much everyone out. Rock and his collaborator Gregory Pincus thus decided that the pill should be subscribed in four-week cycles consisting of “three weeks on the pill and the fourth week off the drug (or on a placebo), to allow for [withdrawal bleeding],” Malcolm Gladwell writes in a 2000 New Yorker story. “There was and is no medical reason for this.”

In 1960, the pill was approved by the FDA; eight years later, the Pope publicly rejected Rock’s argument, declaring all forms of “artificial” contraception to be against church doctrine. By that point, however, it didn’t really matter what the church thought: The withdrawal period had already become an integral part of the birth control regimen. And to this day, the pill is fundamentally “a drug shaped by the dictates of the Catholic Church—by John Rock’s desire to make this new method of birth control seem as natural as possible,” as Gladwell puts it.

When the pill first appeared on the market, under the name Enovid, it didn’t come in the dial pack that we now associate with birth control. It was sold in a vial, like any other medication, and it didn’t contain any placebo pills. Instead, it came with instructions advising women to take five days off, every 20 days, in order to allow for withdrawal bleeding.

Although these instructions were fairly straightforward—20 days of pills, five days off, repeat—some consumers were apparently worried that women would find them confusing or forget them altogether. In 1961, an Illinois-based father of four named David Wagner started looking for some sort of mnemonic solution after his wife, Doris, began taking the pill. “I found that I was just as concerned as Doris was in whether she had taken her pill or not,” he later recalled to Patricia Gossel, a science historian. “I was constantly asking her whether she had taken ‘the pill,’ and this led to some irritation and a marital row or two.” After a bit of “noodling around” with the design, as he put it, he arrived on a slightly more complex version of the round pill dispenser we know today, which gives women a clear visual indication of whether they’ve taken the right pill on the right day.

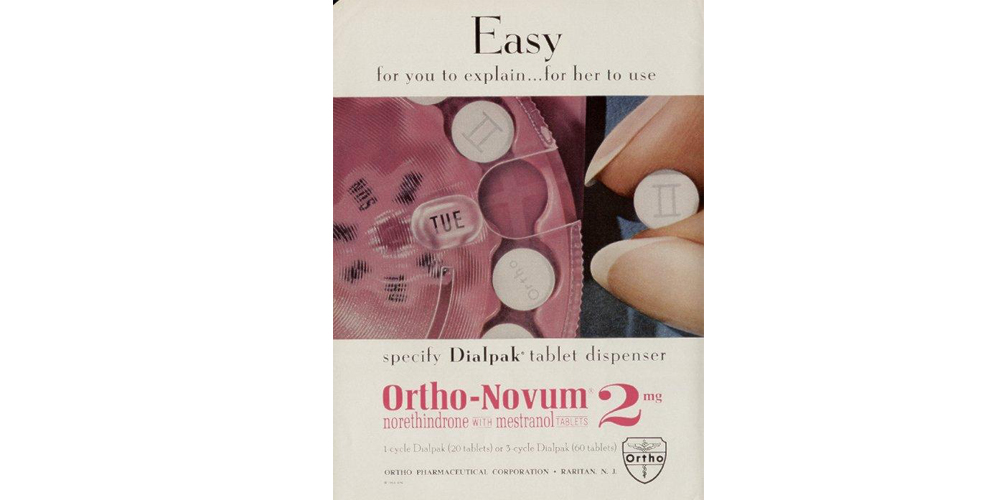

By the mid-60s, pharmaceutical companies had started selling the pill in dial-shaped packs, with clear indications illustrating when women should commence their monthly withdrawal bleeding. From this point on, the specter of women’s “forgetfulness” stubbornly attached itself to the discourse around birth control. A slew of ads targeted at physicians encouraged a paternalistic approach, depicting women as “scatter-brained, incompetent, and in need of guidance,” Gossel writes. A 1964 ad for oral contraceptive Ortho-Novum featured the slogan “The package that remembers for her.” Another, by the same brand, read, “Easy. For you to explain… for her to use.” A 1969 ad for Lyndiol urged doctors to “protect the new patient from her own forgetfulness.”

In 1965, a brand called Oracon became the first to include placebo pills in its packaging. Oracon’s most documented motivation behind the first placebo pills was to help women ensure that they were taking their pills correctly: Inactive pills meant that women now took a pill every single day, thus putting them on a more routine schedule and making it easier to notice if they’d missed one. Of course, the pill’s engineers could have just as easily added an extra week of active pills so that women were still taking one a day. That, however, would have meant that women no longer bled once a month, and the 60s weren’t quite ready for that.

This formula—three weeks of hormonal pills, followed by one withdrawal week, complete with the requisite bleeding—remained unchanged for over 40 years. Then, in 2003, the drug company Barr released Seasonale. This was the first oral contraceptive to give women the option of foregoing monthly withdrawal bleeding; it contained 84 hormone pills and seven placebo pills. Women using this method would experience withdrawal bleeding just four times a year—or once per season, as the drug name intimated. Four years later, the FDA approved Lybrel, the first oral contraceptive to offer continuous active pills with no breaks for withdrawal bleeding whatsoever.

With the release of so-called “menstrual suppressing” contraceptives like Seasonale and Lybrel came lively debate about the safety and politics of skipping periods. Some experts were concerned, warning that there was no reliable data on long-term effects of menstrual suppression. “There are [still] a lot of people that think that it wasn’t healthy. Some, when that drug came out, said, ‘Look, we’ve never had a huge patient population take this drug… it’s like all these people taking Seasonale are part of a medical or pharmaceutical experiment. We just don’t know what the long-term risks are,” Dr. Andrea Tone, a professor at McGill University and author of Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America, told Broadly. “Then you have people on the other side that say, ‘If we give women a pill… that suppresses menstruation for the rest of their reproductive lives, that’s a really good thing. Why should women have to go through 400 menstrual cycles?’”

Why should women have to go through 400 menstrual cycles?

In their marketing campaigns, both companies highlighted the freedom that fewer periods a year would give women. Seasonale ads featured women dancing, traveling, and biking in all-white outfits, with slogans like “Let’s hear it for four periods a year,” and “Fewer periods, More possibilities.” (Critics, however, said that these companies downplayed the fact that many women taking the pill experienced heavy breakthrough spotting, and in 2005 the FDA sent the pharmaceutal company behind Seasonale a warning letter condemning their ads for understating this side effect.)

On a philosophical level, Seasonale and other extended cycle pills ignited a conversation about what it means to have a period, and whether our eagerness to suppress our menses is reflective of internalized patriarchal forces. In 2006, a filmmaker named Giovanna Chesler tackled the surprisingly controversial subject in an hourlong documentary, Period: The End of Menstruation? “Women are not sick,” she told the New York Times in an interview the following year. “They don’t need to control their periods for 30 or 40 years.”

A vocal group of feminist activists agreed with this assessment, arguing that skipping your periods is unnatural and that marketing menstrual suppression products sends the wrong message to girls: that there is something wrong with menstruating. “These messages underscore that women’s natural functions are defective, dysfunctional, and in need of medical intervention,” Chris Bobel, a women’s studies professor and author, told Ms. magazine in 2010, neatly summing up this line of criticism. “How is this feminist?”

Other women had a less political reason for wanting to keep their monthly withdrawal bleeding: Many use it as a way to ascertain whether or not they’re pregnant, a method that gynecologists confirm is reliable. (Though, they warn, bleeding is not uncommon during the first trimester of pregnancy.)

Those in favor of menstrual suppression—including many feminists—argued that allowing women to choose whether or not they wanted to endure their periods or withdrawal bleeding was a long-awaited step in the right direction, especially since the side effects hardly differ from those of regular oral contraceptives. This group also disliked the idea of equating menstruation with womanhood, which they saw as reductive gender essentialism. A majority of menstruating people seem sympathetic to this side: A 2006 survey on menstrual suppression by the Association of Reproductive Health Professionals found that “few women have an emotional connection to their period,” and that only eight percent of women “enjoy their period in some way.”

Read More: How Messing with Your Birth Control Affects Your Body

Today, the science is more settled, though there hasn’t been a long-term study on the continuous use of oral contraceptives yet. But based on data from the long-term use of non-extended cycle birth control pills, which are chemically the same as extended cycle contraceptives, gynecologists have largely reached the conclusion that the practice is safe. “At this point, I can’t think of any OB/GYNs that would have a problem with [extended cycle oral contraception],” says Dr. Lauren Naliboff, a fellow at the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

A study by the Cochrane organization found that women on extended cycle pills “fared better in terms of headaches, genital irritation, tiredness, bloating, and menstrual pain” than those on pills with monthly bleeding. A peer-reviewed article by Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica acknowledged that long-term studies are lacking, but ultimately concluded that continuous use oral contraceptives showed no unique side effects beyond increased spotting, and still resulted in less “bleeding days” than non-continuous birth control pills.

Philosophical and scientific debates aside, perhaps the largest barrier between women and their right to decide whether or not they want to bleed is a lack of information. Many women are unaware that consistently skipping withdrawal bleeding is an option, let alone that extended cycle pills exist, or that menstrual suppression can also be accomplished with hormonal IUDs, NuvaRing, birth control injections, and contraceptive patches.

For More Stories Like This, Sign Up for Our Newsletter

The invention of the pill was one of the most significant advancements in the fight for reproductive agency; it allowed us, as a society, to dramatically reconceptualize sexuality and gender relations. At the same time, our relationship to this groundbreaking medical technology has been shaped and constrained by our own conceptions of what’s “natural” and what defines a woman. Similar reproductive and sexually liberating advancements that target men—Viagra, for instance—have not led to similar debates on what it means to be a man, or to have an “unnatural” hard-on. And while Viagra is covered by insurance, Dr. Naliboff says that most insurance companies do not cover extended cycle birth control to this day, even in cases where patients are on the pill for medical issues like primary ovarian insufficiency or endometriosis.

The discrepancy in education and affordable access is telling: The normalization of placebo pills and subsequent withdrawal bleeding means that even in 2017, many women do not know that extended cycle pills exist, let alone that menstrual suppression is a safe option. Combined with the fact that the percentage of schools teaching students about contraception has declined drastically since 2000, this means that many women are likely to stay in the dark about their options when it comes to choosing whether or not they want to bleed once a month.