All this time, you thought witches were supposed to be brewing up potions in those big, bubbling cauldrons. But what if we told you that instead, those massive black pots were full of a more popular poison: beer?

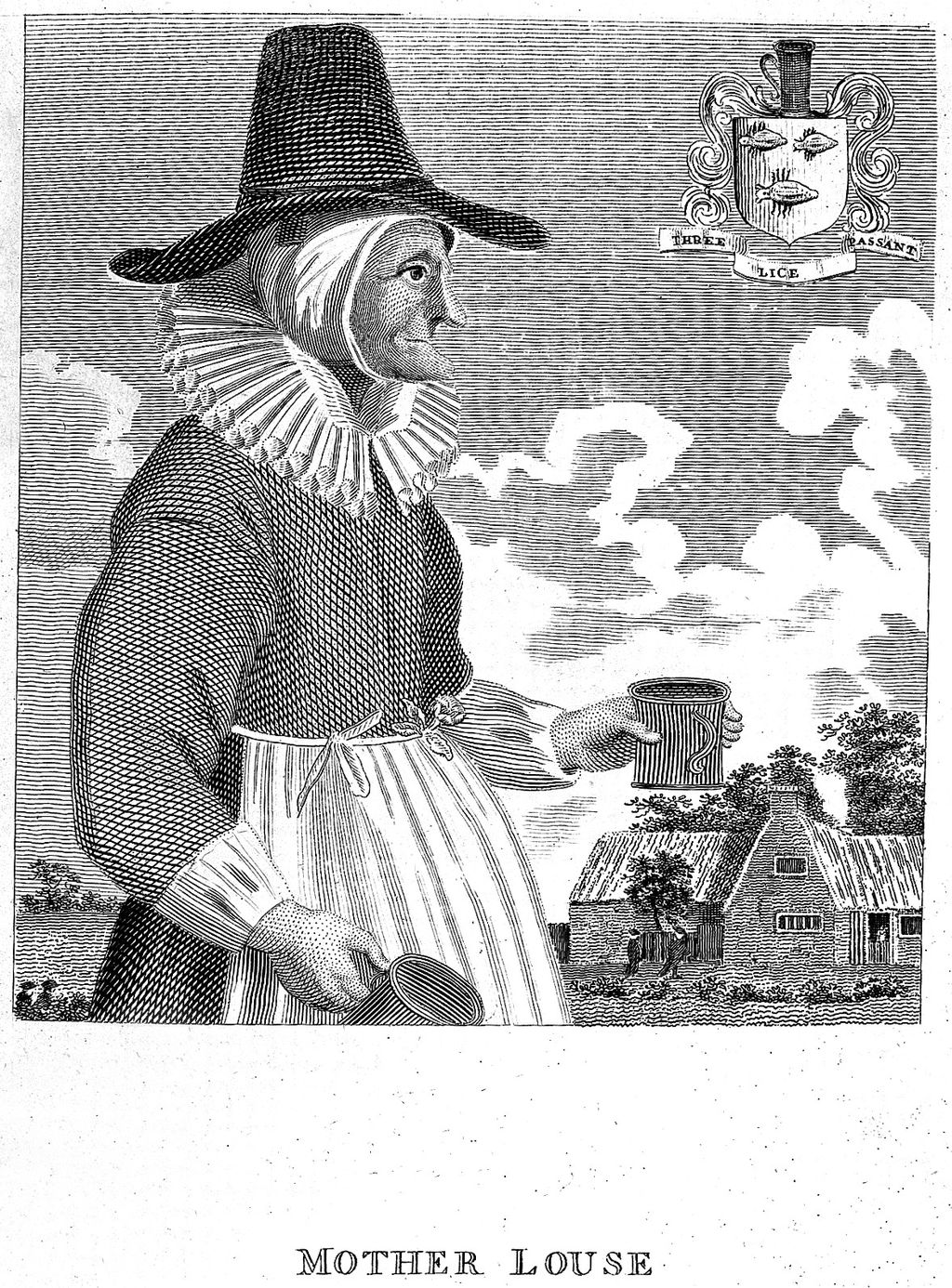

As far as Halloween decorations and elementary school literature is concerned, witches are frequently portrayed as a craggy old woman with wispy gray hair, a big hooked nose, a pointed black hat, and maybe a broom. Those latter two accessories have historically also been tools of the once-female-dominated ale brewing trade, a connection that historians have been puzzling out for decades. Yep—historically speaking, those ladies in big pointy hats might have actually been brewing ale.

Videos by VICE

Women who brewed ale at home were known in medieval Europe as “alewives,” and they did so as part of their normal routine of domestic duties. While in contemporary America, beer brewing is often dominated by hyper-masculine stereotypes and entrepreneurship, ale brewing—much like butter churning or bread baking—was considered well within the domain of the woman’s sphere of work within the home. It was as much of a necessity of life as any of those other chores, given that fermented beverages were often safer to drink than water. And like butter, cheese, or any other homemade foodstuffs, if a household could produce enough beyond their own immediate needs, the women of the house often took their goods to market to make a little extra money.

In order to catch as many eyes as possible, and to signal from a distance what they were selling, these “brewsters” wore tall hats. As a cottage industry, there was very little oversight or regulation to the home-grown brewing businesses, according to Rod Phillips in the comprehensive text Alcohol: A History. But there were also large-scale commercial breweries, widely owned by men, which were leveraging new technologies and making larger quantities of product. As these operations grew and took on the appearance of a “real” profession, with guilds and trade associations, women were by and large excluded.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, small-scale ale producers, mostly brewsters, began to face accusations of a whole host of immoralities that caused irreparable damage to their reputations. According to Judith Bennett, the preeminent historian of women brewers in this period of England’s history, both the public and the male-dominated brewing industry accused brewsters of diluting or adulterating their ale with cheaper brews, and thus of cheating customers. Brewsters were also accused of selling tainted ales that could make drinkers sick, perhaps intentionally. And generally speaking, at this time, a woman having a working knowledge of herbal concoctions and medicines was highly suspect, and might face rumors that she was using her knowledge for nefarious ends. Thus, the sign of the humble alewife’s hat came to be associated with all the same evil maliciousness of a poison-peddling witch.

Some historians deny the veracity of this association, such as Dr. Christina Wade of the blog Braciatrix, devoted to the history of women in brewing and bartending. She argues that during the later Middle Ages, when images of brewsters in such tall hats come into the historical record, witches weren’t yet associated with them. (Let alone the fact that it’s unlikely that brewsters across Europe, a rag-tag assembly of home-spun brewers to begin with, collectively agreed on the tall hats as a form of marketing.)

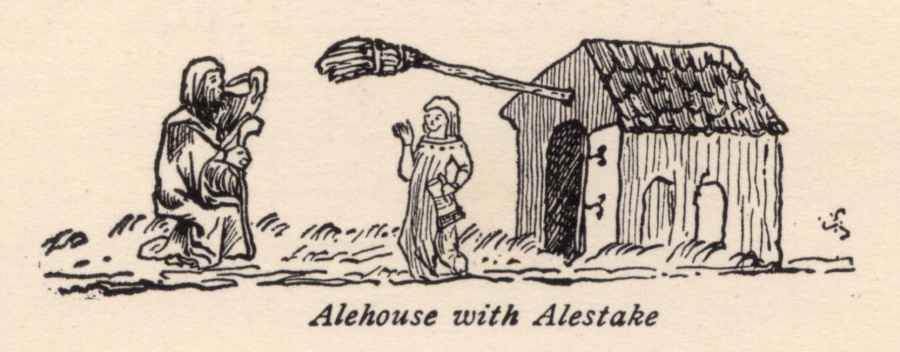

She also questions another common connection drawn between brewsters and witches: that the broomstick leaned against the outside door frame of a home signaled that there was a cauldron full of ale inside, ready for customers. While the signal to that effect—called an “alestick”—was definitely a thing and was intentionally used to flag down passersby, there’s little to suggest that it was unanimously agreed upon that such a stick would have to be a broom.

Regardless of the origins of the myth, one fact remains eerily, spookily true: that in history, the domestic work of women has often been devalued and erased by men who came to dominate the industries that were built on those skills, especially any skill that was important in the kitchen. And that, dear readers, is something that sends a chill down our spines… and is a spell we’d like to break.