The steep hills and canyons of Malibu are prone to fast-moving wildfires, but the one that broke out on November 24, 2007 was especially destructive. The Corral Fire burned nearly 5,000 acres in just four days, driven by 60-mile-per-hour Santa Ana winds and fueled by bone-dry chaparral. By the time firefighters contained it, more than 80 structures lay in ashes, among them an old ranch house containing a grand piano that had once belonged to Neil Diamond.

A few months after the fire, Korn frontman Jonathan Davis stood before the house’s charred remains, his two young sons in tow, crying. “You don’t know,” Davis told them. “This place was really something special. It started a whole movement of music.”

Videos by VICE

Korn had recorded its first two albums in that house, a former hunting lodge turned recording studio called Indigo Ranch. The music they created would come to be known as nu metal, a term Davis despises. “I cringe when I hear that word,” the 47-year-old tells me by phone from his LA-area home ahead of an afternoon songwriting session with his band. “But I guess you have to call it something.”

Whatever you want to call it, Korn’s 1994 self-titled debut did start a movement, and Indigo Ranch was its hub. Over the next six years, a procession of bands—Limp Bizkit, Soulfly, Cold, Human Waste Project, Machine Head, Amen, Slipknot—trekked into the Malibu hills to record some of the decade’s angriest and most polarizing music, nestled among sycamores and palm trees in an improbably idyllic setting. Even Vanilla Ice got in on the action, recording a nu metal album called Hard to Swallow at Indigo Ranch in 1998.

All of these artists pulled from a disparate range of influences: The brutal, yet rhythmic, down-tuned guitars of Pantera; the chugging, funk-influenced bass lines of the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Faith No More; the unhinged raps of Cypress Hill and Rage Against the Machine; the grooves and nihilism of Nine Inch Nails. When slammed together in Indigo’s cramped control room, they’d make a kind of demented sense called nu metal. Overseeing it all was a lone producer, Ross Robinson, armed with a genius for channeling youthful angst into powerful music.

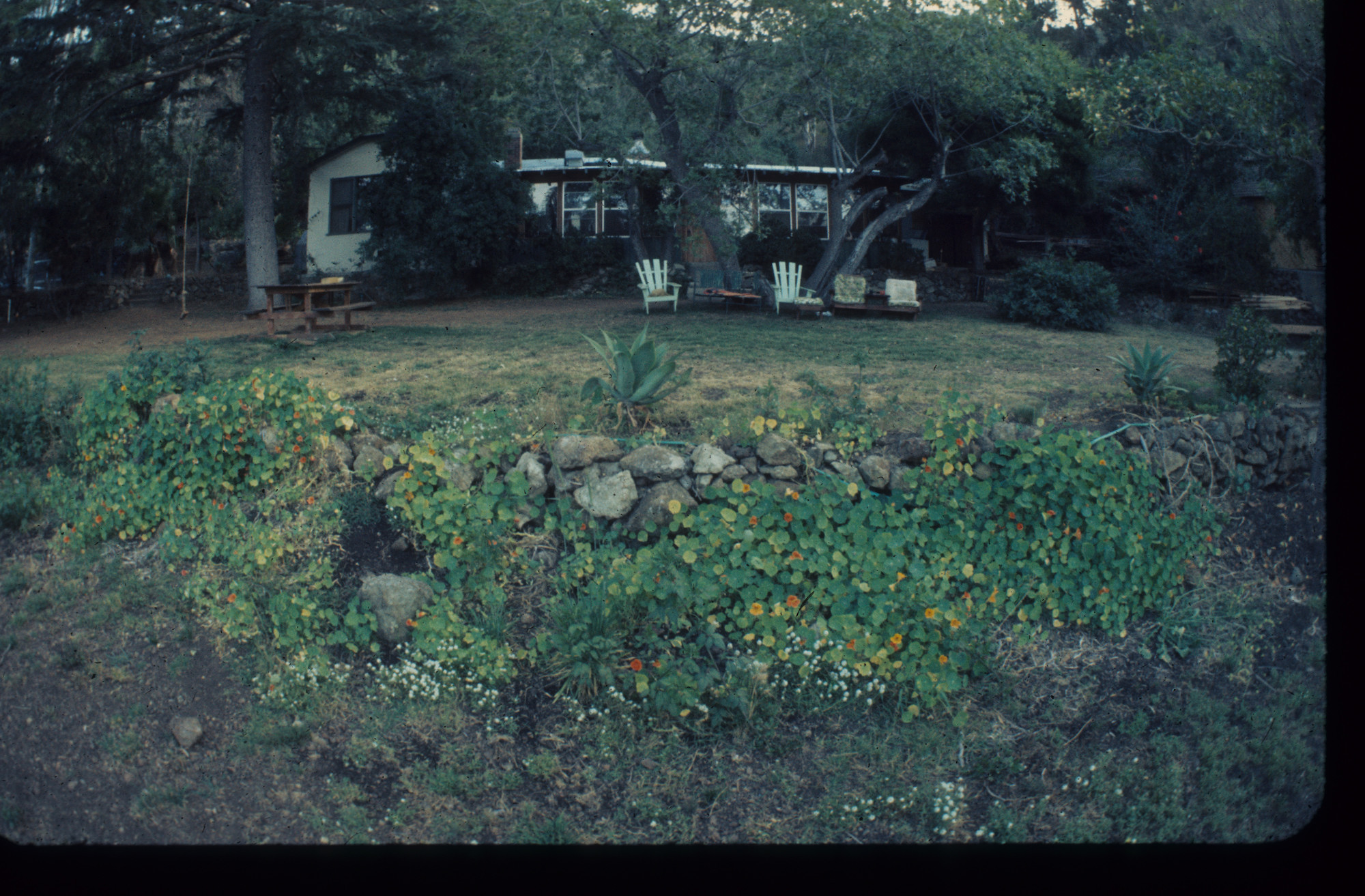

Founded in 1974, Indigo Ranch was an unlikely birthplace for nu metal. Neither its history nor its setting suggested anything as dark and claustrophobic as Korn’s primal howl of a debut, or the many turgid albums that would follow. But for six years, a 60-acre ranch in a place called Solstice Canyon, surrounded by craggy rock formations overlooking the flat blue expanse of the Pacific Ocean, reverberated with some of the harshest music ever put to tape. And then it all burned to the ground.

Indigo Ranch’s owner, Richard Kaplan, was not much of metal fan. The Indigo projects he was proudest of, according to his wife Julie, were made in the late 70s with Neil Young, Olivia Newton-John, and the aforementioned Mr. Diamond, who would later sell Kaplan his Yamaha grand piano. But Kaplan knew a good thing when he heard it. In 1994, when the members of Korn—a then-unknown band from the sun-bleached exurban sprawl of Bakersfield, 120 miles to the north—took a round piece of cardboard from a frozen pizza box, signed it, and hung it on the wall alongside the studio’s gold and platinum records as a joke, Kaplan left it up. “Don’t laugh,” he told Julie. “They’re probably gonna hit gold. They’re really good.”

“I always called them new Satanic bands—that’s what it sounded like to me,” Julie says. “I’m more of an R&B girl.”

Kaplan, who died in 2014, owned Indigo for its entire 32-year run, and was a well-liked, avuncular presence during the Ross Robinson years. With his receding hairline and bushy handlebar mustache, he resembled a younger, more jovial David Crosby. “We instantly connected,” Robinson remembers. “I just had this really great vibe with him and Julie … [like] they would see me as their kid or something.”

An engineer and avid gear collector, Kaplan bought the ranch property in 1974 and converted it into a studio, filling it with hundreds of vintage microphones, amps, and guitar pedals, many of which he had either painstakingly restored or cleverly modified. As ugly as nu metal often sounded, at Indigo, it was recorded on some of the world’s best equipment: every kind of Marshall amp ever made, dozens of microphones from Abbey Road Studios (including Paul McCartney’s favorite AKG C12 tube mic, worth about $18,000), custom-built preamps. “The translucency, the clarity on those things was insane,” says Chuck Johnson, an engineer who spent his career at Indigo, starting out there as a 17-year-old groundskeeper in 1978 and working his way up.

Korn’s debut featured several pieces of custom Kaplan equipment, including three modified Big Muff fuzz pedals that Davis remembers as being key to album’s heavy, distorted sound. “I think Ross still has them,” Davis says. “They were just raw, like circuit boards. Everything was soldered together. You had to take them and carefully plug the guitar into it, because there’s no box to hold them together.”

“Richard was the consummate collector of everything,” says Chris Brunt, who helped design the studio and worked there in its early years as an engineer. Kaplan was also a photographer, and had a huge vintage camera collection, along with a trove of guitars and jazz records. “If he had a dollar in his pocket, he’d spend two,” says Bart Johnson, an old friend of Kaplan’s who worked at Indigo as a maintenance engineer and self-described “electronics guy.”

Kaplan co-founded Indigo Ranch with Mike Pinder, keyboardist for The Moody Blues, whom he befriended while serving as the British band’s lighting director and tour photographer. At the time, the Moodys were one of the biggest bands in the world, and Pinder wanted to invest some of his “Nights in White Satin” riches in a recording studio—just not in England, where the economy was struggling and tax rates were high. Kaplan, who was originally from Burbank, encouraged him to put it in Los Angeles.

“We’d get done with the track all sweaty, and walk outside to this beautiful, flooded with light, perfect [place] where it’s hard to be all angry punk-rock,” says drummer Shannon Larkin. “It was a balance, a perfect balance.”

The site they chose was unconventional, to say the least. Tucked away at the end of a treacherous one-lane dirt road that wound for miles up into Solstice Canyon, the ranch had once belonged to the owners of the Stetson Hat Company, who used it as a hunting retreat. The main house, built in the early 1900s, “looked like a shack,” Davis says.

“It was surrounded by trees,” remembers Shannon Larkin, the current drummer for metal band Godsmack, who played drums at Indigo with Amen and Vanilla Ice. “You felt like you were out in the middle of the woods.” The local wildlife visited frequently, which wasn’t always welcome; during the recording of Slipknot’s eponymous debut album, a skunk sprayed right outside the window of the studio’s lone working shower. “Slipknot’s whole recording session just stunk,” remembers co-founder and percussionist Shawn “Clown” Crahan.

Before Kaplan came along, the home’s biggest claim to fame was that the silent movie actor John Barrymore, a Stetson family friend and notorious alcoholic, would come there to dry out before film shoots. Apparently, he was an unwilling participant in these efforts. “As we were building the studio, there were a lot of boards that were loose,” Kaplan told Tape Op in 2014, “and behind every one of them was a 50-year-old bottle of something.”

The rest of the property was gorgeous. Avocado and citrus orchards gave way to hiking trails that wound down into the canyon at the southern end of the property. A towering rock formation called Little El Capitan (and later, “Little El Kaplan,” after its new owner), flanked the ranch’s northern boundary. After the winter rains, a creek would run through the property; a hiking trail behind the house followed its path up to an 80-foot waterfall. From a bench in the orchard, you could see the Pacific. “So many amazing songs [were] written on that bench,” says Rob Agnello, who came to the ranch in the early 90s as an assistant engineer.

“It was an awesome experience being there,” Davis remembers. “Just a killer vibe. You’re in the middle of nowhere. It was beautiful. We’d just go and pick avocados off the trees.” No one seemed to find it incongruous to be making such angst-ridden music in such a beautiful setting—if anything, the ranch’s peaceful grounds provided a perfect release valve for when the bands needed a break from their own darkness. “We’d get done with the track all sweaty, and walk outside to this beautiful, flooded with light, perfect [place] where it’s hard to be all angry punk-rock,” Godsmack drummer Larkin says. “It was a balance, a perfect balance.”

The rustic setting didn’t prevent Kaplan and Pinder from transforming the house into a state-of-the-art recording studio, with a custom, 30-channel Aengus/API mixing console installed by an eccentric audio guru named Deane Jensen. Jensen, who owned a transformer company in North Hollywood, became a regular presence around the ranch, constantly fine-tuning the studio’s already-pristine acoustics.

Pinder left after just a few years, selling his share of the ranch to Kaplan and another partner, Michael Hofmann, a childhood friend of Kaplan’s who had become Indigo’s business manager. Starting around 1978, Hofmann went on a booking spree, using Indigo’s idyllic setting and top-flight gear to lure A-list clientele: Bob Dylan, The Go-Go’s, Van Morrison, Lenny Kravitz, Nick Cave, Motley Crue. Hofmann’s bookings were nothing if not eclectic; Oingo Boingo, Kenny G, and Megadeth all recorded their debut records there. By the late 80s, the studio was booked three months in advance and turning away big-name clients. “Fleetwood Mac was one them,” says Julie Kaplan, who began dating the man who would become her husband in 1986. She wishes they had turned away Sting, too: “He’s a prima donna.”

A pair of tragedies at the end of the decade hit Indigo and Richard Kaplan hard. First, in 1989, Deane Jensen, struggling with mental health issues and deep in debt, took his own life. “They found him in his office with an empty bottle of wine and a revolver in his hands,” Bill Whitlock, his business partner at Jensen Transformers, recalled in a 2014 interview. “He’d blown his brains out.” Jensen was 47.

Then, just two years later, Kaplan’s confidant and business partner Hofmann died suddenly of a brain aneurysm. Kaplan was devastated. “Michael Hofmann was one of those people you couldn’t replace,” says Chris Brunt. Hofmann was both Kaplan’s closest friend and, according to Brunt, “the person responsible for keeping the ranch together financially and aesthetically.”

Instead of hiring a new business manager, Kaplan attempted to run the studio on his own. Julie helped with the bookkeeping. But without Jensen’s equipment savvy and Hofmann’s guiding hand, over the next two years, Indigo Ranch lost most of its clients and fell into disarray.

“Richard was still wildly collecting gear,” Brunt says. “The place was filling up with this stuff. It got to the point where the control room was so crowded I wouldn’t work in there anymore. It was not friendly. It didn’t have the warmth and personality it had before.”

Into this increasingly chaotic scene stepped a 27-year-old neophyte producer from the desert town of Barstow named Ross Robinson,. Though he had gotten his start playing guitar in thrash metal bands, Robinson was clean-cut, soft-spoken, and projected an air of authority beyond his years. He had produced Korn’s 1993 demo, Neidermayer’s Mind, and helped land them a deal with Epic Records. But Epic had given Robinson a budget of just $14,000 to produce their debut album, a paltry sum in those days. Indigo Ranch was affordable—and its vintage gear was exactly what Robinson was looking for.

“The more natural it is, the better the longevity [of] whatever you record will be. It won’t be stamped in this time period or that time period,” Robinson says by phone from his home in Venice Beach. “And growing up in Barstow and being a dirtbiker and just into the outdoors, it was perfect for me.”

The drive up to Indigo Ranch was startlingly difficult. “When you first come through you’re like, ‘Where the fuck are we going?’” Davis says. “It’s the middle of nowhere.” Even after the road was paved around 1979, its hairpin turns and sheer drop-offs could be terrifying—except to Robinson, who liked to barrel up and down the mountain in his BMW 850 at top speed. “He’s an insane adrenaline junkie,” Davis says, recalling one particularly white-knuckle drive with his producer: “He just hauled ass up to Indigo Ranch, doing all those turns at 80 miles an hour. I thought we were gonna fuckin’ die.”

Robinson brought that same adrenaline-junkie energy into the studio, where he demanded 100 percent commitment from every band member, on every take. The son of a self-help guru, he treated studio time almost as a form of therapy, encouraging his bands to inhabit each song emotionally as they performed. “It’s almost like method acting,” says assistant engineer Agnello, who worked on most of Robinson’s Indigo projects.

Unlike most producers, Robinson didn’t like sitting at the mixing console and giving verbal notes after each take. Instead, “I was always in the room with the band,” Robinson says, jumping around and yelling commands and words of encouragement. If he felt like someone wasn’t playing with enough intensity, he would famously shove them, hit their instrument, or even throw whatever objects were on hand across the room at them. Robinson was particularly hard on singers and drummers. “He threw a flowerpot at Joey [Jordison],” Slipknot’s Crahan remembers of the band’s drummer during their debut album sessions. “I still have the pot.”

“People have turned my thing into silly stories of violence, or something like that, to make it sound better, but my intention was more life, more fire.”

Robinson insists that his approach came from a place of love, and wanting his musicians to deliver their best work. “The purpose was to be beautiful and absolutely on fire,” he says. “And if I felt the fire was going down I would— rrrah!” He gives a little roar, punctuated by a nervous, self-deprecating laugh. “People have turned my thing into silly stories of violence, or something like that, to make it sound better, but my intention was more life, more fire.”

Under Robinson’s guidance, the sessions for Korn’s debut album went to some pretty dark places. Davis, the band’s singer and primary lyricist, preferred to write songs that let him “yell about the horrible childhood he’d lived through,” guitarist Brian “Head” Welch wrote in his 2007 memoir, Save Me From Myself. And his bandmates encouraged him: “We all felt connected in some way because most of us shared the same sort of pain when we were kids,” Welch wrote. “The pain of being rejected, the pain of being picked on, the pain of not understanding our fathers’ love for us. Every one of us had similar issues with our dads when we were kids…It felt good to be angry and vent through our heavy music.”

Davis’ exploration of childhood trauma reached a harrowing peak on “Daddy,” the album’s closing track. Over a rumbling, menacing groove, Davis describes the experience of being sexually abused by a family friend at a young age (not his own father, he later insisted, despite the title). He repeats the song’s chorus—“I scream / No one hears me / It hurt / I’m not a liar”—until he’s audibly sobbing, gasping for breath between verses. For the track’s final three minutes, Davis is a blubbering mess, cursing and crying uncontrollably. His bandmates, playing along live in the studio, weren’t sure how to respond to their singer’s breakdown. “They were all looking back to the window at us going, ‘What should we do?’” Agnello remembers. “And we all just said, ‘Keep playing, keep playing!’”

Afterward, Davis ran from the vocal booth—you can hear the door slamming behind him at the track’s end—and disappeared down into the canyon for several hours. “We all looked at each other and every one of us was in tears,” engineer Chuck Johnson says. “It was on another level.”

By the end of the decade, nu metal’s uneasy mix of anger and anguish would metastasize into cartoonish tantrums (see: Limp Bizkit’s “Break Stuff”). But on Korn’s debut, with Davis’ elastic vocals leading the way, it was riveting. Davis was a new kind of hard rock frontman—a wiry misfit who played the bagpipes (which he recorded outside at Indigo for the opening of “Shoots and Ladders,” echoing off the canyon walls) and was relentlessly teased in high school for wearing eyeliner and listening to Duran Duran. As a singer, he proved remarkably adept at sounding both vulnerable and psychotic, wounded and defiant. “I’m not as good as you? / Fuck no, I’m better than you,” Davis snarls on “Divine,” mixing self-doubt and self-affirmation into what could have been band’s mantra (and would eventually become a genre cliche).

“He just had a way of getting in your head and really getting you inspired and wanting to do something great,” Davis says. “It wasn’t fun. But that’s how Ross rolls.”

Though in later years Davis would sometimes, only half-jokingly, call Robinson a “sadist,” he credits the producer with helping him bring so much raw emotion to his vocals. “He just had a way of getting in your head and really getting you inspired and wanting to do something great,” he says. “It wasn’t fun. But that’s how Ross rolls.”

Robinson makes no apologies for capturing Davis’ trauma on tape. “My intention was always to create a safe place, a place for him to not ever hold back,” says Robinson. “You don’t sing like that with an asshole in the room.”

Released in October of 1994, Korn’s debut didn’t change the metal world overnight. Its singles got virtually no radio play, and those publications that bothered to review it were nonplussed; the L.A. Times said the band seemed to dwell in an “insulated nightmare universe” in which it “slam[med] its collective head repeatedly against doors it can’t even see.” But people in the industry took notice of the album’s unique, pummeling mix of groove metal, grunge, and hip-hop, and wanted to know who was behind it.

One of the first bands whose attention it caught was Sepultura, a Brazilian thrash metal band who had already begun gravitating towards a more groove-oriented style. After hearing Korn and another rising act in early nu metal, Deftones, “we started using lower tunings,” says Sepultura guitarist Andreas Kisser, “going for groove—more groovier parts instead of fast death metal parts.”

Recorded with Robinson at Indigo Ranch in late 1995, Sepultura’s sixth album Roots did much to legitimize the budding nu metal scene. Though the album’s relative lack of technical shredding appalled some metal purists, its mix of heavy riffs and Brazilian folk instrumentation gave it an arty, experimental feel that won over many skeptics. Like Korn’s debut, it was thrillingly heavy, with bass lines and kick drums that tugged at the mix like the powerful undertows swirling off the Malibu coast.

“Ross was always adamant,” Agnello says. “That kick drum always had to be forward.” As they mixed everything down to half-inch tape, adds engineer Chuck Johnson, “we added bottom to it. Me coming from my jazz background, I didn’t know about metal. I just wanted it to sound big. I was used to doing R&B where the bass was there, so I pushed the bass and made it pump.”

As nu metal’s popularity grew, with Korn appearing on metal magazine covers and opening for Ozzy Osbourne (who was on hand when the band received their first gold record, fulfilling Kaplan’s prophecy), Robinson kept the Indigo Ranch crew busy. He produced albums for Manhole (featuring Tairrie B, once the first female rapper signed to Eazy-E’s Ruthless Records), Cold, Human Waste Project, and Soulfly, the new band from ex-Sepultura frontman Max Cavalera. He also managed to squeeze in Korn’s sophomore album, Life Is Peachy, and the debut album from a Florida rap-rock band called Limp Bizkit. All this took place at Indigo Ranch in the span of just two years.

By mid-1998, the breakneck pace at Indigo was running everyone ragged. Robinson was booked to produce four albums—by Vanilla Ice, Amen, Slipknot, and Machine Head—back-to-back the latter three through Roadrunner Records, an independent that was rushing to cash in on the nu metal craze. But the sessions were running long and overlapping, forcing the engineers to work around the clock. “I would be sleeping underneath the console or in the control room,” Johnson remembers. Amen’s lead singer, Casey Chaos, had also been hired to work on the Vanilla Ice album, Hard to Swallow, and wound up living at the ranch for six months, much of which he spent sleeping in an unused isolation booth. “I was going insane,” he says. “Like Shining type shit…just covered the walls with blood and shit and scraps of paper.” Kaplan stepped in to help, setting up and breaking down mics and drum kits, essentially performing as an uncredited second engineer. “I’m not a guy who grabs for credits,” he said in his 2014 Tape Op interview. “I probably should have, but I didn’t.”

“I was going insane,” Casey Chaos says. “Like Shining type shit … just covered the walls with blood and shit and scraps of paper.”

It didn’t help that nearly everyone at the ranch was getting high—with the notable exception of Robinson, a health fanatic whose substance of choice was wheatgrass shots. Bands had been following in John Barrymore’s shambling footsteps at Indigo since the beginning; booze and weed were omnipresent, and both Welch and Davis admitted to doing meth while recording Korn’s debut. During 1998’s marathon sessions, “we all did drugs and drank—no secret,” Amen drummer Shannon Larkin says.

Even the staff at Indigo “did a lot of partying,” Agnello admits—including the boss, Kaplan, who would eventually join Alcoholics Anonymous. While the studio team prided itself on its work ethic, the long hours blurred the lines between business and pleasure. “We’d take a break and I would go run off to the bathroom and do a line,” Johnson says. “We always kept it together. But we weren’t angels.”

Despite the drug use and the scheduling headaches, “everybody did what they should,” Slipknot’s Crahan says. “Everybody made great art. Everybody got out alive. We all did what we had to do. But I always hated the label for doing that to all of us.”

From a sheer technical standpoint, Slipknot’s self-titled debut album may be Ross Robinson’s greatest achievement. The masked nine-piece band from Iowa had two guitarists, three percussionists, a turntablist, and a sampler/keyboardist. Wrangling all those parts into one frenetic whole was a huge challenge—especially the layers of drums, all recorded without click tracks, and manually spliced together on two-inch tape. “We had tape everywhere,” Agnello recalls. “On the floor. Draped over the machines.”

Released in the summer of 1999, Slipknot represented a high-water mark for nu metal. It became the fastest selling metal debut in history, eventually going double platinum, and achieved new levels of harshness and aggression in its dense layers of percussion, guitars, and electronics. But it was also the beginning of the end of nu metal’s reign at Indigo Ranch.

Robinson’s last two projects at Indigo, from post-hardcore bands Glassjaw and At the Drive-In, were complete departures from nu metal. (So, for that matter, was Amen’s 1999 self-titled LP, a blast of Black Flag-style hardcore fury that, because it was produced by Robinson and released on the heels of Slipknot’s debut, was lumped in with nu metal. “It was the most heartbreaking thing,” says Chaos, who still blames the record’s poor US sales on how it was mislabeled by the press.) By 2000, Robinson occasionally referred to Glassjaw’s brittle, rhythmically shapeshifting Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Silence as his attempt to “destroy Adidas rock”—a pointed reference to Korn, who favored Adidas tracksuits in its early days, and its Life Is Peachy single, “A.D.I.D.A.S.” With its puerile chorus, “All I day I dream about fucking,” the song became an unintended template for nu metal’s transmogrification into a new kind of frat-rock, with a fan base probably would’ve beaten up Davis in his eyeliner-wearing days.

“It was separate from the rest of the world,” Robinson says of the albums he recorded at Indigo Ranch. “And then there were bands that would take the formula, and it didn’t feel authentic.”

By 2001, as bands like Linkin Park and Incubus were grafting elements of nu metal onto mainstream, radio-friendly rock, Robinson had moved onto other studios and other genres. He produced albums for The Cure and Tech N9ne, and worked with new bands he was finding on MySpace. He returned occasionally to nu metal, but never at Indigo.

“I think drugs were a heavy deal up there,” he says when asked why he stopped working at the ranch. “And it was so over my head I didn’t see it [at first].” But towards the end, it began affecting the quality of his work. The studio’s once-pristine equipment was falling into disrepair; engineers like Johnson, once the best in the business, were strung out and off their game. “I couldn’t make a rough mix and send it out without it being messed up,” Robinson says. To this day, he sounds regretful at how his time at Indigo ended: “It’s pretty heartbreaking.”

Robinson’s relationship with the genre he helped birth remains complicated. In 2016, he tweeted, “I don’t do bands that copy Korn. That style is a rotting corpse of my past.” Speaking by phone on a recent August morning, he’s more circumspect. “To me it was separate” from nu metal, he says of the albums he recorded at Indigo Ranch. “It was separate from the rest of the world. And then there were bands that would take the formula, and it didn’t feel authentic.” That extended to acts he was working with—though he declines to name names—who Robinson says were “turning into, you know, a Mötley Crüe sort of lifestyle—”Girls, Girls, Girls”—when it was completely something else when we started.” He laughs his nervous laugh again. “But yeah, I’m proud of all of it.”

Without its best customer, Indigo Ranch languished. The early 2000s were tough on old-school, analog studios, and on the music industry in general. “I think this iTunes thing put us out of business,” Kaplan’s widow Julie says. “Everybody was downloading, so he wasn’t getting his royalty checks.”

Richard Kaplan died of leukemia in November 2014 at the age of 68. Eight years earlier, he had sold off Indigo Ranch for $2.85 million to a couple of “trust fund babies,” in Julie’s words. “The ranch was really becoming a millstone,” says studio designer and engineer Chris Brunt, who kept in touch with his former boss right up until his death.

Less than a year after Kaplan handed over Indigo Ranch’s keys to its new owners, the Corral Fire swept through the top of Solstice Canyon, destroying everything in its path. By then, all of Kaplan’s old gear had been removed—except for Neil Diamond’s grand piano, which the new owners had purchased.

“The land was cleansed,” Rob Agnello says of the fire that wiped out Indigo Ranch Studios for good. He notes that Solstice Canyon was named for the winter and summer solstice ceremonies performed with music there by the local Chumash Indians, centuries before the Stetsons or Kaplan and Pinder showed up. “So I always felt it came out of the land, the music up there.” The era of Indigo Ranch, Agnello believes, “was just a time that was meant to be.”

Julie Kaplan remembers the exact day her husband got sober: April 1, 1999, not long after the grueling sessions with Amen, Slipknot and Machine Head. The Malibu chapter of Alcoholics Anonymous, where Richard Kaplan later served as treasurer, commemorated the anniversary earlier this year. “He would have had 19 years clean and sober,” Julie says proudly.

Over the last 15 years of his life, Kaplan became a beloved figure in the Malibu AA community, sponsoring many other alcoholics in their quest to stay sober. “He became very instrumental in helping a hell of a lot of people,” Chris Brunt says. At his memorial service, “Ninety percent of the people there had nothing to do with the music industry. They were people he’d helped.”

“He liked to party a little bit, but who didn’t?” Davis says. “We were in rock ’n’ roll.”

Many of the musicians and engineers who passed through Indigo Ranch cleaned up their acts, as well. Chuck Johnson left the ranch around the same time Robinson did and got sober in 2004. After a stint in rehab and joining AA, Larkin got on the wagon in early 2016. “We all went through shit,” says Korn’s Davis, whose entire band is now clean. “I got sober first. I’m coming up on my 20 [years] next month.” (After Davis was interviewed for this article, his estranged second wife, Deven Davis, died on Aug. 17 of unspecified causes. On Aug. 23, Jonathan released a statement about her death in which he said, “She had a very serious mental illness and her addiction was a side effect.”)

One of Kaplan’s final acts, before he passed, was to bequeath the name Indigo Ranch to the Beach House Treatment Centers, a group of sober living facilities in Malibu. The new Indigo Ranch, located ten miles down the coast from the original, is a Tudor-style house set on seven acres with a swimming pool and tennis courts—and a recording studio, accessible only to the facility’s residents. “We feel we can connect with the clients through the music,” says co-founder Charlie Bentz, who became close with Kaplan though AA.

Davis, who lost touch with Kaplan over the years, is pleased to learn about his legacy. “That’s cool. I’m glad he got sober. That’s good. He liked to party a little bit, but who didn’t? We were in rock ’n’ roll.”

Andy Hermann is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter.