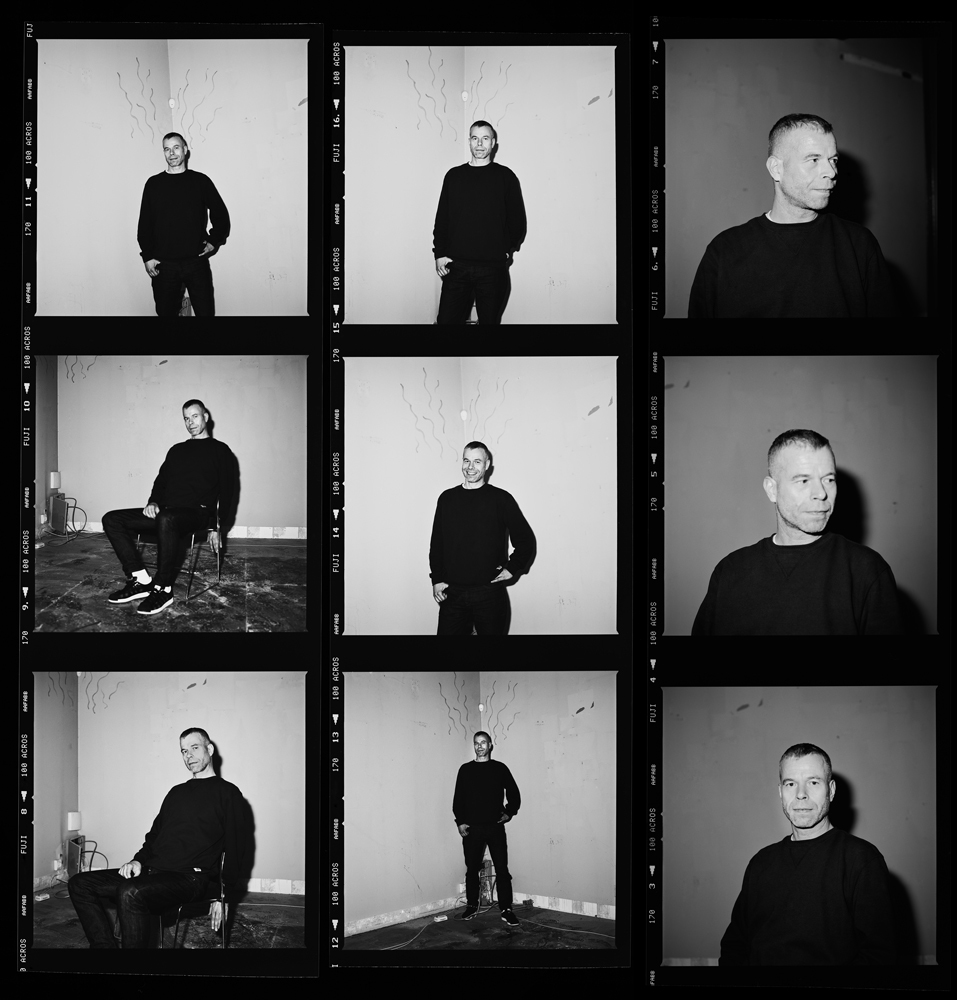

“I don’t actually know how to play,” Wolfgang Tillmans admits to me as he sheepishly half-pokes at the keys of a vintage synthesizer. We’re at my friend’s loft and music studio on the west side of Toronto, and I’ve just presented the celebrated German photographer with a wall of drum machines and analog synths to mess around with.

Videos by VICE

Even though it looked like the impromptu set I had selfishly hoped to orchestrate wasn’t going as planned, I knew enough about the man to bank that’d he’d be stoked to hang out in the space and nerd out on gear. After all, not only had he recently released a techno EP Device Control (the title track of which was featured on Frank Ocean’s Endless) but more importantly, he had spent the formative years of his art career documenting the scenes built around the sounds that came from these machines.

From his early work covering the late 80s acid house movement in Europe, to his recent series on the now-defunct LGBTQ community/art/dance space Spectrum in Brooklyn, capturing nightlife has been a recurring thread in his work over the last two decades. But this isn’t “party photography” in the same disposable snapshot sense that plagued blogs during the early 2000s birth of EDM. His portraits of club goers are intimate, fragile, and show clubs as spaces of unbridled freedom and—as I was to learn from our conversation—struggle. A struggle that now, in the face of a political mindset that’s seemingly ever-closing, is more important than ever.

While in Toronto for a talk presented by Canadian Art, I sat down with Tillmans to talk about music, art, politics, and how his work intersects all of these areas.

THUMP: A lot is made of your beginnings in the late 80s, early 90s, immersing yourself in rave culture and the acid house scene. What was it like to be a part of that and how did it affect your art?

Wolfgang Tillmans: Even though the music is still with us, one mustn’t forget how different the world was back then. It was not totally okay to be gay or lesbian. It was in many ways a less open place because of the 80s coming to a close, the conservatism of the West being questioned, and of course, the collapse of Eastern Bloc communism. There was really an unprecedented questioning of all types of values. It’s a little bit unfair to portray that always as this golden age, because today there’s just as much at question and at play.

Today there’s all sorts of openness available. I just feel like people should be a little bit more aware and appreciative that they have this opportunity of expression, and have to push back at the same time against the encroaching and closing down of urban spaces. In one way, I feel a continuity from back then and on the other hand, the reason people are so interested in the 90s comes from a spirit that we should look at and see what that can tell us.

When they see an asshole act out his fantasies, act out his egotism, his misogyny, they think ‘Right I like that guy, because I want to be like that.’ That is why people like Putin and Trump are so successful and not only with men, but actually with some of the female population.

Do you see things like Brexit and the election of Donald Trump to be a movement away from that openness to internationalism?

Well, this emerging right wing populism isn’t proving the last 25 years wrong. That would be a terrible misinterpretation of the situation. The reason we have these nationalist ideas is because of 60 years of social progress, women’s rights, racial integration, and LGBTQ rights has made a better society for many. I think that’s made the white male feel insecure and threatened. This is a story of many people’s successes making a more open world and lifting millions of people in other countries, formally developing countries, into middle classes that is somehow threatening the unique world domination of the white male.

We’re experiencing a backlash from them, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t fight them full on and hold the line, because it’s not that people celebrating diversity have done anything against the white working classes. It’s a strange hijacking of the white male, supposedly working class, when in fact it’s actually white males who have voted majority for Brexit and for Trump. It’s a hijacking of this populist by right wing billionaires. It’s so bizarre that you have right-wing rich people buddying up with working class people telling them they act in their interest. I think we have to stop bowing to that and really say yes we believe in this and we have the right idea.

I think to me it did feel like an outlash, or what they’re a calling a “whitelash,” against this new world or this idea of America that they feel they’re losing control over.

It has a lot to do with sex and I think we need to talk a lot more about sexuality and politics. A lot of the people would’ve thought that the “grab them by the p” quote from Trump finished his candidacy, when in fact it was a great promotion of it. In the end, a lot of people are assholes. I did this text piece for this month’s issue for ArtForum that circles around the phrase “inhibit assholes.” They may be on the left, the right, they may be gay, they may be straight. It’s unfortunately the case that a majority of people maybe aren’t peace-loving, wonderful, idealistic people. When they see an asshole act out his fantasies, act out his egotism, his misogyny, they think “Right I like that guy, because I want to be like that.” That is why people like Putin and Trump are so successful and not only with men, but actually with some of the female population.

I know you were very outspoken against Brexit. Were you surprised that Trump was elected?

No. Having lived most of my life in Britain and following the tactics of Rupert Murdoch’s press and general right wing press over there, I know how relentless they maneuver and manipulate the public. I felt the combination of an unloved candidate; in Brexit’s case, the unloved European union, and in the American case, the unloved but liberal Hillary Clinton, with that passionate media machine and white, xenophobic rage, it’s an unbalanced brew. When there’s no love on the side and a lot of hate pushing, how can that balance? When I arrived in New York the day after Brexit, the New York Post, the Murdoch paper had this cover of two fists, one painted in US colours and one in Union Jack colours, and the people were rising. When you think of the absurdity of Murdoch, this billionaire, giving like a communist, I posted on Instagram, “I’m gonna see it happen again.” I always expected this could very much happen.

How do we counterbalance that or change peoples’ minds?

It’s more a matter of stopping people from getting infected with this polarized virus. I do believe once you’re polarized, it’s very difficult to get you out of that. Whether it be a religious climate change denial, religious fundamentalism, or a quasi-religious racism, once that’s in your brain, it’s very difficult to get out. The truly shocking thing is that 46% voted for a white supremacist-supported guy in America. My hope is that a lot of European countries can be stopped from drifting towards that vote, but it’s an uphill struggle. We should not be pulling ourselves down with the all the bad news. Always remember it’s our success, our progress. That’s not a selfish, urban interest. The freedoms that have been found and fought for in the last decade can be enjoyed by many and they’re not just for a few. That’s why I always think that partying, celebration, music, and political activism are all part of the same coin.

Why photographer Wolfgang Tillmans wasn’t surprised by the rise of Trump: https://t.co/0blXYdvruY pic.twitter.com/RxJhc7Qe8Y

— VICE Canada (@vicecanada) November 30, 2016

So approaching that not in such a intense, dogmatic, depressive way, but focusing more on the positive?

Yes. There are obviously economic challenges, but by and large, it’s only fear we have to fear. Once people are infected with fear, there’s little room to maneuver. I think it’s important to understand that the world is actually a much better place today in many, many ways. We should take heart and we should take pride in that and defend it.

You’re here in Toronto to talk about your book What’s Wrong with Redistribution?, which deals with the idea of truth. Did you learn anything about truth from these recent events?

I began a new project in my exhibition-making in 2005 called Truth Study Center, which comprised of varying amounts of tables that contained a number of conflicting “isms” I saw rise in despair and shock in the early 2000s. Stuff like fundamentalism, creationism, islamism, HIV/AIDS denial, all sorts of crazy thoughts that were usually propagated by men. I called this “Truth Study Center” kind of tongue-in-cheek because it was a more a display of all this insanity going on.

Now 11 years later, I see myself actually studying concepts of truth. It’s no longer about showing the madness going on, for me in it’s latest incarnation in Los Angeles at Regen Projects, the Truth Center installation there deals with questions of neurologic science, how the brain works, and why can’t we change our mind when faced with facts. Honestly, I find that’s the most urgent thing I see our world faced with. We’re shrugging at irony and rolling our eyeballs at post-truth, but I feel we are on the most dangerous path at the moment, the consequences are very real.

All these conspiracy-type things you’ve gathered 11 years ago are now becoming a reality in a sense that there are real consequences to believing those things. I think that does really underline the importance of trying to figure that out.

I think there has to be a certain moral code which we should adhere to. I’ve had trouble with a lot of organized religion. Even though my initial experience has been a good one with Protestant Christianity, in the end I found Quakerism the only appealing religion, because it’s foundation is to say that men can tell other men what God thinks. The other fundamental principal is to not lie, which really got them into trouble in Britain 300 years ago, which is why so many left and moved to America. It’s an incredibly principal belief and group of people. I think there’s nothing better than good governance, the rule of law, and when people tell the truth. It’s not boring or uptight. These are the radical ideas to help you stay in the center and tell the truth.

Do you try to mold your life in the Quaker style?

I don’t in terms of lifestyle, but I think the sense of humility has stayed with me and a sense of duty. It doesn’t exclude having or enjoying the contradictions of life because life is contradictory. To claim there’s only one way or the other way is untrue.

How do the themes you explore on your EP Device Control tie into your greater work?

I guess in both my visual work and music there are different aspects at play the same time, it’s not diluting it, I think it makes it stronger. On one hand there’s “Device Control,” which is a semi-serious, semi-tongue-in-cheek observation of contemporary life and a slight mocking of the practice of constant self-streaming. Then there’s a much more serious, spoken-word piece called “Angered Son,” which is about the Orlando shooter and his father, who said in a newspaper quote that his son “felt angered by recently having seen two men kissing.”

There’s an approach of sampling machine sounds and using another quote from a previous piece of mine that goes “What we do here is a crime in most countries. But it’s not. There is no victim. Leave us alone.” I really like that thought, because people constantly see nightlife as a danger, a nuisance, illegal and as something that needs to be curbed. We’re living in a democracy and these are adult people that want to have a space of freedom for a few hours. I stand by the belief that the freedoms that have been fought for and that we enjoy in a free society since the French Revolution, they have been fought for by people against forces like the church, or the aristocracy, or the super rich, or the slave drivers.

Those things have been fought for and have to be defended, but actually have to be enjoyed, because if you don’t enjoy then you don’t know what you’re defending. That’s where my music is located at, experimentation, and a certain photographic approach to sound. I recorded a gong and a triangle, where I moved the microphone ever closer to a lower-sounding gong, and that’s kind of like a photography of the sound. I used a cassette recording from 30 years age when I was 17 and I last made music. I used the simple cassette recording and thought “Okay this is the negative, this is all I have,” and then went into the studio with an engineer. He then replayed everything he can hear and laid it under the original filtered recording.

Would you say the process is just as important as the outcome and the sound sources?

Yes. I never wanted to do “art music,” I wanted to work with music in a larger context. It doesn’t have to be on the charts, but it’s not about just following the process no matter what it sounds like. This summer I’ve been playing, writing, and recording with other live musicians under the name Fragile, which is the project name I chose over 30 years ago. That resulted in six very different songs I put out in December as an EP under the name Fragile. I like that “Device Control” is like a dance track, it ended up on Frank Ocean’s Endless.

Talk to me about that, I heard you took him to Berghain and you guys partied. What was it like working with him?

It wasn’t a long-term planned collaboration and we’ve been in touch very sporadically. I always felt for all the difficulty he brought to different stages of the photography, I’ve always thought he’s an extremely good artist and we see things eye-to-eye. Then he thought this piece of music of mine was interesting enough to have on his album, which I think is pretty amazing. I couldn’t have asked for a better peer endorsement, but I had no idea when exactly it would come out and how much of it would come out. In the end, he decided not to just use a 20 second intro, but he put the whole 7 minute song on the album. I was just as surprised to find out as everybody else.

I know SALEM did a remix for you, do you have any other plans to work with them?

I just saw them in LA, but no, they’re focusing on getting their album ready. In terms of other collaborations, there’s this really exciting project that’ll happen at the Tate Modern in this 30-metre old oil tank. During my four month exhibition next spring, I’ll have this tank for ten days to do an ongoing music experimental installation and I’ll collaborate with a whole range of musicians on that.

Any collaborations you can talk about?

To be honest, it really shouldn’t be about names. I feel like even there were big ones they wouldn’t be appearing in some sort of big feature, but there certainly won’t be any Frank Oceans involved.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Check out more of Wolfgang Tillmans’ work on his official website.

More

From VICE

-

Gonin/Getty Images -

Illustration by Reesa. -

Screenshots: Sega, Nintendo, Square Enix -

Screenshot: Team17