“Drug overdoses are taboo, so it’s hard to get people to understand that users don’t just live in poor neighborhoods in big cities,” says Danish social entrepreneur and activist Michael Lodberg Olsen. “It could be your son or your daughter—so you better learn what to do in an overdose situation.”

Though Olsen is based in Copenhagen, his statement rings grimly true in a global context. For the first time in history, opioids are killing more people than guns in the US. 2015 saw about 33,000 Americans die from opioid-induced overdoses due to the use of heroin and prescription painkillers skyrocketing over the past few years. The US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) has declared a national opioid epidemic, and even Trump’s paying attention: he recently announced the launch of a task force to fight opioid addiction in America.

Videos by VICE

Women are increasingly at risk, too. According to Harvard Medical School, women tend to become dependent on drugs faster than men and are more susceptible to relapse. And while men are more likely to die of an overdose of prescription painkillers, the female mortality rate has dramatically increased by 400 percent between 1999 and 2010, compared to just 265 percent for men.

Drug overdose rates are rapidly growing in Denmark, too, which is why Olsen founded Antidote in 2013. Its network of volunteers, medical professionals, and users runs free, two-hour courses teaching people to administer first aid for opioid-induced overdoses. I decided to do the course in Copenhagen to see what it would take to potentially stop an overdose—and found that the process is surprisingly easier than one may think.

Read more: What Happened When We Tested Women’s Drugs at a Music Festival

“If users are at the course, we’ll often ask them how they take care of themselves while doing drugs. They’re the experts, really,” says Dr. Mikkel Elvekjaer, one of Antidote’s volunteer physicians and my course instructor for the evening. The nationwide and primarily volunteer-run organization welcomes everyone to their courses—from health professionals and police officers to drug users and their family members.

Elvekjaer begins our session by clearing up a prevalent misconception about overdoses. “Our government does so many things to make sure roads are safe, but not overdose victims—and that’s just talking about the fatal ones,” he tells me. “There are many more non-fatal episodes with serious consequences.”

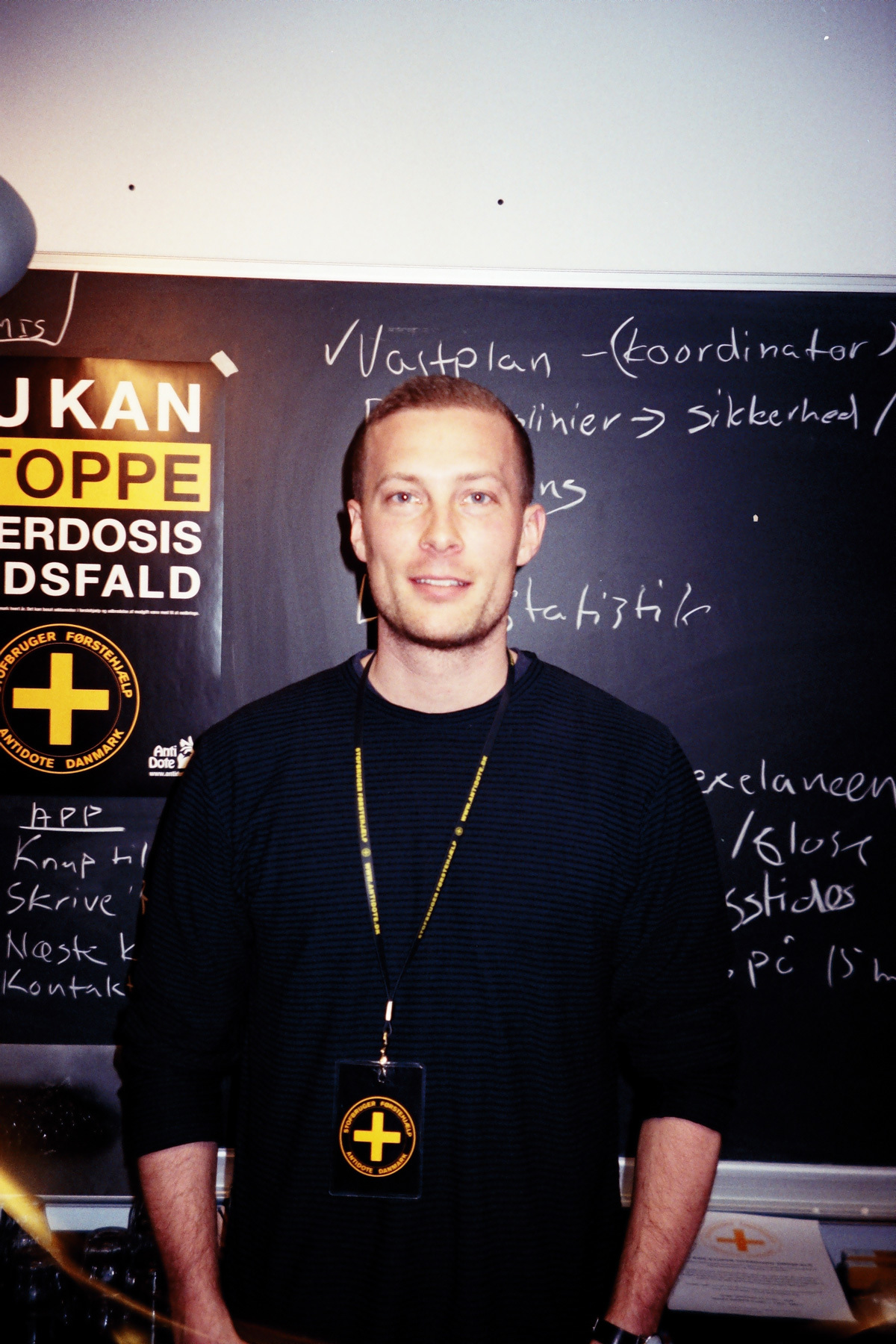

Dr. Mikkel Elvekjaer, one of Antidote’s volunteer physicians.

Although data on non-fatal overdoses is lacking, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction estimates that for every fatal overdose, 20 to 25 non-fatal episodes occur—and that 50 to 60 percent of all drug users have experienced an overdose. While fatal overdoses get much more media coverage, non-fatal episodes bear serious health consequences, resulting in issues like cognitive impairment or renal failure and increasing the risk of another OD in the next year.

“As a society, if we know we can cut down mortality rates, it’s our responsibility to do as much as possible,” muses Olsen. “And Antidote’s model is so cheap and easily replicable.”

The cheapness comes from its simplicity. The course basically involves training people to administer CPR and the opioid antidote, naloxone, from kits that cost about $20-40 each. A medicine originally used in hospitals to restore patient respiration post-surgery, naloxone has since been used as a rapidly effective opioid antagonist: It attaches to the receptors in the body that are affected by opioids and blocks the drugs from working, which restores an overdose victim’s breathing.

The naloxone kit provided by Antidote.

“People often ask me about the consequences of giving naloxone to somebody who actually isn’t overdosing,” Elvekjaer says, pulling out a typical naloxone kit consisting of a syringe, two vials of naloxone, and a rescue breathing mask. According to him, overdose symptoms like blue lips and nails, unconsciousness, pinpoint pupils, and breathing problems are relatively non-specific, which can make it difficult to determine whether an overdose is opioid-induced or not.

However, he notes that if you suspect it, you should administer naloxone anyway—because even if you’re wrong, the antidote won’t worsen the situation. “The great thing about naloxone is that it’s non-toxic—so if you were to give it to me now, for example, I wouldn’t feel anything.”

Naloxone’s non-toxic nature makes it the only safe opoid antidote out there, and is also partially responsible for its uniquely wide distribution in the US. While legislation in Europe around naloxone can vary dramatically—for example, Denmark allows third-party prescriptions and has implemented free distribution programs, yet neighboring Sweden’s zero-tolerance drug policy overwhelmingly limits naloxone access to medical personnel only—the HHS and the FDA are both working to increase naloxone access.

The training process.

Although federal law defines naloxone as a prescription drug, states have the power to determine how prescriptions are issued; as a result, 47 states passed legislation to make naloxone more accessible through methods like free community distribution programs and online naloxone locators, and 42 of those states sell it over the counter.

That accessibility strategy is working: Naloxone reversed almost 27,000 opioid overdoses over 18 years—and between 2013 and 2015, naloxone dispensing from US retail pharmacies has increased by more than 1,170 percent.

As Elvekjaer explains how to prepare a syringe with naloxone, he also excitedly shows me a nasal spray. Naloxone is currently distributed in Denmark via syringes, but the country is implementing pilot nasal naloxone spray programmes. “Distributing naloxone via syringe can be pretty stressful to manage in a chaotic overdose situation,” he explains. “This nasal device is a big step towards making overdose prevention more effective.”

The CPR dummy.

The nasal spray hit the American market in 2015 to positive results: A study in the Academic Journal Pain and Therapy found that while only two-thirds of respondents were successful in administering naloxone via syringe, all respondents were able to correctly use naloxone via nasal spray. “Especially since opioids with greater potency like fentanyl are becoming more of a problem, the nasal device will let you act faster in an overdose situation,” Elvekjaer adds.

When Elvekjaer moves on to the training process, he has me administer CPR to a dummy and show him how I’d load a syringe with naloxone. The whole process takes about ten minutes, which proves why training programs such as Antidote are so necessary, especially in the face of an opioid epidemic. As long as you know basic CPR and have access to naloxone, practically anyone can potentially stop an overdose—if you stick around to make sure the antidote works and remember to call for help, that is. “Naloxone is often shorter-acting than some potent opioids,” Elvekjaer notes. “If you just walk away after administering naloxone, it may wear off while the opioid reappears and brings back the overdose.”

For More Stories Like This, Sign Up for Our Newsletter

As my course finishes, Olsen tells me what drove him to start Antidote in the first place. “Getting users, family members, professionals and all sorts of people in a room together creates a rare and open dialogue,” he says. “Suddenly, it’s not a typically judgmental thing where we’re talking down to drug users: We work though the danger of the situation together.”

Courses like Antidote don’t just equip people with the tools they need to prevent deaths; they also break social taboos around drug use in the process. “That empowerment is so important,” Olsen remarks as we leave the Antidote office. “To me, acknowledging each other without judgment like that is the first step towards creating meaningful change.”

All photos by Ágúst Einar.