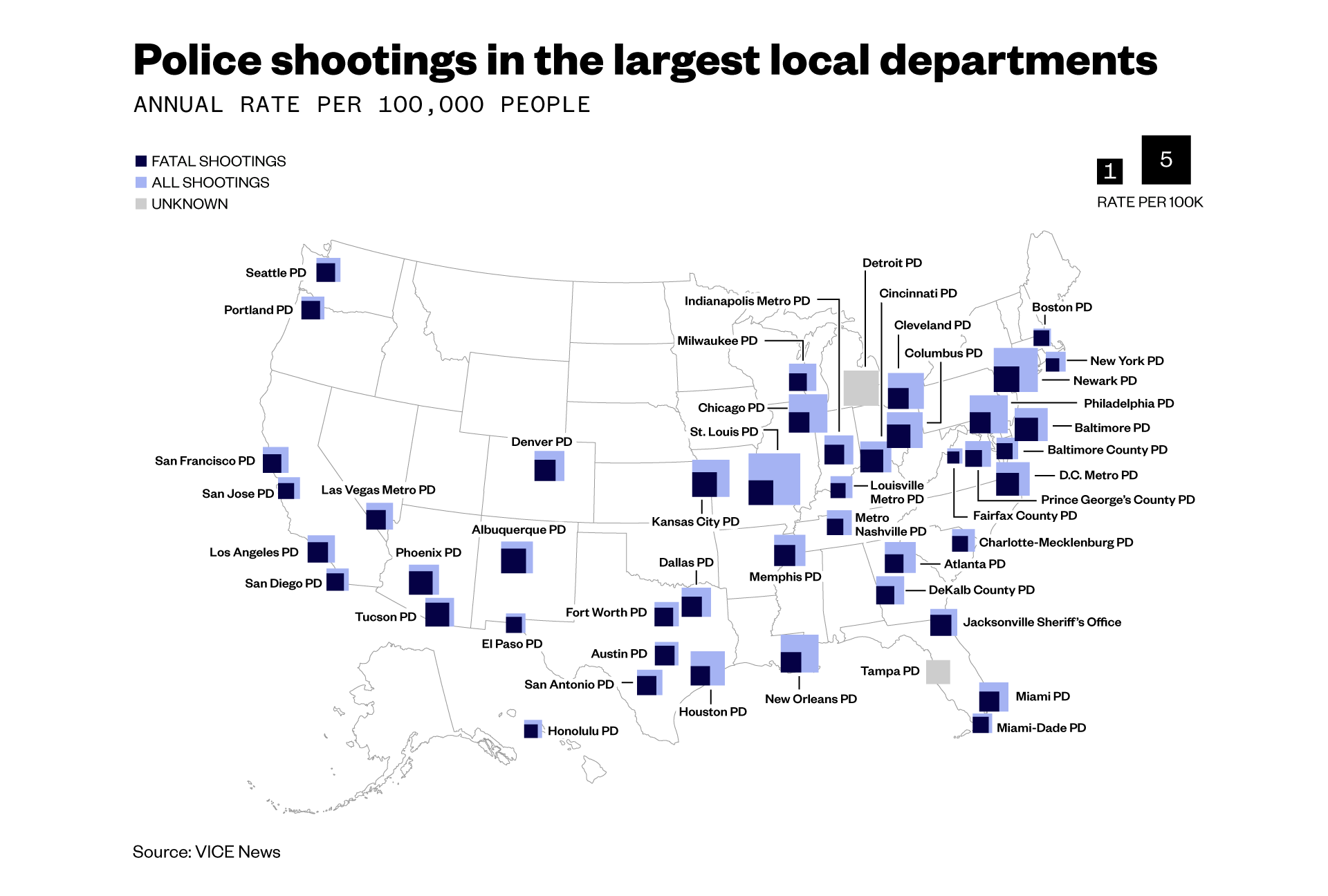

An exclusive analysis of data from the 50 largest local police departments in the United States shows that police shoot Americans more than twice as often as previously known.

Police shootings aren’t just undercounted — police in these departments shoot black people at a higher rate and shoot unarmed people far more often than any data has shown. Recent reform efforts have already worked to bring down police shootings, our investigation shows. Yet Attorney General Jeff Sessions is moving away from these reforms, to the dismay of advocates, experts, and some local law enforcement officials.

Videos by VICE

VICE News examined both fatal and nonfatal incidents to determine that cops in the 50 largest local departments shot at least 3,649 people from 2010 through 2016. That’s more than 500 people a year. On more than 700 other occasions, police fired at citizens and missed. Two-thirds of the people cops fired at survived.

In Los Angeles, an officer shot a 13-year-old boy playing with a replica gun, leaving him paralyzed. In Philadelphia, an off-duty cop shot his own son. Officers in Baltimore killed an off-duty colleague and struck three women with errant bullets while responding to a fight outside a nightclub. A cop in Seattle accidentally shot a teenage girl in the leg while drawing his gun; the teen was promptly arrested and jailed on an outstanding warrant.

Police shootings on the whole are rare, but experts say nonfatal shootings are just as important to understanding police violence as fatal encounters are.

“We should know about how often it happens, if for no other reason than to simply understand the phenomenon,” said David Klinger, a former Los Angeles police officer and a professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. “How often is it that police are putting bullets in people’s bodies or trying to put bullets in people’s bodies?”

After the 2014 killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and other high-profile cases where police shot and killed unarmed black men, the Washington Post and the Guardian began keeping a running tally of fatal incidents. Then-FBI Director James Comey called the lack of federal data on police killings “embarrassing” and committed the agency to a new initiative to collect statistics from police departments. A handful of state and local agencies also made their data public. The Tampa Bay Times and the Texas Tribune counted all police shootings in Florida and the major cities in Texas.

But just 35 police departments participate in the federal initiative today, out of 18,000 U.S. law enforcement agencies. And as VICE News found, some departments don’t have systems in place to track nonfatal shootings by their own officers. Others wouldn’t provide data on demographics or whether the people they shoot are armed, making it hard to judge why and how often cops use deadly force or the efficacy of reforms.

Until now, there has never been a national reckoning of police shootings that includes Americans who are shot by cops and survive.

VICE News’ investigation is the first attempt to count both fatal and nonfatal shootings by American police in departments across the country. The data isn’t comprehensive — it covers about 148,000 police officers who serve more than 54 million Americans — but it offers the most complete picture yet of when cops shoot and who they shoot. The national tally of police shootings beyond our data is likely far higher.

Kelvion Walker was an unwitting passenger in a stolen vehicle when he was shot in the stomach by a Dallas police officer. The bullet is still lodged in his body, and he suffers from lingering pain and digestive problems. He’s suing for $10 million.

VICE News sought records on officer-involved shootings from the country’s 50 largest local police departments; 47 responded with data sufficient for analysis. Many fought hard to keep the information secret, and some responded to our requests only under threat of legal action. One department sent a CD-ROM containing a single spreadsheet file through the mail. Another wanted to charge us thousands of dollars unless the records were inspected in person.

In all, our data set includes information on 4,117 incidents and 4,400 subjects over seven years.

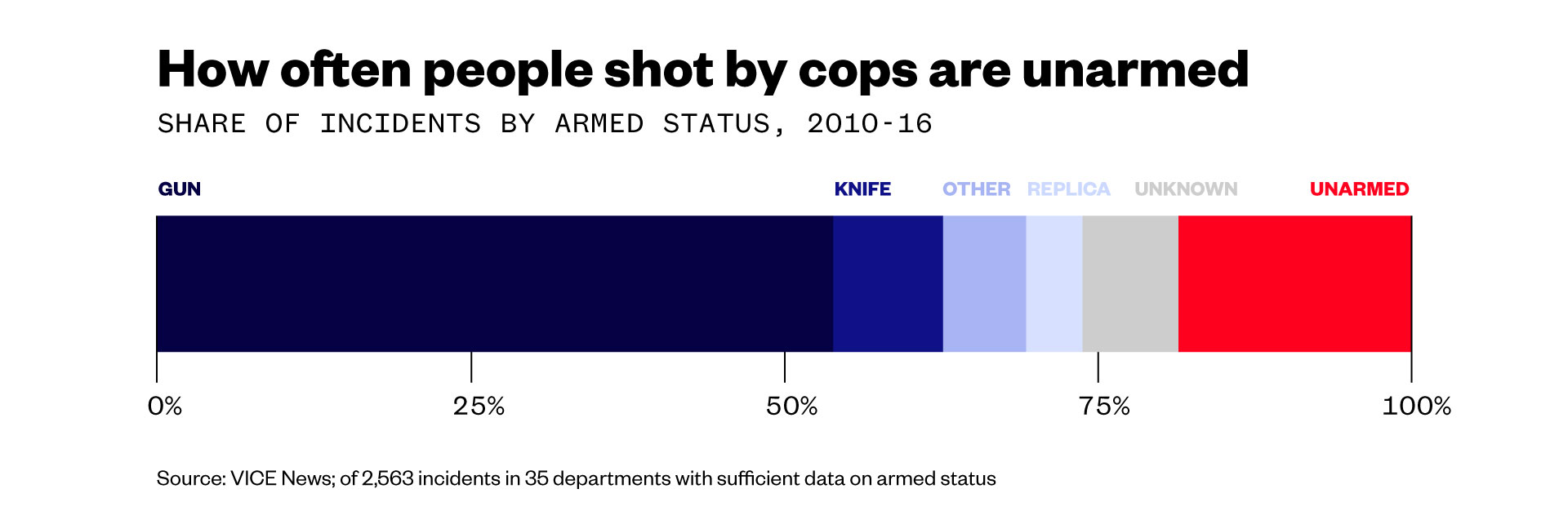

In roughly 8 percent of cases, departments didn’t say whether the subject was armed. About half of shootings occurred when officers encountered a subject with a gun. Another 20 percent of subjects were armed with a knife or something else.

Black subjects shot by police were more likely to be shot during incidents that began with routine traffic or pedestrian stops. They were more likely than whites to be armed with a gun but less likely to be armed with a weapon overall.

Download the data behind this reporting and learn more about the analysis

Beyond the numbers, interviews with dozens of current and former police officers, shooting survivors, activists, and independent experts described the devastating impact of police shootings on families and communities — even when the incidents don’t end in death.

“They often have the same impact on that community as a fatal shooting,” said Christy Lopez, who served in the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division under President Obama. “They will see that, they will be talking about that, hear the stories for years about what happened. The person will be the living testament to that shooting.”

Officers are hardly ever charged with a crime or even found liable in these incidents. Instead, many of the wounded end up facing charges — some even spend time in jail while still recovering from their injuries. In some rare cases, they’re able to sue and win settlements. A few become the focus of protests demanding reforms or turn to activism themselves. But most — hundreds of people nationwide each year — just go on living, carrying their trauma in obscurity.

DeAnthony Cunningham survived being shot in the back of the head by a Fulton County police officer thanks to at least a dozen surgeries, years of rigorous therapy, and the help of his mom, Felice Cunningham, who quit her job to care for him.

One of the most urgent questions about police shootings — and one of the hardest to answer — is what role racial bias plays when cops pull the trigger. Nonfatal shootings are key to answering that question.

More than a dozen departments did not release data on race or said they did not keep it. Race information was available for about 68 percent of incidents and 3,045 subjects.

This data shows a much graver impact on black people than previous efforts to track police shootings have shown. Police shot black people two and a half times more often than white people.

Police shot Hispanics slightly more often than whites, and Asians far less often than any other race. (Keep in mind that more people of color live in these communities than in the country as a whole, so rates are likely to be higher.)

Cases where cops shoot unarmed people often draw outrage, and looking only at fatal shootings excludes many of these. Nearly 400 unarmed people were shot by cops in this data.

In another 8 percent of cases there was no information about whether the subject was armed, but these people were probably unarmed, since police have good reason to record every armed subject. (Twelve departments, including Chicago and Los Angeles, didn’t reliably provide the armed status of the people police shot, so they weren’t included here.)

Nearly half of the unarmed people shot — 45 percent — were black.

Police officers and some academics say shootings reflect local crime rates or how often police come into contact with certain groups, not racial bias. In their view, it’s not fair to look at use of force by population alone.

Nick Selby, a Texas police detective and author of “In Context: Understanding Police Killings of Unarmed Civilians,” said it’s important to take into account the socioeconomic factors underlying crime and policing as well as the circumstances of each encounter.

“Deadly force has a disproportionate effect on nonwhite people, that’s true, but nonwhite people disproportionately engage in behavior that is criminal and dangerous,” Selby said. (Blacks and Hispanics are arrested at higher rates than whites for both violent and nonviolent crimes, but the research is unclear on whether they are more likely to commit them.)

Information about the circumstances of police shootings usually comes directly from departments, which have the opportunity to exaggerate or omit key details. “As we’ve seen, that account has many times been called into question,” said Samuel Sinyangwe, a cofounder of Campaign Zero, a group that advocates for police reform.

In one notorious case, the Chicago police officers involved in the shooting of Laquan McDonald in 2014 said the black teen assaulted them with a knife. That version of events was accepted until dashcam footage released the following year showed that McDonald was walking away when an officer shot him 16 times.

Not every department kept descriptions or full narratives of officer-involved shootings, but information was available on more than 1,800 incidents. One-fifth of the shootings of black people began as relatively innocuous pedestrian or traffic stops, compared to 16 percent for white people. On the other hand, blacks shot by police were more likely to be committing a robbery or involved in a shooting. Whites were more often involved in suicide attempts or domestic violence incidents and other serious crimes.

Black subjects also tended to be younger, and 10 percent were under 18, compared with less than 2 percent of whites.

“It is a complex picture, but what’s clear is that black people are more likely to be unarmed, and that more of these sort of low-level incidents escalate to shootings,” Sinyangwe said.

Ron Davis, who until earlier this year headed the Justice Department’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS), which works with departments to review their policies, said activists, cops, and experts can argue all they want over the best way to prove or disprove bias. It doesn’t matter much to the people who get shot.

“From the community that’s receiving it,” he said, “it doesn’t feel like disparity. It feels like bias — it feels like racism.”

Andre Thompson is still waiting for his younger brother Bryson Chaplin to come home from jail after both brothers were shot — Chaplin several times, leaving him paralyzed — by an Olympia police officer who responded to a shoplifting call. The officer said the pair attacked him and both brothers were convicted on assault charges related to the shooting.

When deciding whether a police shooting was justified, prosecutors weigh whether the cop felt a threat — not necessarily whether the threat was real. Laws dictating how and when a cop can shoot vary from state to state, but under a 1989 Supreme Court ruling, police force should be “judged from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene, rather than with the 20/20 vision of hindsight,” with an “allowance for the fact that police officers are often forced to make split-second judgments.”

In theory, most officer-involved shootings should be fatal. Cops aren’t supposed to fire their weapons unless they feel they’re facing a serious threat, and they’re trained to stop that threat. There’s a common misconception that police will try to disable a suspect by aiming for the legs or arms, but they’re typically taught to shoot at the center of the target, which often means they aim for the torso.

Cops and criminal justice experts emphasized that policing is an extremely dangerous profession and said it’s important to note that police shootings of any kind are rare.

“The average number of OIS [officer-involved shootings] for an officer over the course of an entire career is literally close to zero,” said Mark Iris, a lecturer at Northwestern University and a former head of Chicago’s police review board.

In our data, big departments with the most shootings had on average 32 per year, and smaller departments had as few as three. For cops and some analysts, that’s strong evidence that police use deadly force with caution.

Selby said the overwhelming majority of police shootings are justified. “Some officers are dicks, and if they hassle people, intentionally put the cuffs on too tight, or throw an extra punch or body slam, it’s really hard to prove, but every shooting is investigated,” he said. “We know cops shoot and kill around 1,000 people per year. I’d say 950 of those are justified, 50 are questionable, and 20 are really bad.”

Yet activists and some experts point out that it’s largely the police who decide which shootings are bad or questionable. The problem with the “reasonable officer” standard is the numerous cases that fall into a gray area. In these instances, a subject may be holding some type of weapon, but there’s no imminent threat to the officer’s safety. In others, cops may think someone is armed, only to discover he’s not.

Bruce Franks Jr., a protester in Ferguson who now serves as a St. Louis representative in the Missouri legislature, said cops in his city shoot first and come up with reasons later. St. Louis had the highest per capita rate of police shootings among the 50 departments we analyzed but provided scant details for shootings that happened after 2014. (A spokeswoman for the department said all shootings were investigated fairly.)

“There doesn’t have to be a gun involved. We see these cases where somebody has a cell phone or somebody makes the wrong move,” Franks said. “There’s a million reasons they give so it ends up being justified.”

A Pittsburgh police officer shot Leon Ford five times during a traffic stop when Ford’s car started to move, taking the officer with him. Ford later had to fight two charges of aggravated assault, but he was found not guilty. Since then, he has become an outspoken activist against police violence.

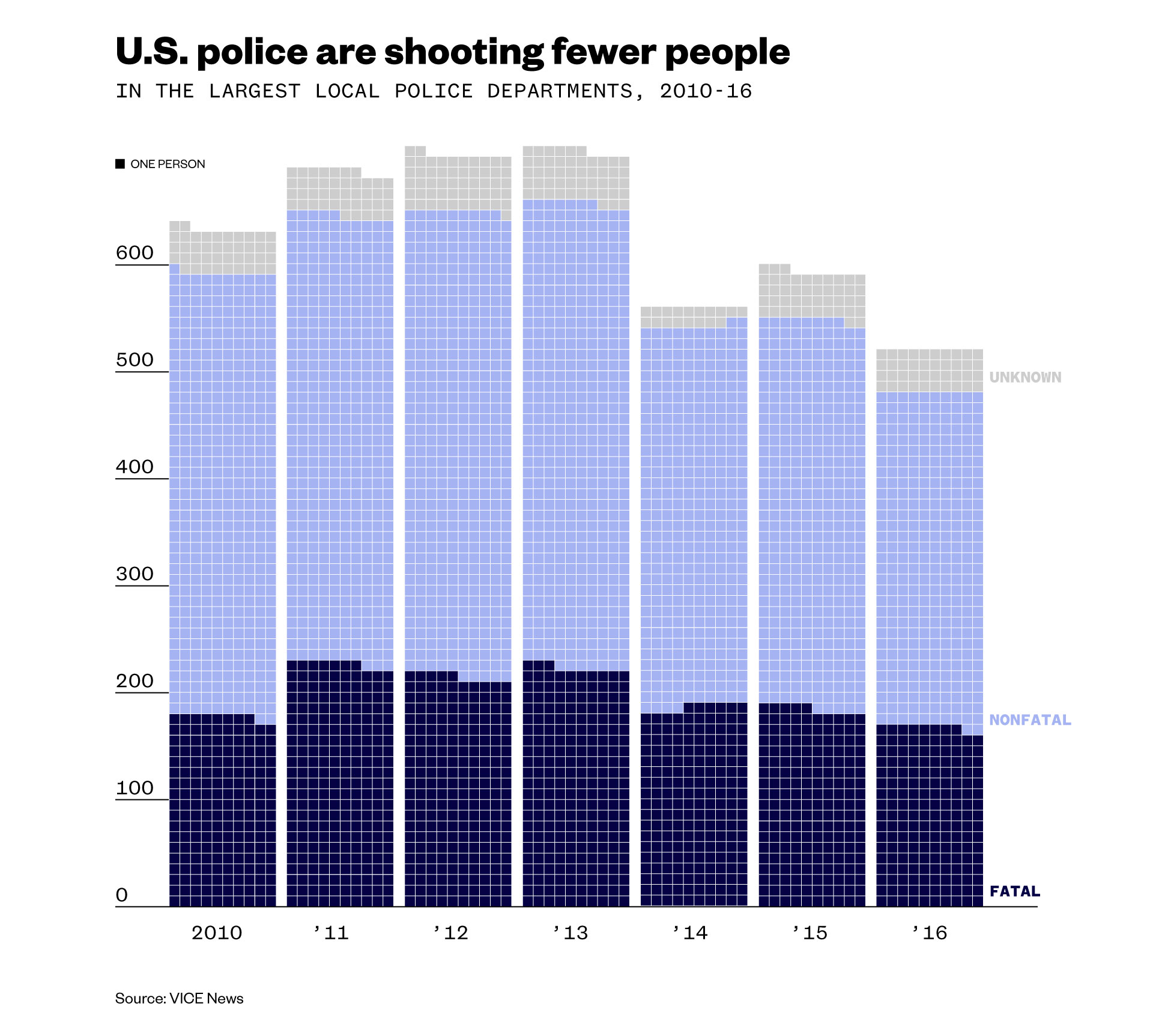

In the years since Ferguson, the total number of police shootings has fallen by about 20 percent.

That trend can be traced to a handful of large departments, including Philadelphia, Chicago, and Las Vegas, that enacted reforms. In fact, seven of the 10 cities with the largest reductions in police shootings had one thing in common: federal intervention.

Cities that voluntarily adopted DOJ-recommended reforms saw a 32 percent decline in officer-involved shootings in the first year. The police departments that were forced to take on reforms through binding agreements with the DOJ saw a 25 percent decline that year, including Baltimore, whose agreement began this year. In Chicago, shootings by cops dropped by more than 50 percent after McDonald’s death, an incident that prompted a DOJ investigation and a package of recommended reforms.

While the remedies varied from city to city, many were the same: Create a civilian review board to provide independent oversight, improve officer training, update use-of-force policies to stress the importance of de-escalation and the sanctity of life.

Despite these remarkable successes, Attorney General Sessions has announced his intention to “pull back” from federal interventions and effectively gutted the COPS office Davis used to run. Sessions has said that the feds shouldn’t meddle with local police affairs, but Davis said that approach is tantamount to “incompetence” and “malpractice.”

“I think it’s dangerous,” he said. “Not only is that an ideological response; it’s one that’s absent of science and one that ignores evidence.”

A Justice Department spokesman declined to comment on the record or to make any officials available for an interview.

For survivors of police shootings, reform — no matter how it is accomplished — can’t come soon enough. While academics, police officials, and politicians debate the merits of federal intervention or improved training, they live every day with the knowledge that what happened to them could happen to somebody else. Some live in fear of being shot again.

Ishmael Gough, a 27-year-old black man from Louisville, Kentucky, was shot in 2012 by a cop who was drunk and off duty. Gough was unarmed. The bullet passed straight through his leg, leaving him with a wound that still hurts when it’s cold. He lost his job as a security guard and his medical bills piled up. He used to have what he called “a basic, normal life.” Like many of the survivors who spoke with VICE News, he said when he goes out now, he’s “stressing, watching behind me, thinking something is going to happen.”

“I want to put it behind me, but I can’t stop fighting,” Gough said. “I was shot for no reason. It’s wrong that this could happen to anybody. Something needs to be done so it can’t keep happening.”

CORRECTION (Dec. 14): Due to a production error, an earlier version of the chart showing the effects of federal oversight over-counted the annual shooting rates for the Milwaukee, Albuquerque, New Orleans, Columbus, and Dallas police departments by about 1 shooting per 100,000 people per year.

CORRECTION (Dec. 19): The original analysis erroneously omitted 17 police shooting incidents in the Tampa Police Department and one incident in the Atlanta Police Department. It also misclassified 35 Hispanic police officers in Albuquerque as white. Numbers and charts have been updated throughout to reflect these changes.

Life after deadly force

Get the data on all police shootings

Rob Arthur,Taylor Dolven,Keegan Hamilton,Allison McCann,

andCarter Sherman reported and wrote this story.

Kathleen Caulderwood produced the videos.

Morgan Conley,Josh Marcus, andDiamond Naga Siu contributed research and reporting. Adam Arthur and Dylan Sandifer contributed research.

Illustrations by Xia Gordon. Design byLeslie Xia. Graphics byAllison McCann.

Read more about how we collected and analyzed the data.

More

From VICE

-

Members of the Raid, the special unit of the French police. Photo: Denis CHARLET / AFP -

(Photo via 11Alive News) -

A sniffer dog checks bags in England, UK. Photo by Maureen McLean/Shutterstock -

Photo by Gorodenkoff