This article originally appeared on VICE Arabia.

The story of Lebanon in the 2020s is a story of multiple crises occurring at once. Decades of corrupt rule by the Lebanese economic elites bankrupted the country, tanking its GDP and leaving 74 percent of the population in poverty, prompting Lebanese people to take to the streets in late 2019 demanding a revolution. But their efforts, culminating in the resignation of former Prime Minister Saad Hariri, were stifled by the ongoing pandemic, which caused major disruption to daily life and the economy as multiple lockdowns were implemented over the past 18 months.

Videos by VICE

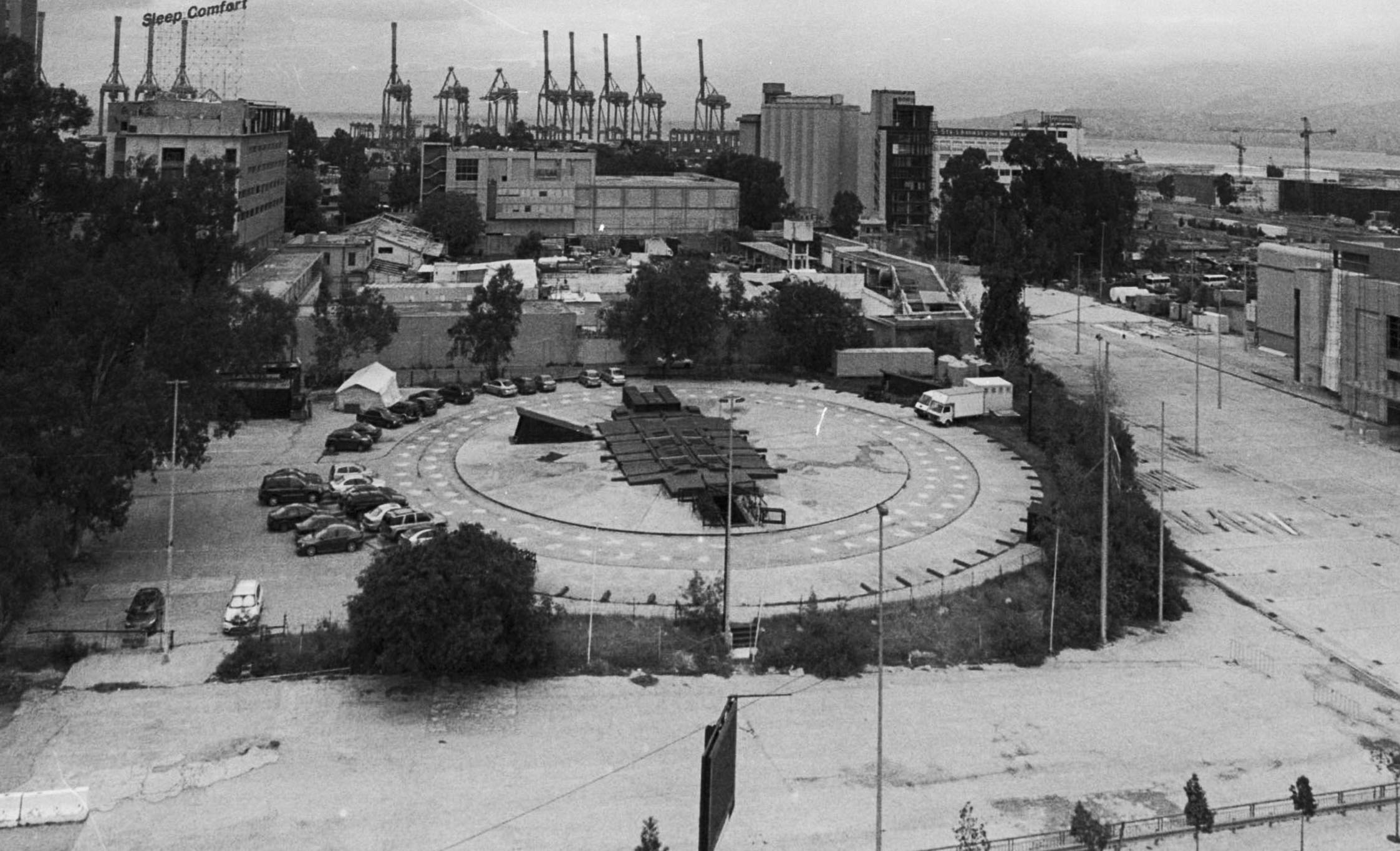

To top it all off, on the 4th of August 2020, a huge explosion at the Port of Beirut killed 218 people, left around 300,000 people homeless, and caused an estimated €3.5 billion of material damage, according to the World Bank. The explosion also exacerbated the country’s political crisis, as subsequent investigations revealed it was precisely institutional neglect that set the stage for the blast.

Among the buildings damaged in the blast were some of Beirut’s most highly-regarded nightclubs. For the global clubbing cognoscenti, Beirut’s reputation as a nightlife destination was up there with Berlin, London and New York. Over the years, clubs like AHM and The Gärten played host to house and techno luminaries including Sven Väth, Gerd Janson and Henrik Schwarz, earning Beirut the reputation of a city that never slept.

But even for the clubs that weren’t damaged by the blast, the party has come to a temporary end. In a country battling daily shortages of fuel, water, electricity and medicine, clubbing has obviously taken a back seat. In fact, most people without a generator have to make do with one or two hours of electricity a day.

As the situation in Lebanon deteriorates, it might seem like a luxury to think about the future of the capital’s music scene. But clubs like B018 and the Ballroom Blitz provided the city and its inhabitants with a source of happiness, experimentation and freedom of expression. They functioned for Beirutis like they do for clubbers the world over; being there was about more than just listening to music in a dark room late at night.

This past March, I visited the sites of the clubs that had one meant so much to me. I took these photos on film with an analogue camera, using whatever I could get my hands on. Since Lebanese money is worth next to nothing, importing goods is basically impossible, making camera equipment extremely difficult to find. Some of the films I had access to were black and white, others were expired.

I felt the need to give back to those places, even if they’re currently deserted. The lights may be off and the music is silent, but one day I hope that life will return to them, and to Beirut.