Scientists are currently searching for the submerged remains of an interstellar object that crashed into the skies near Papua New Guinea in January 2014 and probably sprinkled material from another star system into the Pacific Ocean, according to an onboard diary by Avi Loeb, the Harvard astronomer who is leading the expedition.

The effort, which kicked off on June 14, aims to recover what is left of the otherworldly fireball using a deep-sea magnetic sled. The team has already turned up “anomalous” magnetic spherules, steel shards, curious wires, and heaps of volcanic ash, but has not identified anything that is unambiguously extraterrestrial—or interstellar—at this point.

Videos by VICE

However, Loeb is optimistic that the crew will identify pieces of Interstellar Meteor 1 (IM1), the mysterious half-ton object that struck Earth nearly a decade ago, which he thinks could be an artifact, or “technosignature,” from an alien civilization.

“This has been the most thrilling experience in my scientific career,” Loeb told Motherboard in an email from the expedition vessel, called the Silver Star. “It reflects a unique opportunity to learn about other technological civilizations in the cosmos by studying the Pacific Ocean.”

“There is a periodic humming noise from the ship Silver Star when we retrieve the sled,” he added. “Standing in front of the ocean and waiting for technosignatures from the sled, make this sound like a dramatic drum roll.”

Loeb and his crewmates on this voyage, which is known as the Galileo Project Expedition, cast off on Silver Star from the island town of Lorengau last week and plan to continue scouring the seabed for signs of IM1 until June 29. Though the Silver Star is equipped with instruments for preliminary sample analysis, the team intends to study their ocean haul with far more precise and sophisticated laboratory equipment over the coming months.

The fireball that sparked the hunt smashed into the atmosphere on January 8, 2014, and was detected by NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS), which keeps track of extraterrestrial impacts using a network of sensors around the world.

Years later, Loeb and his student, Amir Siraj, concluded that the meteor’s high velocity at impact suggested that it was interstellar in origin, a hypothesis that was ultimately supported by the United States Space Command (USSC) using classified sensor data. Loeb and Siraj used the same method to subsequently identify what was likely a much larger interstellar meteor (IM2) that struck hundreds of miles off the coast of Portugal on March 9, 2017.

Both meteors were traveling at extreme speeds of more than 110,000 miles per hour when they slammed into the atmosphere, which is much faster than typical entities that are bound to the Sun. In addition to the breakneck pace, these objects appear to have been more robust than other space rocks, according to measurements of the fireballs.

The discovery of an interstellar meteor falling to Earth in this manner would be stunning enough, but Loeb—the Frank B. Baird Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard and former chair of the university’s astronomy department—wanted to explore possible alien origins for the object.

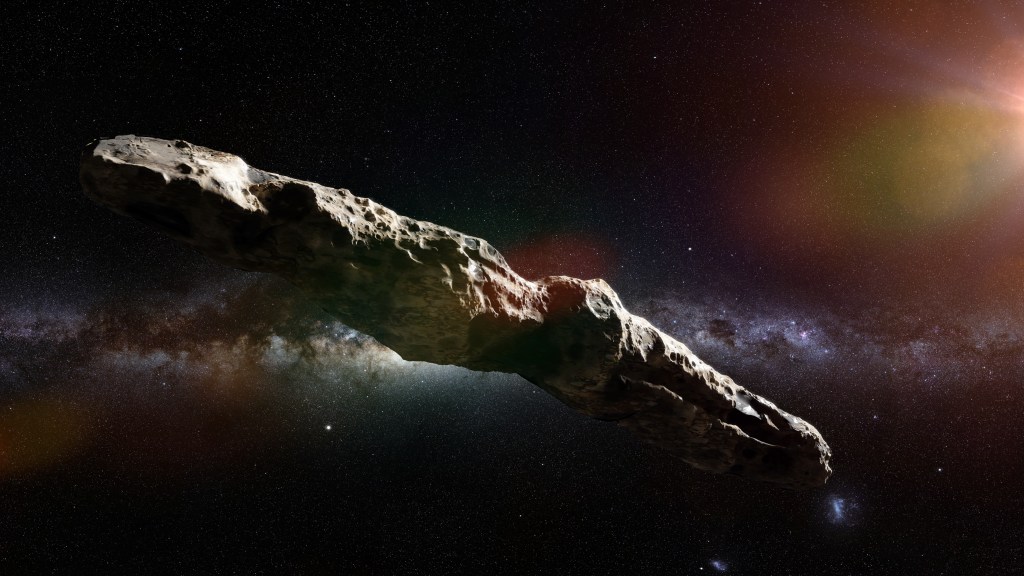

Loeb has sparked a good deal of controversy in his field in recent years due to his focus on finding evidence of alien life. He is perhaps most famous for his hypothesis that the strange properties of ‘Oumuamua, an interstellar object that zoomed through the solar system in 2017, are best explained by a technological origin, whereas most scientists maintain that ‘Oumuamua was a natural object.

It’s an unusually bold stance for a scientist of Loeb’s stature to publicly take, and one he’s committed to investigating. Now, his hunch that alien artifacts might be relatively common in the solar system has brought him to a remote stretch of the Pacific Ocean where the remains of IM1 likely splashed down, according to maps from the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD).

“We will criss-cross the entire error box provided by DoD for the location of the fireball of IM1,” Loeb told Motherboard. “We are planning on using a sluicing device in the coming days. If all goes well, this device will be able to separate high-density fragments from the background sand and volcanic ash, irrespective of the magnetic properties of these fragments.”

Specifically, Loeb thinks the material strength of IM1 and IM2 could be evidence that they are remnants of alien technology that traveled from distant star systems before exploding here on Earth, though he has also suggested natural explanations—including supernova “bullets”—that account for their toughness. He hopes that a clear detection of the meteoric fragments could not only provide an unprecedented glimpse of an interstellar object, it may even point scientists back to the meteor’s native star system.

“During the expedition, I had the insight that we can identify the star from where IM1 came by dating its materials using radioisotopes,” Loeb said. “We know IM1’s travel direction and speed when it entered the solar system. From its travel time, we can therefore infer the distance and direction of its point of origin.”

The object may have only left tiny splinters strewn across a huge area of seabed located at depths more than a mile under the waves, so the expedition certainly faces long odds of recovering this interstellar visitor. Undeterred, Loeb and his crewmates have spent the past week lowering a sled to scour the seafloor to search for magnetic particles that might belong to the meteor. The expedition is funded by donors including Charles Hoskinson, a crypto entrepreneur, who contributed $1.5 million to the project and is along for the ride on Silver Star.

On Wednesday, Loeb told Motherboard that the expedition had made its biggest “breakthrough” yet with the discovery of microscopic magnetic spherules hidden in volcanic ash from a recent seabed haul. Given that fireballs are known to rain down metallic spheres, the crew had hoped to find exactly this sort of material—Loeb had even written a blog post a day earlier entitled, “Where are the Spherules of IM1?”

The origin of the spherules is not known, but an initial analysis of the composition of one of these tiny objects revealed that it was made of mostly iron with traces of magnesium and titanium, and no nickel. Loeb called this combination “anomalous compared to human-made alloys, known asteroids and familiar astrophysical sources,” in a blog post about the discovery.

“We are now on our way back to IM1’s crash site in an attempt to retrieve as many spherules as possible,” he said in the post. “With a large enough sample, we can obtain a gamma-ray spectrum that will characterize its radioactive elements and potentially date the sample.”

The team has also recovered steel shards and a strange manganese-platinum wire wire, but it will take more time and research to determine the origin of all of these finds.

“Altogether, in our ten Runs of the magnetic sled, we have encountered steel shards only in Runs 6 and 7, delineating a fairly isolated geographic area not on a major shipping lane,” Loeb said. “These shards are not likely associated with a wreck because the spatial distribution is bigger than a wreck, and not trash or we would have seen it elsewhere.”

“It is also possible that dust particles from IM1 are hidden in the vast amount of black powder that we collected so far,” he added. To that end, the team is analyzing “a large quantity of the retrieved powder with our gamma-ray spectrometer to check whether there is any spectral anomaly relative to what is expected from volcanic ash.”

Regardless of its ultimate scientific results, the interstellar treasure hunt has attracted a lot of public attention. The Galileo Project, Loeb’s Harvard-based effort to find extraterrestrial artifacts, has run continual updates about the expedition on the Mega Screen in New York’s Times Square, and a film crew is also shooting footage onboard the Silver Star for a future documentary about the voyage.

“We just embarked on a terrestrial ship in search of the possible relics of an extraterrestrial ship,” Loeb wrote in a blog post on June 14. “For now, we will keep the champagne in the refrigerator until we find materials from IM1.”