A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium , a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Recently, the world (for a brief moment) lost its collective mind after learning that Microsoft was planning to retire its legendary Paint software, which has a lineage that dates all the way back to Windows 1.0 in 1985.

Videos by VICE

People calmed down some after learning that the company was creating an upgraded version of the app called Paint 3D, but make no mistake—the version of the barebones painting app that everyone grew up with is gone. It’s a great sign of the public seeing the historic value of something without any additional help.

But another creative platform’s widely reported death registered much more of a shoulder shrug in comparison.

Adobe’s Flash technology, which had gained a reputation of being more of an annoyance than a useful piece of technology, is starting up what is expected to be a three-and-a-half-year sunsetting period. And there are a lot of places where we no longer need it. But it’s worth remembering that when it first came to life, it was awesome—it created new ways for people to be interactive on the internet. And while it found its most common use as a way of junking up our pages, it also brought a whole lot of animation and interactivity to our web browsers—and all of those pages, of course, may not work in a few years.

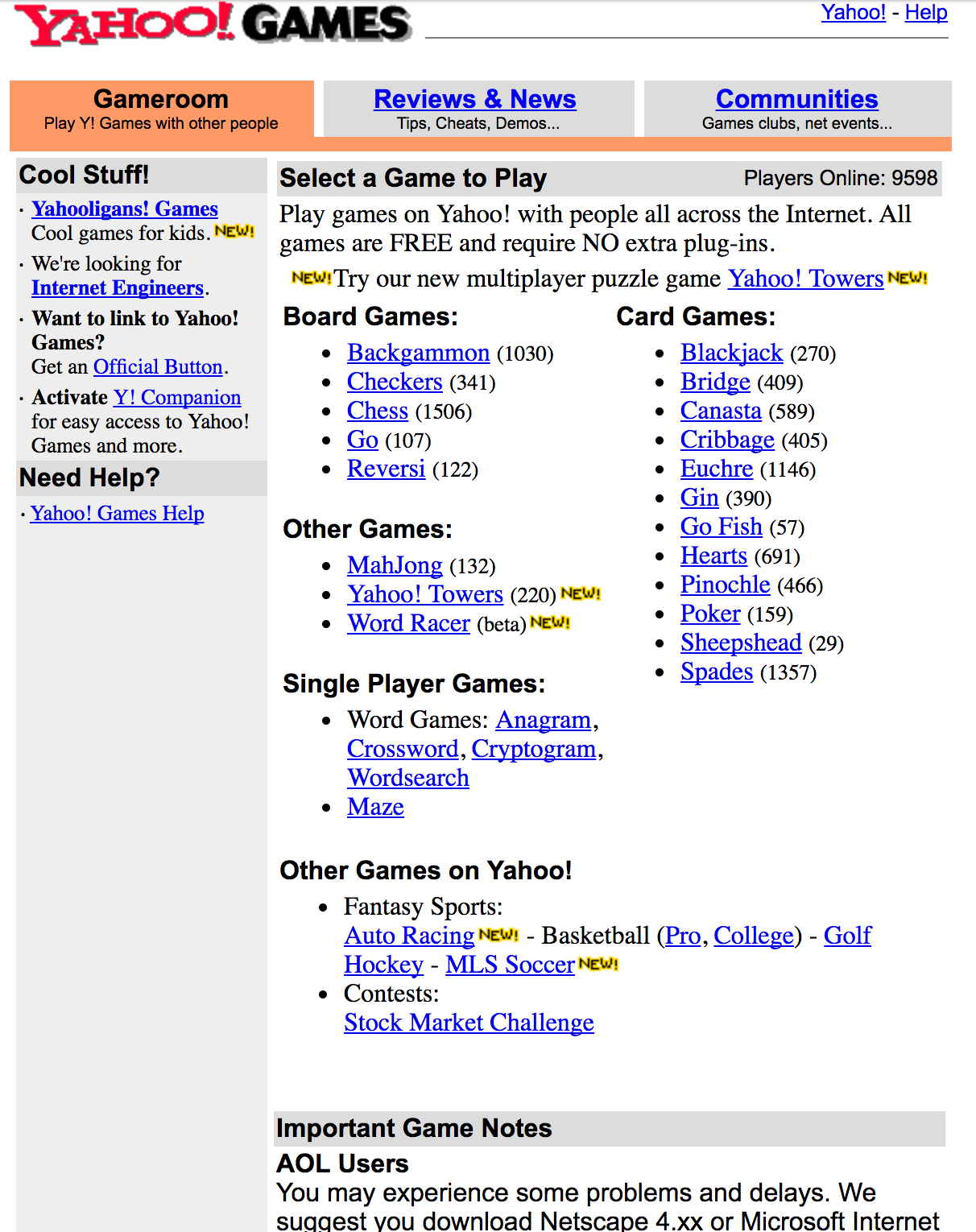

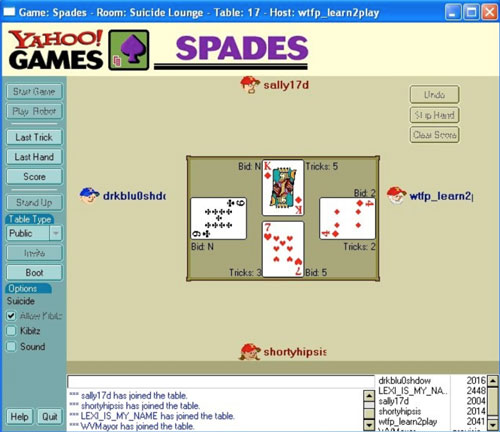

When all these Flash games stop working, what will that death look like? I assume it might be something like the demise of Yahoo! Games—specifically the original version of the Yahoo! Games platform, which didn’t rely on Flash, but a competing technology, the Java applet, that actually predated Flash by a few years. It was reliably square, but awesome.

And Yahoo!, of course, took it down all in the name of “streamlining.” As we ponder the next steps for Flash, a look at the destiny of Yahoo! Games might prove informative.

The pre-Flash technology that made it possible to build something like Yahoo! Games

In recent years, the word “Java” has become something of an annoyance for web users because of its constant security issues—and like Flash, it’s marked for sunsetting. But going back to around 1995 or so, it was genuinely exciting technology that blew a lot of minds.

Starting in 1991, Sun Microsystems began experimenting with a new kind of programming language designed specifically for interactive televisions, though when interactive TVs inevitably failed to generate heat, Sun and the language’s primary developer, James Gosling, moved the idea to the broader Web, which was just starting to grow.

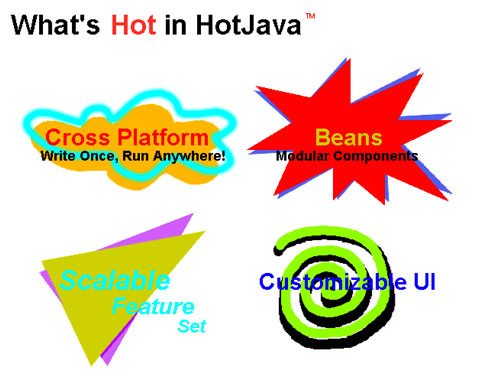

Sun’s goal with Java was to create a language that was able to run on a variety of platforms, not just Windows PCs, and in that spirit, Java’s developers experimented with putting Java code directly into the browser. The company created its own browser called HotJava, which was very limited except for the fact that it allowed for interactive “applets,” pieces of Java that could run in any web browser that supported them. It was a cross-platform compiler at a time when most stuff was siloed off. Java started a trend, one that other tools like Adobe’s Flash would soon follow.

One key element of that trend: Sun made it free, in hopes that it could change the dynamic of the internet and break apart Microsoft’s monopoly.

“Anything that contributes to the health of the Internet contributes to Sun’s health as well,” Gosling told The New York Times in 1995.

It was exciting technology, of course, but it was often confusing for users to keep up with it. As ComputerWorld‘s Frank Hayes noted in 1996, Sun Microsystems was trying to sell the web on Java applets at the same time it tried to sell a different form of software to businesses as a way to offer cross-platform applications. That meant it was a lot for non-technical people to wrap their heads around. It didn’t help, either, that other companies tried to borrow Sun’s nomenclature, most famously with Netscape’s creation of JavaScript six months after the initial release of Java applets, something Netscape also supported.

One information consultant, Eli Lily’s John Swartzendruber, noted this created confusing situations at the office.

“People say, ‘We’re going to do this in Java,’” Swartzendruber told Hayes. “But sometimes they mean JavaScript, sometimes Java, sometimes applets. Oftentimes I don’t think they know what they mean.”

Java applets were novel and interesting—at least until they inevitably became bogged down by security issues, which doomed applets as a viable web technology a few years ago. (Java, the programming language, lives on with Oracle, and is very much not going anywhere.) By that point, Flash, then JavaScript, had completely replaced it.

But back in the 90s it took a couple of years for a killer app to emerge. And that killer app was one that brought board games and card games back to life.

“Checkmate / Dennis Bell of Torquay / Too late / With your N at e3 / Good game sir / Do you want another bout? / Well Dennis ain’t replying / Cause he just signed out”

— A few lyrics from Half Man Half Biscuit’s “Bad Losers On Yahoo! Chess,” which is officially the best song written about Yahoo! Chess. It is one of the more popular songs drummed up by the satirical masterminds, who have written similar tunes for more than three decades. In a love letter of sorts to the song, Irish Times columnist Donald Clark had this to say: “What makes it so funny? I think, more than anything else, it’s the hint that the Great Nigel Blackwell is not entirely joking. He has certainly pushed the pieces about on Yahoo and I fear Dennis Bell might be a real opponent.”

How Yahoo! Games went from a small-time offering into a web conglomerate’s addiction play

Joel Comm is the kind of internet marketer that other internet marketers strive to be like.

His personal SEO is to die for. He writes books about internet marketing for a living. He’s been at this game longer than you’ve been using the internet, and it shows. (To give you an idea of how good he is at this: In 2008, his company built the most prominent fart app. Really.)

And perhaps, of the many big wins he’s had over the years, the biggest was what he did with a site called ClassicGames.com.

Around 1995, Comm ran a site called WorldVillage, an internet portal which attempted a “virtual city” kind of experience, along the lines of Apple’s eWorld. (It’s still online today.) Around this time, he caught wind of a University of Southern California student was building—an online platform for parlor games, like checkers, chess, and poker. Comm reached out, cut a deal, and helped to market the site.

Comm’s family-friendly WorldVillage was something of a mainstream play, and he thought was getting involved in something niche with ClassicGames, a site originally called Springer-Span. But it turns out that people love playing games online. In a passage from his book Click Here to Order: Stories of the World’s Most Successful Internet Marketing Entrepreneurs, he highlighted how he discovered this fact:

It was the Internet’s largest selection of Java-driven multiplayer games. In the beginning, given the total number of users online, I considered that a fairly narrow focus. But the Internet grew, and the site grew so fast we had to keep subdividing the users (three separate game areas became four, which became six) to keep from frying the servers—between November 17 and December 5 of 1997, the number of registered users jumped from 50,000 to 60,000. Finally it got so big that—oh, darn!—it caught the attention of a bigger company, who bought us out. The site is now Yahoo! Games.”

It helped that ClassicGames.com, beyond being fun, was a very effective model for interacting with other people online, with its chat-based interface and turn-based play. It asked less of its players, which meant it was perfect for casual gameplay.

“The funny thing is that these low-tech games work a lot better than the fast-trigger games when played on the Net,” writer Mark Glaser wrote of the multiplayer board game concept in the Los Angeles Times in 1997. “You don’t have to worry about your connection speed, buying an expensive CD-ROM game or being embarrassed by an overzealous competitor. Instead, you can play games often for free, sometimes without downloads, and you might meet someone interesting or win a prize to boot.”

(He did note that the Java applets were slow to load, however.)

The growth of ClassicGames.com, which only gained that name in July of 1997, was hard to ignore, even without a centralized portal to help it scale.

And there was an obvious portal on a purchasing tear at the time: Yahoo!, which bought the site in 1998.

Around the same time Yahoo! bought ClassicGames.com, it purchased a company called Four11, which made an email service called RocketMail. That became Yahoo! Mail. And not too long after that, Yahoo! bought Geocities and Broadcast.com, two major acquisitions that eventually died on the vine.

ClassicGames.com eventually would, too. But early on, it played an important role for Yahoo!, which was attempting to build, effectively, a web-native version of AOL—with content and activities so sticky that people would stay inside of its walled garden. Say what you will about checkers and chess, but they’re sticky games.

Unfortunately for Yahoo!, Facebook was simply better at building walled gardens.

How Yahoo! let a well-remembered platform die out in the face of corporate hubris

The concept that drove Yahoo! Games along with its predecessor—the idea that old-school parlor games are fun over the internet—was one that should have stood the test of time.

For one thing, it likely was a direct influence on the online poker boom of the early 2000s, as it was one of the first platforms to offer it. PlanetPoker, which claims to have been the first to offer real-money bids, did not start until 1998, while ClassicGames.com was active in 1997 with a poker server. (No betting, though.)

But Yahoo!, with its desire to be everything to everyone like an Everclear song, eventually diversified the site to an insane degree, moving far from the site’s roots as a simple arcade platform.

Here’s what it looked like in 2005, and here’s what it looked like in 2010.

To give you an idea of how far they moved away from the original idea: In 2010, the band REO Speedwagon launched a casual game on Yahoo! Games and other online portals, in an attempt to promote its music to the kind of music who play casual games.

“There is a need for us to explore all kinds of different avenues to get our music out there,” lead singer Kevin Cronin told The New York Times. “If you just think about how it used to be, you’ll be left in the dust.”

The problem with Yahoo! Games is the same problem REO Speedwagon had: All people really wanted were the hits, but they kept delivering more product anyway.

And when mobile hit, Yahoo! couldn’t keep up, so they took steps to dismantle what they had bought—much in the same way that they tore down Geocities a few years earlier.

The first thing to go was the ClassicGames.com domain, which was sold by Yahoo for $25,000 in 2010, according to Fusible, a domain holding firm and media company. The company retired the domain by 2006 and had been trying to sell it for a few years by that point. Currently, the domain is a placeholder spam site.

Next to go were the classic games, which Yahoo removed from the site at the end of 2014 after a failed attempt to refresh them. And with a acquisition by Verizon in the cards, Yahoo! shuttered the platform altogether last year.

Joel Comm, who made his name on that early bout of digital interactivity, was not happy about the loss, writing in a blog post:

I was saddened to discover that Yahoo! recently retired the entire ClassicGames library from their site, leaving fans of the games completely in the lurch. In fact, there are many who are very upset about this, not understanding why Yahoo! would just pull the games completely.

I can’t say I understand it either. But I know that the once mighty Yahoo! that had a chance to rule the web is alienating more of their user base with this move.

Was Yahoo! within their right? Sure. Was it fair to users? No.

Those servers weren’t hurting anyone.

From the perspective of someone interested in the internet history, the demise of Yahoo! Games—specifically, its earliest form, the reconstituted ClassicGames.com—is particularly depressing. See, unlike the websites or platforms I usually ponder, Yahoo! Games cannot be recreated. The Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine does not easily save experiences—no matter how important or fundamental those experiences are for internet culture.

Last month, as Flash’s forthcoming self-inflicted demise was being discussed, some were pushing for an open-source variant that could play all the files that were being pushed aside.

This was controversial for understandable reasons—why keep Flash alive when the goal is to take away a technology that holds a lot of downsides for the internet as a whole? I get that. But from a historic perspective, we’re playing a dangerous game right now, one that the saga of Yahoo! Games perfectly encapsulates. We’re locking the doors on a lot of the internet’s history in the process of washing away some fundamental ideas that just happened to be built with outdated technology.

It’s the kind of thing that leads enthusiasts to track down old screenshots from Prodigy data files, in a chance of recovering something, anything about a service that once meant a lot to them. Screenshots are easier to salvage in the modern internet era, but the interactivity of these creations, the sheer life and happiness that they brought so many people during a historically important time in the internet’s history? That’s the stuff that gets lost as corporate giants sunset these widely used technologies that have ultimately outlived their modern usefulness.

While the Java applet and Flash plug-in made the web more interactive, but it also made its legacy easier to kill. At some point, we’re going to have to demand some corporate responsibility on the part of our tech giants.

First off: It’d be great to get the old Yahoo! Games back.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.