…And then you had to ring a number and drive to a petrol station and wait there panic-buying Rizlas… and then you always had to drive round the entire M25 seventeen times… always exactly seventeen times…. and then you got there, right, and there were all these scallies, thousands of them, like buffalo, an army of shellsuits… well, shellsuits hadn’t been invented then, true, but… of course, back then pills all cost seventy five quid, which is about £8000 in today’s money, but they were all amazing, took you to literal outer space, I remember getting so buzzed I zoned out and just couldn’t stop orbiting the Crab Star Nebula… It was much more intimate too: actual Oakenfold spun Lil Louis for the first time with his fingernail in the groove rotating it round on my friend’s back…

1990 was one of those years when youth mythology was being cast forever. British ravers had never ‘ad it so good. All the cliches still seemed fresh. All the tomorrows began today. As the Berlin Wall came down and the dust began to settle on the new world order, optimism became the new watchword, happy drugs the new religion and for one brief fleeting moment, hippies stopped being pissed on by itinerant tramps and became the height of cool.

Videos by VICE

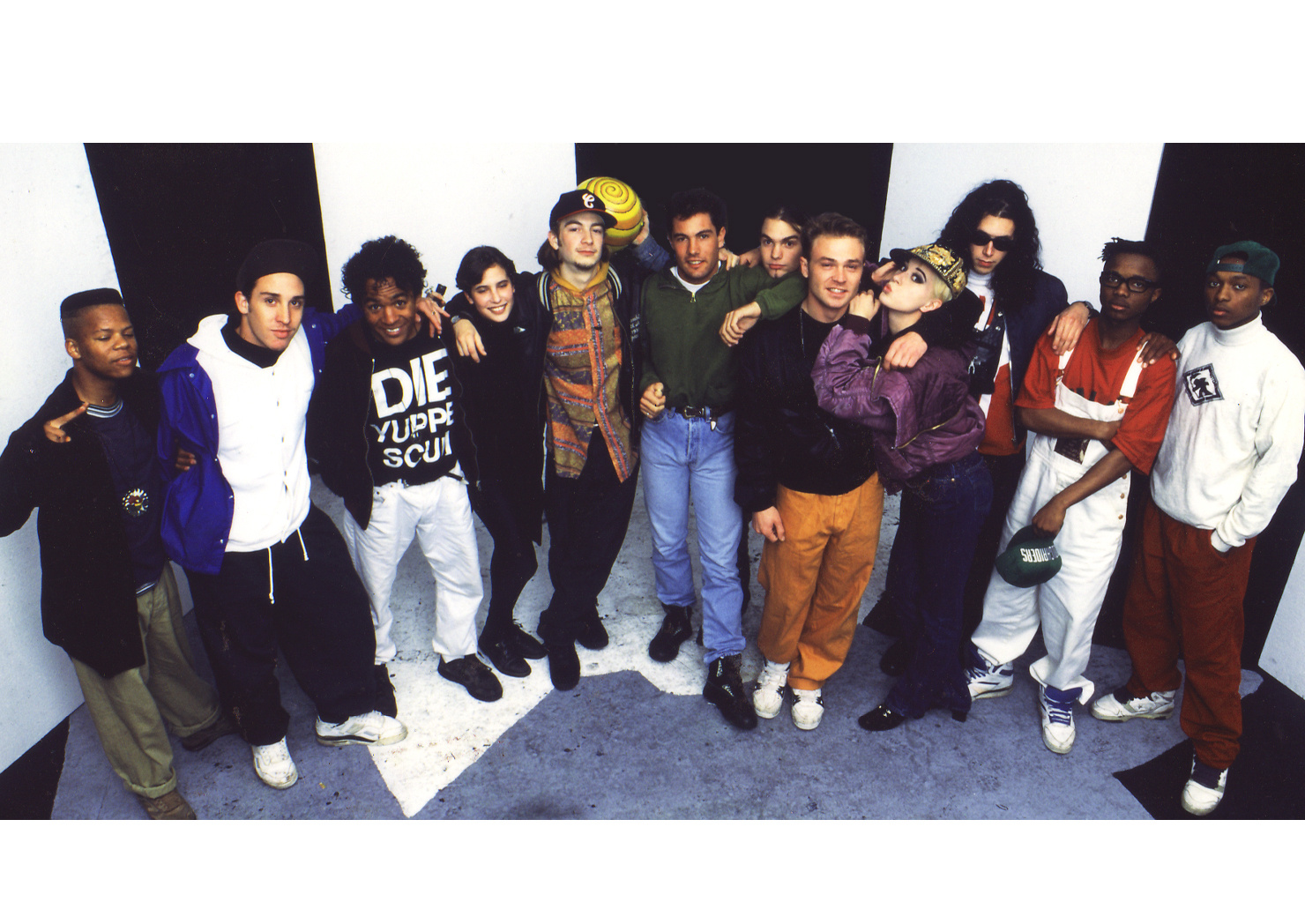

Britain was front and centre of all this. It defined the way the whole thing felt, what it meant. But at the same time, it wasn’t the only country painting it neon that year. Six thousand miles due south, a small clique of switched-on kids had, for one reason or another, washed-up in Cape Town, South Africa. Over the next few years, they would set about bringing the repetitive beats culture to The Dark Continent, and to a nation that was only just emerging from a cultural gloom far more profound and soupy than the usual trenchoats-n-cardies cliches of Thatcher’s 80s.

“South African nightlife at that time was shit,” laments Jesse Stagg, Eden co-owner number one, “It was a combination of awful eighties pop: Kylie, Jason, Boy George… and Goth stuff. Goths were really big here. But really, it was still stuck in the seventies. The Doors got played a lot.”

“It was all Armani suits and Saturday Night Fever. Very ‘cool’.” Carl Mason, partner number two, chimes in, “I was depressed. I had given up a massive party lifestyle in the UK to come there, and I remember standing round at times, thinking: ‘God, what’ve I done now?’”

The place was more than a little backwards. This, after all, was a nation that had only gotten television in 1978 because the Nationalist government thought it’d be a corrupting influence. In the South Africa of 1990, you still had to smuggle your Fawlty Towers episodes in on home-taped VCR cassettes because of the Equity boycott. When they weren’t listening to bootlegged Rodriguez records or being conscripted into the army to fight illegal wars in Angola, young white South Africans liked to unwind by being between two and five years behind the rest of the world.

But by February 1990, a newly-released Nelson Mandela had stood on a balcony at Cape Town’s Grand Parade, and told everyone they were soon going to be free to feel good. Change was in the air. Even if it hadn’t quite landed on the ground. Jesse and Carl had met in what was then the centre of Cape Town’s nightlife. Idols. What you might call a ‘discotheque’ just off Shortmarket Street that fulfilled the needs of its fauxsophisticated clientele with faux-sophisticated lampshades, gaudy dark wooden floors and plenty of mirrorballs.

Stagg’s dad was a screenwriter who’d hit it big. He’d grown up flitting between South Africa and LA. He remembers taping industrial quantities of hip-hop off of US radio and porting it back whenever he was sent home. Carl’s own father had remarried, and he’d come out to Cape Town for a week for the honeymoon. In a weedy haze, he had somehow forgotten to return to England and started working in a trendy clothes shop downtown instead.

By 1990, though, he was starting to have pangs of regret. He’d already been big into the UK scene and even claims to have hosted the ‘first-ever outdoor acid house party’, in his very big English garden outside Romford. Will Hutton, their third partner, takes up the story: “Carl phoned me up and asked if I wanted to play a few records. I knew he was at art college. I assumed it would be just a few mates. But he had two big marquees set up. Two thousand people inside, and another two thousand banging on the gates, waiting to get in. The riot police were all outside, and Boy George, Sade and Aswad had turned up. Paul Oakenfold and Danny Rampling were playing. I remember getting terribly excited and scoffing perhaps a bit too much E. I was introduced to Danny Rampling, went to shake his hand, missed, and collapsed at Boy George’s feet.”

As they bonded over Idols’ awfulness, Jesse mentioned he was looking for a housemate, and within a week, Carl had moved his only possessions: a bed, a TV and a surfboard, into Jesse’s place, and soon, the pair had begun promoting occasional warehouse parties together under the tag UFO, for Unlimited Freak Out, starting with a regular Saturday night mash called Front in a dingy room on Long Street, playing a mixture of acid house and hip-hop. “Which was much more common in those days,” Stagg says. “What people forget is that in those days there was a lot of overlap. Whether they knew it or not, most hip-hop artists of the time had at least one house record on their albums.”

Whereas previously you knew where you stood, ethnically-speaking, in the interzone between The Doors and Grandmaster Flash, acid house represented a fresh meeting point between the tribes. In the South African context, with the segregation laws now left dangling, on the books but unenforced, acid house marked the zone in which kids from different sides of the literal train tracks that ethnically cleaved the city could finally get fucked-up together.

So it was that, to find a DJ with a suitable supply of super-pricey entirely-imported vinyl, he went across the tracks, to the hip-hop side of town. DJ Rozzano, ‘one of the first people to play house in SA’, according to himself, who’d been in residence at what was then the only

mixed-race club in town: The Base. “The Base was an afternoon show,” Stagg explains. “Because of the way the city was designed, most of the non-whites lived on the edge, so the sheer distance and lack of transport meant it had to be in the afternoon so they could get home.”

“Us brown people had only really started to come into the city about then.” Rozanno recalls. “Before it was illegal. Technically, it still was. I met Jesse there. He heard me DJ, then he asked me to play at some of his warehouse parties. Racially, I’d say it wasprobably about 60-40 in there. 60% white. 40% black and brown. Mainly brown. It was fresh. It was exotic. It was 1990. Mandela just came out. It was in that first wave of mixed clubs. For us, we were used to dancing alongside black people, but it was still strange to dance alongside whites.”

A few months on, they hit their watershed with their World Peace Party. “The flyer was the hippy ‘peace’ logo,” Stagg explains, “But some local Christian organisation had starteddefacing the posters we were putting up around town. They claimed it was Satanic. Very Cape Town reaction. So we got onto the radio stations, and ran with that one. We put out a statement saying these people were anti-peace activists. It ended up on as an item on the news. Got a whole load of free publicity out of it…”

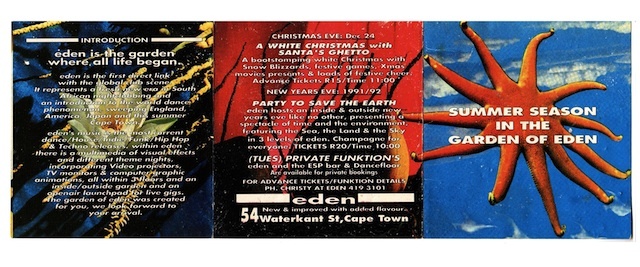

From across the racial track-lines that cleaved the city, four thousand people turned up to a warehous in Paarden Eiland industria, a mini-Woodstock by the standards of the time. By 10AM the next morning, as they sucked in lungfuls of poppers and stale sweat (and came to the unnerving conclusion that their silent business partner had run off with their entire cash-pile), the duo became convinced that the scene had reached a critical mass. They enlisted a handful of friends as partners, Stagg resigned from his job in adland, and within 48 hours they had raised R100,000 (about £60,000 in today’s terms), to open Eden, a thousand-capacity, purpose-built venue on the edge of downtown, in the shell of what had been an ice cream factory.

“We really were – and I’d just like to push this out into the ether to see if anyone agrees – one of the first ever superclubs,” says Stagg, “This is three years before Cream and all that. Everyone was still just putting on one-off parties in unimaginative environments. But

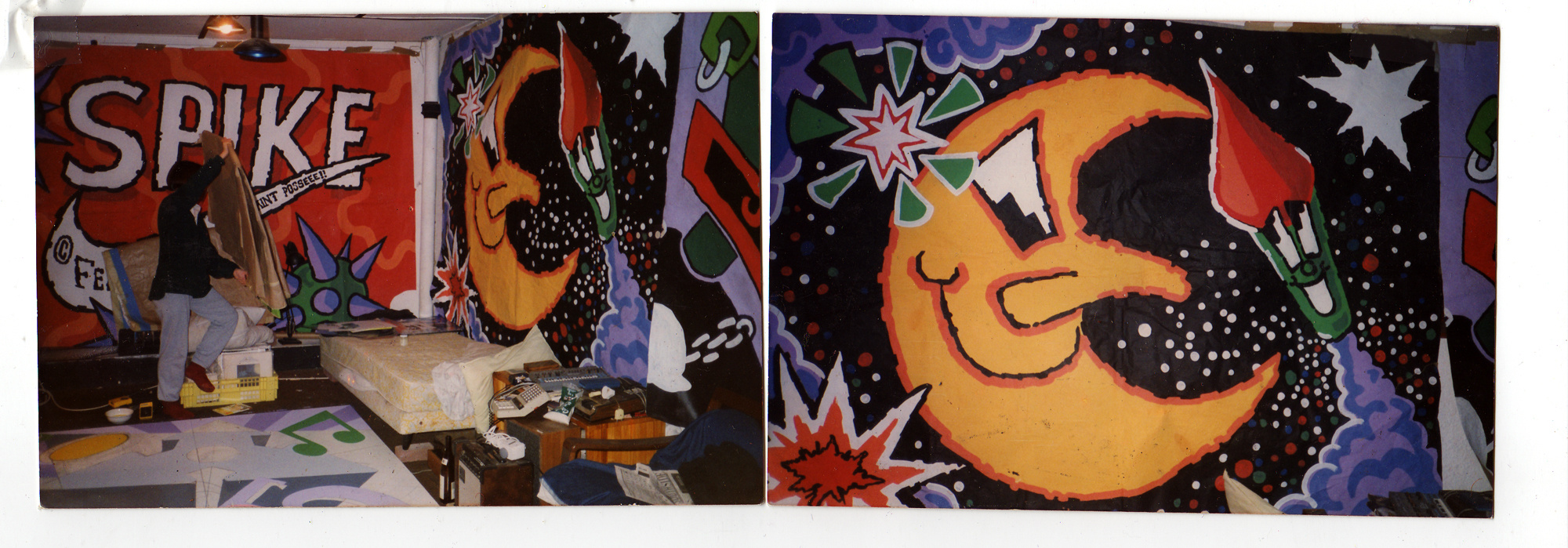

Eden had a brand, a very defined logo, and a set of values that went beyond a simple space for people to dance in.” They traded on that idea of being a freeform art party. They put put a giant blow-up whale in a net above the dancefloor. Their bouncers wore purple, actively acted nice, and were known as the ‘Guardians of Eden’. They painted trompe l’oeil decals of babies on the walls and looped video art on massive screens, including Kenneth Anger’s Feminazi flick ‘It’: an hour’s worth of interviews with women talking about their husbands penises. The only visual was the sequence of these various, varied penises, projected nine foot tall against the club walls.

“We’d used to sit around opposite it, just watching people’s reactions,” Stagg recalls. “The decor homaged the Hacienda. It was fruity-industrial. The walls were all painted different colours. We had big columns, painted silver. Big cross-girders at the top. We got these big half polystyrene balls, painted them silver and stuck them to the walls, so it looked like the whole place was riveted together. There were yellow chevrons around the dancefloor. But the entrance to it was on the upper level, so to get to the dancefloor, you’d have to come down a long ramp. It creates a certain effect, walking down to get there. There’s anticipation, and you can see the lights, and smell the smoke, and start to feel the energy that’s coming off there. Once you’re there, you feel ensconced. You feel like you’re in the belly of the beast.”

“It was very experimental,” recalls regular Matthew Quinton. “I remember, in the middle of a playing ‘Little Fluffy Clouds’ by The Orb, the music stopped and all the lights went out, and they turned on a single, low rotating blue light – like a police light, and brought in dolphin’s cries, whale music. And everyone was silent. They all came out of their internal trips, and looked around at the people next to them. Then, gradually, one-by-one, they began experimenting with dancing to this new sound, and moving with each other, until you had this writhing wave of gently swaying bodies. It was, clichés aside, a place of internal discovery. It was both a womb and a rave-floor. It mixed feelings of danger and safety in equal measure.”

In the womb, tomorrow’s taste-makers were being gestated. Just sixteen years old at the time, future top South African house DJ and Mutha FM founder Nick E Louder remembers Eden as “Quite weird. It closed and re-opened, and then got even weirder… People were

trying to express themselves – it was all bright colours, day-glo oranges – people copying what they’d seen in magazines, I suppose. Girls used to body-paint themselves, and be naked but for the paint. You’d sit there, just checking them out…”

The man who helped set up the next wave of South African raves, Synergy co-founder Chavda was eighteen when he first stumbled into their orange taste-uterus. “It was, truly, the greatest club there has ever been in Cape Town. They used to play everything at 124bpm, because that was the speed of a baby’s heart inside its mother’s womb. And their flyers were from the future. They used to make ‘em out of anything – perspex, knickers, they could afford to spend because they were guaranteed about a 50% response.”

Of course, given what a small and isolated scene they were enjoying, Eden lacked a lot of the supporting paraphernalia. Clothes, for instance. “Nothing that seemed appropriate was actually available at the time,” says Quinton. “So people used to make their own clothes. You would go round to someone’s house on a Saturday night, and spend three or four hours tailoring your outfit. I used to have a woman in Greenmarket Square who made all of mine. Every three months or so it’d be: ‘Right, time for a new outfit…’ There was no uniform, not like what house club dress codes became. I remember walking into the bathroom, only to see someone dressed as a giant frog walking out. People who didn’t even like dance music used to go there just to get to wear their S&M outfits. I often used to come in off the beach, just in a tatty t-shirt and shorts.”

And for a while at least, something else was still missing. Will Hutton: “I had come out of the huge acid house scene in London. But when I arrived, ecstasy hadn’t hit Cape Town, and it didn’t until the late part of the first season. But there was the same E euphoria as in London. People were still giving it rock-all without the chemical power behind them. That quite shocked me. I was always like ‘Well, where is it?’ and people were like: ‘Well, we haven’t got any…’ And I was like, ‘Well, what are you doing, then?’”

Stagg: “They were very tricky to get hold of at first. You often had to make other plans. Acid was big. And then there was something called ‘Dr Baxter’s Slimming Tonic’, which you could only get from one pharmacy, down in Sea Point. It had big letters on the side: ‘WARNING: NOT TO BE TAKEN AFTER 4PM’. I remember going past there on afternoon and seeing this long queue of already very skinny ravers all lining up there to get their new supply of slimming tonic…”

“It wasn’t really an E thing in the first season,” Quinton explains, “Back then, you’d sometimes be lucky, and have a friend who had come back from London, and smuggled a bunch in their suitcase. But more often, you’d have to settle for acid. The drug-taking wasn’t so in-your-face. There was certainly very little coke. But the second season…”

“Why did we call it Eden?” Stagg grins, “Because we wanted it to be a massive E den…”

It soon became a massive E den. And as is their wont, soon enough things ended up going a bit Tony Wilson. By early ’93, the club was haemorrhaging cash. In their haste, the duo hadn’t bothered with the ordinary chain of legal papers. There were no proper contracts between the partners. Some were increasingly anxious about seeing a return. Some weren’t getting on with others. One had been replaced: unbeknownst to everyone else, he’d been backed by an Israeli businessman, who, fancying himself better-suited to club management, had actively taken over his passive share in the business. “We just rocked up one day, and we were told we had a new partner – Shirek, I think his name was,” Carl recalls, “It was about that time things started getting really weird, actually…” The brothel that had been on the top floor of their building had moved out, upset about the constant noise. So they’d inherited a new suite of offices: with four showers and twojacuzzis. The drugs were becoming ever-more freely available. The drugs were becoming a problem.

As the sad story told a thousand times goes, the idealism that had birthed it had given way to selfishness. In the end, the partners simply pulled the plug. They walked away without recouping a cent. “But it was never about the money, anyway,” Stagg considers, “It was about doing something original. Just last night, I showed the Eden logo to this girl, and she flipped out. She used to go there when she was a teenager. I meet people in LA, in London, all over, who used to go there. We turned-on thousands of people to what was happening. What’s the price of that?”

Follow Gavin on Twitter @hurtgavinhaynes

Like this? Read more World Unknown:

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Group4 Studio / Getty Images) -

Collage by VICE -

Photo by Hollandse Hoogte / Shutterstock -

Collage by VICE