While Spike Jonze’s recent film Her imagined many possibilities about the near-future, one of the subtler prophetic aspects of his love story hypothesized the next-frontier of video games, including interactive characters and controller-free consoles.

The movie’s protagonist, Theodore, could possibly even represent the gamer of tomorrow, and his video games of choice are equally futuristic, even if they are technically design fiction and only exist within the movie itself.

Videos by VICE

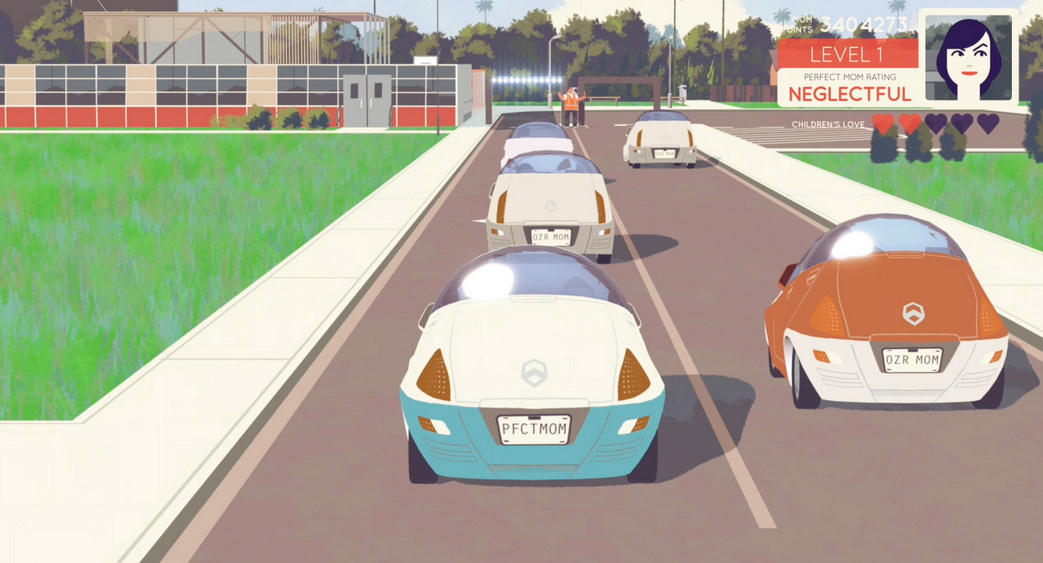

The first faux-game in the film was actually created by designer David OReilly. It features a foul-mouthed alien child that guides players through holographic tunnels while hilariously insulting the player. The other video game in Her, designed by Kevin Dart, challenges players to be ruthlessly perfect Moms.

OReilly’s game is physically immersive as well as seamlessly integrated with other tech, including the Samantha OS. As we watch Theodore play, the game feels like a natural extension into an imagined environment. “Perfect Mom” (made at the fake company “Be Perfect”), suggests the gamer profile has expanded to include a much wider and maybe unexpected demographic.

OReilly and Dart are both known to work as directors in the animation world, so it’s no surprise the games have a highly stylized point of view. More than anything, “Alien Child” and “Perfect Mom” together suggest that specialized video games will continue to play an integral role in the future of entertainment.

We emailed OReilly and Dart to find out what it was like to make the faux video games of the future.

David and Kevin, would you mind each giving me some background on your careers?

OReilly: I started making short films in my bedroom and posting them online.

Dart: My background is actually in video games. I went to school for 3D animation with the goal of getting into the video game industry, and after school I worked as a character modeler at a local game company for about two years.

I wasn’t really working on the kinds of games I wanted to so I eventually left to pursue my design and animation interests. The first jobs I got were working freelance on some UK-based projects that eventually led me to work with director Pete Candeland and Passion Pictures. Through those early projects I also met my good friend and frequent collaborator Stephane Coedel (who also worked with me on Her), who’s a brilliant compositor and animation director.

Since then Stephane and I have collaborated on several short films & commercials, and I’ve worked on lots of TV & film projects for the animation studios here in LA. Most recently I art directed the Cartoon Network series Steven Universe as well as the new 3D Powerpuff Girls Special.

How did the opportunity to work with Spike arise? And what exactly was the prompt?

OReilly: Spike had seen a short I did called Please Say Something a few years earlier and people close to him were kind enough to recommend me. They wanted to explore the idea of doing the animation outside of a giant studio, which is the more traditional route for a film of this scale.

What was it like to work with Spike?

OReilly: Spike is disarmingly friendly and terrifyingly convinctive. He’s a massively inspiring person to be around.

Dart: Spike was amazing! He was super generous with his time and really focused, but also playful and always kept the meetings fun and not too serious. I was really intimidated to work with him because I’m such a big fan of his work, but the first time I met him he was just the most normal guy and he offered me some “really good” chocolate. Sometimes he brought his guitar to our meetings and would just strum along while we talked through animation notes and stuff.

Can you walk me through the production of each of your games? How did you move from original concept to delivery?

OReilly: I worked conceptualizing the game in 2D & 3D for about 6 months before actual production. We went over every detail of the characters and environments, the Alien Child probably going through the most iterations. When animation began we were presenting versions every other week–many changes happened right up to the final deadline.

Dart: In our first meeting Spike walked me through the Perfect Mom sequence and described what he was hoping to see. They had a really early storyboard cut into the movie, but it still needed a lot of work and didn’t really describe what the visuals were going to be like. Spike gave me a ton of references, everything from David Hockney and Alex Katz to the graphics in Google Earth, and said “make something like that!”

So we began by focusing on finding a visual style and after a few passes I found a style that captured all of the stuff Spike wanted. The first things I tried to nail down were the design of the Mom and the kitchen. After that I moved on to designing the other environments like the neighborhood and the school… We also spent a while in this phase working on the design of the Mom’s car. The car was an interesting challenge because they had specifically avoided showing any cars in the movie, aside from one taxi, so there wasn’t a lot to work from. We really had to figure out what cars might look like in the future world of the movie…

Eventually we had a pretty solid look figured out for the whole game and I moved on to creating a more fleshed out storyboard to work with the new designs. We pretty much stuck to the script Spike had written, but also tried to work in some visual gags and stuff where it made sense. It was important to make sure everything matched the dialogue from Theo and Amy since the live-action scene had already been filmed. Even though there was just a blank screen in the footage, it was really clear that the actors could “see” what was happening in the game and were reacting to it and we had to try to match that…

At this time Passion was also getting started on modeling the mom and doing some animation and rendering tests. Spike was very specific that he wanted the final 3D animation to look as close to my paintings as possible, so Stephane (Coedel) did a lot of experiments to achieve the right sort of feeling with the textures. The characters and the environments all have some effects on them to make them look like animated paintings. They also built the 3D kitchen set with this really wonky perspective in order to match my wonky painting.

Once the storyboard was approved and timed out, Stephane and the guys in London moved ahead with animation and we would just do regular check ins with Spike. We would also record Spike sometimes in the meetings because he was super good at acting things out, and the animators used the video of him for reference of the Mom’s movements and expressions.

Who were your collaborators? Who wrote the video games’ scripts?

OReilly: I brought on my friends at Titmouse to help make the animation. They’re traditionally a 2D studio but we had talked before about wanting to do 3D together and this was the perfect opportunity. The actual production team was very small, most of the work being done by four people. Spike had written and recorded both scenes beforehand, there were just a few ideas that came up after. Spike also voiced the Alien Child.

Dart: Spike wrote all the Perfect Mom stuff, including the messages that pop up (“You’re Failing Your Children!”). He was really open to suggestions though, and we came up with some visual gags he liked, like the kid dumping the cereal on his head or the HUD in the corner of the screen that monitors the kids’ love for their mom.

The rest of the Perfect Mom team was in London, where Stephane was in charge of compositing and also directing a team of CG artists at Passion. The modeling was done by Matthias Bjurstrom and Ian Brown, rigging was done by Chris Dawson and Morgan Evans, lighting and rendering was done by Quentin Vien and Will Broadbent, and animation by Constantin Paeplow, Kyra Buschor, Conor Ryan, and Wes Coman. I also got some help in designing the jealous moms, the kids, and other incidentals from the amazing Emmanuelle Walker!

Though I imagine you only built the scenes we see in the movie–how was thinking about design, animation and story within the context of an interactive video game different than what you usually do?

OReilly: Because this was set in the future and game technology evolves so rapidly, we didn’t want to reference any typical or contemporary game motifs. The goal was to make it visually elegant and mechanically complex. So for example, in one scene we see the avatar character running for 30 seconds. The movement needed to be organic and varied rather than a looped cycle, the character had to feel aware of his environment. There was also enormous focus put on the subtlety the Alien Child’s acting, more than I had employed in any previous project.

Dart: This was indeed my first fake video game, but I think my experience in actual games made it a pretty natural fit, and it was super fun to mimic a lot of gaming conventions like the HUD or the GTA-style camera during the driving sequence. Stephane is a big gamer too so he knew exactly how to direct the animation and everything to feel like this could be a real video game.

Each of your video games serve as comic relief, but also drives home how radically social and seamlessly integrated technology is in Theodore’s world. I’m curious how you considered your small piece within the larger story?

OReilly: Well it’s a magic trick. It looks like a comic aside, but the idea is that games have more of a presence in the future than movies. They also represent another aspect to the ubiquitous presence of AI in Theo’s world. His only friend in the movie (Amy Adams) is also a game designer.

Dart: To be honest, the first time I saw the movie I felt like our contribution was really insignificant because the film is so overwhelmingly beautiful and touching and filled with all these other amazing things. But since it’s come out I’ve been really amazed by the reaction it’s received and especially how many people remember and enjoyed the video game sequences. I just feel super proud to have been a part of this movie and if people enjoy our one minute of video game silliness that just makes me super super happy.

David — did you weigh in on the way your game is projected or the gestural navigation?

OReilly: The scenes were shot with 6 small projectors dotted around the room; the room was then tracked and rebuilt in 3D. I spent about two months creating the technique for doing the hologram’s “nested perspective”, where the game has it’s own perspective inside the perspective of the room. At times the setup was maddeningly complex, your brain kind of melts into the software to the point where you’re not consciously aware of how it’s working. The gestural navigation was designed to make the game as immersive as possible. It controlled the motion of the characters hands and feet as well as game-camera and photo switching. Since holograms of this kind don’t exist yet, we worked hard to make the technical nature of them didn’t stand out too much.

Explosively popular indie games like Kentucky Route Zero and Broken Age are pushing video game aesthetics to new places. A game like Night in the Woods is a good example of a more traditional animator diving into creating a game. Curious if either of you have a desire to make an actual game?

OReilly: Absolutely. I got into animation from a love of cinema but if I was starting now I’d surely be making games. I get more e-mails from game designers inspired by my stuff than anyone else and it makes me feel like an old man. I’ve been saying it for years; the indie game scene is way more active and exciting than the indie 3D scene.

Dart: Yes. I’ve been outside of the gaming world for quite a while now but it’s still my first love and I’ve been dreaming of making my own game since I was a kid. Seeing the things being made now (like all the games you mentioned above) is pretty intimidating for me because I don’t think my ideas are super innovative and I would probably rely on more classic game mechanics from the sorts of games I grew up with on the NES and SNES. So sometimes I worry I’m too old school to keep up with all of these amazing projects people are creating, but I’d still love to give it a shot!

How did working on these pieces make you think about the future of video games? How might future games help us cope with or escape I the world around us?

OReilly: Games (like all art forms) help us understand the world around us, and they’re moving into brilliant new territory. I don’t think there’s an ‘average game player’ anymore, so I’ve no doubt the conceptual scope of games will continue expanding dramatically in the future.

Dart: Definitely. I think there’s sort of two camps in video games right now–one that is heading toward ever more realistic and immersive/escapist games, and the other (which I think has developed in large part from the super strong indie game world) is toward creating games purely for fun and finding new ways to engage people through innovative gameplay or devices that offer new types of interactivity. I think Nintendo continues to be the corporate leader in that camp, and the unfortunately ignored Wii U has tons of potential for unique gaming opportunities that I would love to see people explore more. I think while the Wii U offers new ways to play games, other technologies like Oculus Rift and Kinect offer ways to immerse yourself deeper into the game worlds.

I think that technology is awesome too and has tons of potential, but personally I always favor simple and unique game mechanics over extreme realism. I’ve just been playing A Link Between Worlds on the 3DS and I love the mechanic of merging into walls and it’s used so simply and so effectively in all these different ways throughout the game.

I think the games Spike dreamed up for Her are awesome because he could’ve really easily gone down the route of super immersive virtual reality or something, but instead these games seem purely for entertainment, and showcase some really unique worlds and types of gameplay. I also like how the hologram game integrates with social media, like when Theo’s checking messages with Samantha, which I’m sure will continue to become a bigger part of the games we play. I think it’s a really hopeful vision for the future of video games and technology, and personally I would love to play a hologram game like that someday!

For more Her-related viewing checking out our doc that includes some thoughts about love in the modern age:

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: Hyperfocus Games -

Screenshot: YouTube/1980sGamer -

Screenshots: Electronic Arts -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki/Waypoint