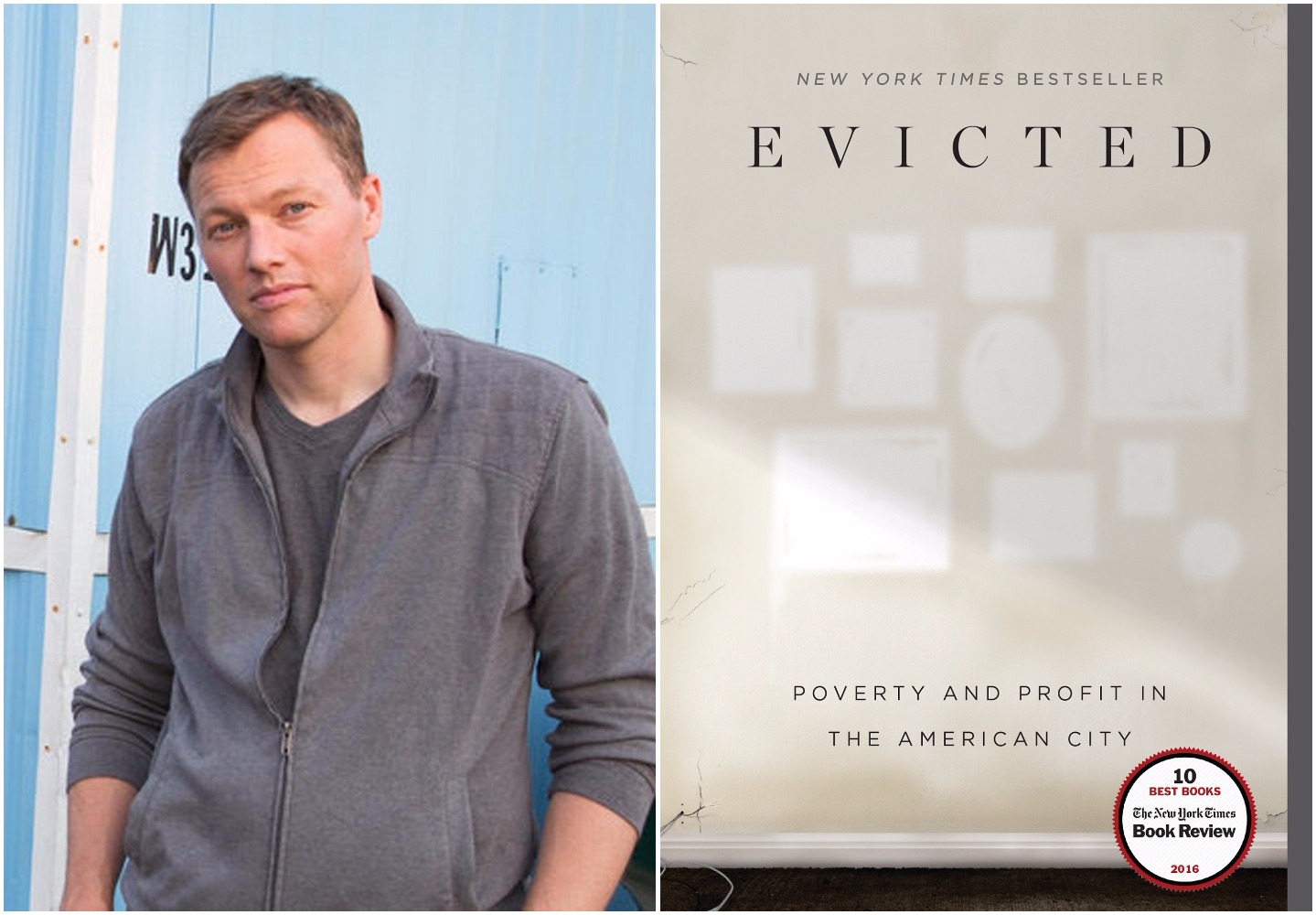

Not since James Agee’s sharecropping epic Let Us Now Praise Famous Men has there been a document as eloquent as Matthew Desmond’s Evicted in its humanization of the working poor. The Harvard ethnographer’s 2016 book begins with Arleen Belle, a single mother of two forcibly moved deeper and deeper into Milwaukee’s bleak inner city after being evicted for a stranger’s damage to her front door, and into a tenuous $550 lease with entrepreneurially minded landlord Sherrena Tarver. We follow both these women’s stories for the duration of a year, picking up six other family narratives along the way.

The result is a Pulitzer Prize–winning, best-selling work of singular insight into the conditions of poverty in the American city, from housing projects to trailer parks, and the human cost of their exploitation. But Desmond has hope, and as I spoke to him over the phone last week, I was struck by his deep empathy for the everyday struggles of Americans on both sides of the housing divide, as well as the concrete solutions he was able to provide.

Videos by VICE

“A universal housing voucher program,” Desmond writes in the epilogue, “would carve a middle path between the landlord’s desire to make a living and the tenant’s desire, simply, to live.” Such a program, already successfully implemented in countries like the UK and the Netherlands, would provide families below a certain income level with vouchers to “live anywhere they wanted, just as families can use food stamps to buy groceries virtually everywhere.” It’s a program that Desmond believes would “change the face of poverty in this country,” more or less eradicating homelessness and making evictions rare.

VICE: What should every renter understand about their rights?

Matthew Desmond: Rights vary from city to city, so getting to know your rights is a matter of knowing where you live, as they can actually be very fair. For example, renters do have the right to withhold rent from their landlords if certain conditions are not met. But rights cost money, so if you’re a renter who is paying 75 percent, 80 percent of your income on housing costs, then you’re going to need a favor from your landlord one of these days. And entering into that kind of relationship with your landlord can put you in a pickle. You see in the book how folks are struggling with the question of “should I talk to her or not,” because while landlords can’t legally retaliate, they can claim more grounds for eviction when their tenants eventually fall behind.

In that case, since conditions are so variable city to city, can the book’s observations about Milwaukee be accurately applied to cities across the country?

More so than not, I think. Milwaukee is a fairly low-cost city, just like a lot of our cities, especially in the middle of the country and in the South. Compared to high-cost cities like New York and DC, where the neighborhoods tend to be a lot more economically diverse, the rights afforded renters in Milwaukee or Baltimore tend to be more elaborate. But ironically, the eviction processes there is often less legislated. One of the reasons I wanted to write about Milwaukee was that if you follow a case like Arleen’s, you have a better shot at representing the situation of renters around the country than you do if you write about San Francisco.

Another tension in your book is the contrast between the trailer parks and the slums. Do you think when we think about poverty we tend to avoid thinking of poor whites?

The thing we tend to think about when we think about where poor folks live is public housing. We picture these giant towers looming in the public imagination. But the opposite is true. Only about one in four families who qualify for any kind of help actually get it. So when we think about a typical poor family today, we should be thinking about people living in the private rental market with zero help from the government and spending most of their income on rental costs.

What I saw is that even though poor whites are certainly struggling a lot and facing massive housing insecurity, they were still able to find properties without being forced to relocate to the north, that being the African American part of the city. This shows us that discrimination in the housing market is still alive and well and that it has a real effect on folks at the very bottom of the market.

One the big surprises of your book is the discovery that slums aren’t actually cheap as compared to middle-class neighborhoods.

I was really surprised by that, too. In a lot of cities in America, it’s not that much cheaper to live in poor neighborhoods than the alternative. So what’s the takeaway? One is that the profits for landlords are higher in poor neighborhoods, for the simple reason that there are fewer expenses or tax burdens, but the same amount of revenue, which tends to reinforce the same trends as far as demographics.

You have a surprising empathy for landlords throughout the book. We come to understand Sherrena’s position pretty intimately, and you even cite the statistic that most renters in Milwaukee think highly of their landlords.

I figured it was my job to paint everyone I met with as much complexity as I was able to. And that goes for landlords, too. We’ve decided to house most of our low-income families in the private rental market. That means the folks on the front lines of providing housing to families of modest means are the landlords. And there are different kinds of landlords, just as there are different kinds of tenants. And I think you see them being generous, sometimes being callous, but it’s a job with high levels of risk. And it’s a job we’re going to need to take very seriously if we’re going to successfully address this problem of scale—

Like the rent certificate programs you advocate in the book?

And vouchers, exactly. I rewrote that part of the book about 30 times because we are bleeding out, and we need a program or way of addressing this problem that is as big as the problem itself. And most places they work pretty darn well. When families receive a voucher and they can spend 30 percent of their income on rent instead of the usual 80, do you know what they do with that money? Study after study tells us that they take it to the grocery store. Their kids become stronger, they move to slightly better neighborhoods, they move a lot less, they avoid homelessness, their kids get to go to the same schools for years in a row. They’re really successful. And so the problem isn’t with the design, it’s with the dosage.

What about the role of screening practices? How do credit ratings and the like wind up making the problem worse?

One of the things landlords in Milwaukee rely on is a program called CCAP, which is an open records database that you can go on to see a tenant’s eviction record. It will show you any small claims they’ve been accountable for, any felonies, even just arrests. So in theory, that allows landlords to weed out tenants that are high risk. But let’s stop think about how those records get generated: If I get arrested, I have a right to an attorney, and if I’m indigent, I have a right to a public attorney. But that’s a right that does not exist in civil court! So most folks that go to eviction court don’t have the right to an attorney or the money to access one, so a lot of people don’t show up. And so, many of these evictions are processed through default. No one shows up, they get evicted, and it shows up online. [It] can really hurt a renter’s life chances. It can prevent them moving into decent neighborhoods. It can keep them accessing from public housing. I think we can strike a better balance by providing landlords with what they need and protecting tenants from this public marketplace of evictions.

How about the issue of domestic abuse, mainly the fact that residents are less likely to call the police because they realize that their homes could be forfeit?

This is something that should give us great pause when we think about what an eviction means on somebody’s record. Because there’s no context behind that information. When I showed the Milwaukee Police Department how every four days a landlord gets a letter that’s domestic violence-related, and that over 80 percent of the time they evict the tenant, they were shocked. They changed the law and, what’s more, the ACLU has since used that statistic to get laws changed in Pennsylvania and mount a campaign called “I Am Not a Nuisance” led by a wonderful lawyer named Sandra Park. And several senators read the book and connected with this issue, 29 of whom signed a letter before the election asking HUD to issue broad guidance to put federal law back on the side of domestic violence survival. And HUD did! So we should be troubled by the fact that these laws exist, but I’m happy to report that this is a tangible policy change that the book helped to effect.

What is the psychological effect of eviction or long-term damage in terms of losing shelter?

My family lost our house when I was in college, before foreclosures were all the rage. It’s quite a thing to have the sheriff knock on your door and then you’re literally homeless within half an hour. Your things are piled up on the sidewalk and your kids are there, it leaves a deep mark. And so what we’ve seen in statistical studies is that moms who are evicted suffer higher rates of depression two years later. It seems to be something the really gets in your skin, or as Arleen put it, “My soul is messed up.” We know that suicides attributed to eviction doubled in a five-year time span where housing costs were going up and that’s a national statistic.

Another statistic you cite is the trend toward demolishing project housing.

This is fascinating because, if you read accounts of people moving into public housing like the Cabrini-Green Homes in Chicago or Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis back when they were built, it’s like a big hotel resort for them. And then 18 years later, they’re destroyed in front of a national audience. Take any program and stop funding it and it’s going to fail. So we initiated the age of the dynamite stick and the wrecking ball, and lost a lot of affordable housing units. The good news is we’ve learned to do public housing in a different way. If you go to DC and say, “Where’s your public housing,” you’ll discover that they’re all over the city. The returns on public housing are really high, so it’s too bad that the latest data from the Public Housing Bureau shows that only six percent of low-income families live in them. And because these units are so desirable, the waiting list is not counted in years, it’s counted in decades.

After having written this book, do you have an answer to how domestic policy should be fixed so that it delivers on the promise of equality rather than depending on the victimization of an underclass?

I think we as a nation want a different conversation about poverty. We want a conversation beyond these stale binaries of “deserving” and “undeserving” poor. We want a conversation that seriously asks why we’re the richest democracy with the worst poverty. What is it about us, about our design? If you ask that question, then I think you can’t get away with just saying “some of us aren’t playing by the rules,” because I think that’s an insufficient answer. And I think that with effect to the issue of housing, it touches so many issues across party lines. If we are a conservative person and we care about keeping families together and stabilizing communities—which is a traditional, conservative ideal—then we have to care about affordable housing, we have to care about allowing families to be stable. We have to then look at educational inequality or health disparity or spending. Because we can either spend on providing more affordable housing or spend on the fallout of denying so many families this fundamental human need.

Recent work by J. W. McCormack appears in Conjunctions, the Culture Trip, the New York Times, and the New Republic.

Evicted by Matthew Desmond is available in bookstores and online from Broadway Books.

More

From VICE

-

Collage by VICE -

Screenshot: TrampolineTales -

Lauren Levis, who died after taking iboga at the Soul Centro retreat in 2024. (Photo courtesy of the Levis family) -

Photo by Noam Galai/Getty Images for Shorty Awards