This story appeared in the September issue of VICE magazine. Click HERE to subscribe.

Nicholas Heyward Sr. stood on the rooftop of 423 Baltic Street, steps from where a cop killed his 13-year-old son in 1994—long before America came to know Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Akai Gurley, or Philando Castile. He looked out over the panorama of Brooklyn around him—the skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan to the northwest, the New York Bay to the south, and miles of Kings County opening out to the east, punctuated by church spires and water towers—before walking me into the stairwell where his son had been shot.

Videos by VICE

Afternoon light poured in from a glass-block window above the landing to the fourteenth floor of the building, one of several in the Gowanus Houses, a public housing complex in the southern part of the borough. Nicholas Naquan Heyward Jr. and three of his friends were playing cops and robbers on the evening of September 27, 1994, when they decided to go downstairs and search for the other boys in the game. They lined up single file, toy guns in hand, and prepared to sneak downstairs.

“When Nicholas turned the corner,” Heyward recounted, “he saw the officer. The officer yelled out [something like], ‘Hey!’… and Nicholas said, ‘We’re only playing, we’re only playing!’” Then there was a bang.

The boy had been shot in the chest by a New York City Housing Authority cop—a black 23-year-old rookie named Brian George, who’d been on the force for only two years. Nicholas was rushed to the hospital for emergency surgery, but it was too late. He died early the next morning.

“No one could have told me when this happened that this officer was not going to be held accountable,” Heyward said, his eyes hazing over. No charges were brought against Nicholas’s shooter, as was the case for most of the more than 2,000 families who lost loved ones to police shootings in the 1990s. Instead, Brooklyn district attorney Charles Hynes framed the killing as a justified homicide, blaming it on Nicholas’s toy gun.

This decision drove Heyward to abandon God and instead invest his faith in an obsessive, decades-long crusade to have his son’s case reopened and reinvestigated. The methods he pursued and the organizations he helped create along the way are a kind of blueprint for the Black Lives Matter movement, its rhetoric, strategy, and culture—so much so that in the years since its emergence, family members of other police-shooting victims have turned to Heyward for guidance. And yet, despite his diligence, and the substantial evidence of wrongdoing that he has collected, the long fight has, until now, yielded nothing.

Now, 22 years after his son’s death, justice appears finally to be within reach. In February, as protests for black lives gathered strength around the country, Brooklyn’s new district attorney, Ken Thompson—the borough’s first black DA—made a highly unusual announcement. He promised to reopen the Nicholas Heyward Jr. case to potentially pursue criminal charges against Officer George and determine whether Hynes or the police committed official misconduct. If George and the city are finally held accountable in this case, it could prove to be a milestone for a movement committed to ending state violence against black Americans, potentially changing the way local prosecutors handle cases of police shootings, and providing closure to Heyward’s long quest for justice.

On the evening that he was shot, Nicholas was playing with friends on the rooftop of 423 Baltic Street, an apartment building in the Gowanus Houses complex, where he lived with his family. All photos by Meron Menghistab

After Nicholas was killed, Heyward Sr. was inundated by stories of police killings of unarmed black people. “Maybe I wasn’t paying attention or something,” suddenly he said. “But I mean, after Nicholas’s death, I just started hearing case [after] case. I was like, Wow, what is going on?”

In 1994, policing was intensifying at the federal level. President Bill Clinton had just signed a major crime bill, sending 100,000 new officers into local police departments around the country. The war on drugs was gaining momentum, and its racially motivated sentencing laws—drugs more likely to be used by minority communities, like crack cocaine, were criminalized at a rate of 100 to one relative to drugs favored by white communities—helped reinforce the already entrenched notion of blackness as criminality. In New York, Police Chief Bill Bratton and Mayor Rudolph Giuliani had begun implementing the “Broken Windows” policing theory, directing law enforcement to focus heavily on low-level crimes on the premise that it would prevent more serious violent crimes. Petty arrests skyrocketed, with a disproportionate number of those stopped being black or Latino.

During the year Nicholas died, the number of civilians shot and killed by the NYPD increased by nearly 35 percent. Police violence became so severe that Amnesty International investigated the police department, finding a “serious problem of police brutality and excessive force.” A year before his death, Nicholas had already experienced this aggressive policing. In October 1993, at age 12, Nicholas was falsely arrested coming out of his building with his parents, his little brother, and his dog. An officer pointed a gun in his face, forced him facedown on the ground, and then dragged him off to the precinct. According to a complaint the family filed with the city’s Civilian Complaint Review Board, the officer who questioned Nicholas said he “would stick [a] gun up his ass and pull the trigger” and “he would be dead by the time he is 15.”

Amid all of this, police officers, including Officer George, were protected by the power US law grants to an officer’s fear. A 1985 Supreme Court decision ruled that police use of deadly force must be “objectively reasonable.” Determining just what is “objectively reasonable” hinges in part on whether a suspect presents an immediate threat to the officer’s safety or the safety of others. As the civil rights attorney Chase Madar has noted, “In actual courtroom practice, ‘objective reasonableness’ has become nearly impossible to tell apart from the subjective snap judgments of panic-fueled police officers.”

Heyward’s allies say that in Nicholas’s case, the DA appears to have gone to great lengths to demonstrate that the shooting fell under this reasonable-fear standard—and the outcome was not unique. No police officer was ever tried for shooting a civilian under Hynes, who held office for a quarter of a century.

Nationally, police kill at least 700 people per year, according to the National Violent Death Reporting System. A Washington Post investigation found that an average of only five officers per year were indicted on felony charges for fatal shootings over the past ten years, and just 11 of the 65 officers charged over the past decade were convicted. It’s hard to tell whether police brutality has worsened or remained constant since Nicholas died in 1994. The federal government does not keep an accurate count of police killings of civilians, and private efforts to tally the deaths inevitably come up short. The national Stolen Lives Project counted more than 2,000 killings by city, county, state, and federal law enforcement and corrections officers between 1990 and 1999. Last year, police killed close to 1,000 people, 90 of them unarmed, according to the Post. Of those who were unarmed, 40 percent were black men, though they make up only six percent of the population.

Nicholas encountered Officer Brian George in the fourteenth floor stairwell. DA Hynes said that the area was dim, but witnesses said it was brightly lit.

At daybreak, when Heyward and his wife, Angela Grant Heyward, returned home from the hospital, their six-year-old son Quentin was still in bed sleeping. When he awoke and realized that his brother wasn’t there, he made him a get-well card. He drew Spider-Man and Superman on the front, and inside wrote: “Get well soon, Nicholas. Come home soon. I miss you. I love you.” When his mother went into his room and told him that Nicholas was gone, his world fell apart. “The way he cried I will never forget,” she said.

Grant Heyward hadn’t been allowed to see her son until he was already under anesthesia on a gurney. Heyward hadn’t seen Nicholas at all before surgery. They waited all night long, thinking their son would be returned to them, broken but alive. But around 3 AM, the doctors told the family that the bullet had done too much damage. Nicholas couldn’t be saved.

The doctors asked if the parents wanted an autopsy performed. They said yes and then went home to his empty room.

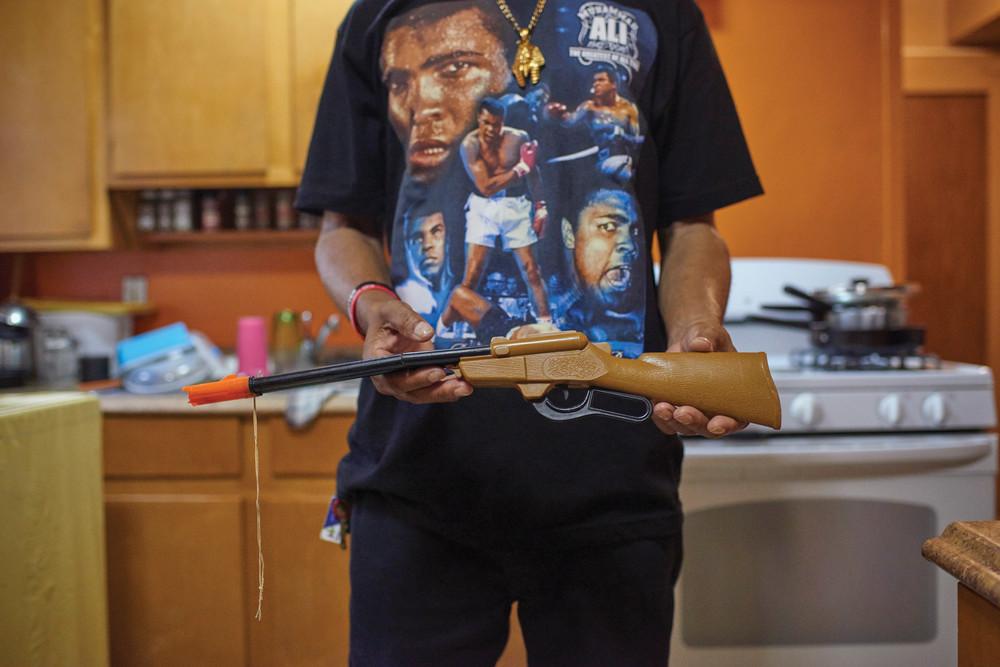

Today, the room is something of a shrine to Nicholas, and it doubles as Heyward’s office. The first time we met, he showed me. Piles of case documents, police reports, newspaper clippings, and family photo albums were stacked on the floor. Protest signs lined the walls: “JUSTICE FOR NICHOLAS HEYWARD JR., JAIL KILLER COPS, JUSTICE FOR TAMIR”—a reference to the shooting of Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old killed by a police officer while he played with a toy gun in a park in Cleveland. Photos of Nicholas as a baby, as an 11-year-old, and as a 12-year-old smiled down from the walls. His toy rifle rested near the door.

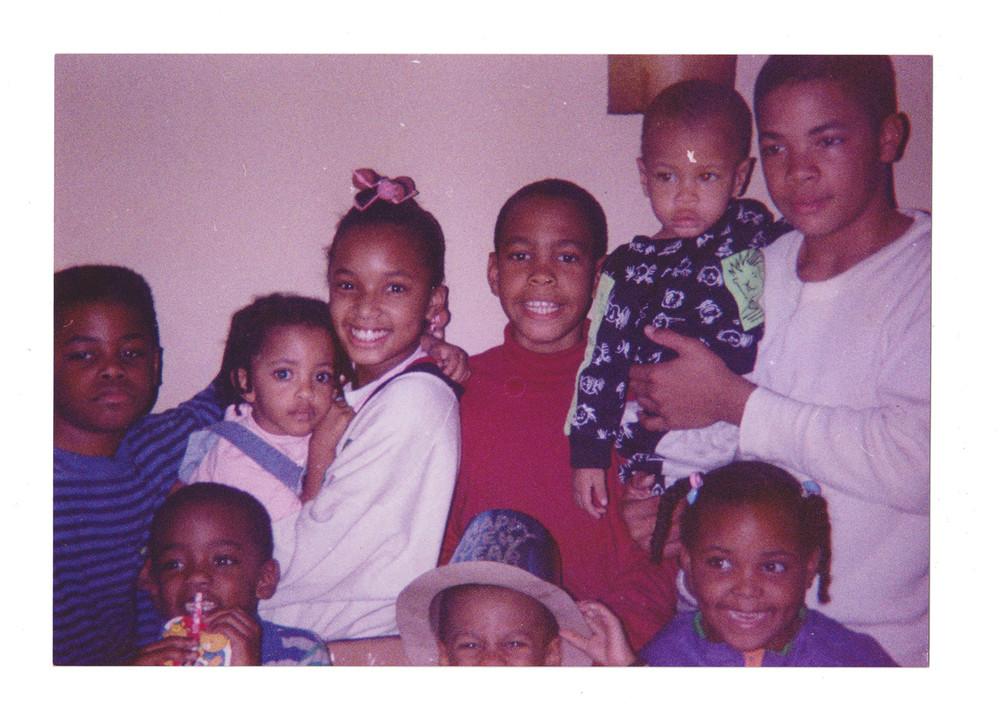

Heyward opened an album full of pictures of his son. As he gently lifted each page, we moved from the day Nicholas was born through birthday parties and weekends with cousins, to newspaper clippings about the shooting and photos from the funeral. What happened in the stairwell seemed written on the 59-year-old’s face—into his gaunt cheeks, his eyes, his mouth that is set and pinched at one corner.

Those few seconds define his life. When Hynes shut down the possibility of criminal charges against George, Heyward filed a civil suit against the city and cycled through four attorneys before reaching a settlement. He and Grant Heyward went on to create a foundation in their son’s name that offers mentoring for children. He petitioned to have the park in the Gowanus Houses complex named after his son. He said he wrote to and met with Hynes’s office several times, bringing new evidence and trying to convince the DA to reopen the case.

Heyward even asked the federal government to investigate the case for potential civil rights violations. The Justice Department declined to conduct its own inquiry, instead reviewing Hynes’s and concluding that it was sufficient. Heyward asked to testify before the city council. He wrote to council members asking them to pressure Hynes to reopen the case, and he wrote to members of Congress requesting they do the same. He tried to meet with Giuliani and Bratton and later Mayor Bill de Blasio, but he said he received no response. He has spoken at public hearings around the city, on Ricki Lake and Geraldo, “in schools, churches, wherever they’ll have me,” he told the New York Daily News in 1998. He conducts regular cop-watch trainings and holds a Day of Remembrance each year on Nicholas’s birthday in late August. Heyward has memorized the details of each NYPD killing since his son’s death and recites them like the prayers of the rosary to anyone who will listen. And he brings the toy gun to police-brutality protests all over the city, recounting again and again the story of his son’s death.

Nicholas, center, age ten, was wrongly arrested when just 12 years old. A police officer told him “he would be dead by the time he is 15.” Photo courtesy of Nicholas Heyward Sr.

Heyward’s singular focus over so many years strained his relationship with his family. Grant Heyward descended into addiction after Nicholas’s death and spent years in and out of rehab. Eventually, after a bitter dispute over the settlement money in the civil case, the two separated, then divorced. Quentin, their youngest son, was left to fend for himself emotionally.

By 2013, Heyward had exhausted nearly every possible remedy in his quest for justice when he found out that Ken Thompson was running to become Brooklyn’s new district attorney. Earlier in his career, as a private attorney, Thompson had helped convince the Justice Department to reinvestigate the 1955 murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till. Looking to court black voters in Brooklyn who live close to trauma like Heyward’s on a daily basis, Thompson stopped by Heyward’s annual Day of Remembrance for Nicholas. He told Heyward that if he were elected, he’d reinvestigate Nicholas’s case, a rare offer from a local prosecutor.

Heyward had already lost faith in electoral politics, but he decided that, given Thompson’s background, this candidate warranted his allegiance. He campaigned for Thompson, leveraging the networks he’d built up over two decades of activism, and in November 2013, Thompson easily defeated Hynes.

***

Twenty-two years ago, when police shot a child, there were no camera phones to capture the horror or social media to transmit it to the world. There was no broad-based national movement to take to the streets and demand accountability. For a while, Heyward felt like he was on his own. For a while, he said, all his efforts felt like preaching into a void. “White people and people in general didn’t believe that police were actually murdering these innocent people,” he said. “It could make you crazy.”

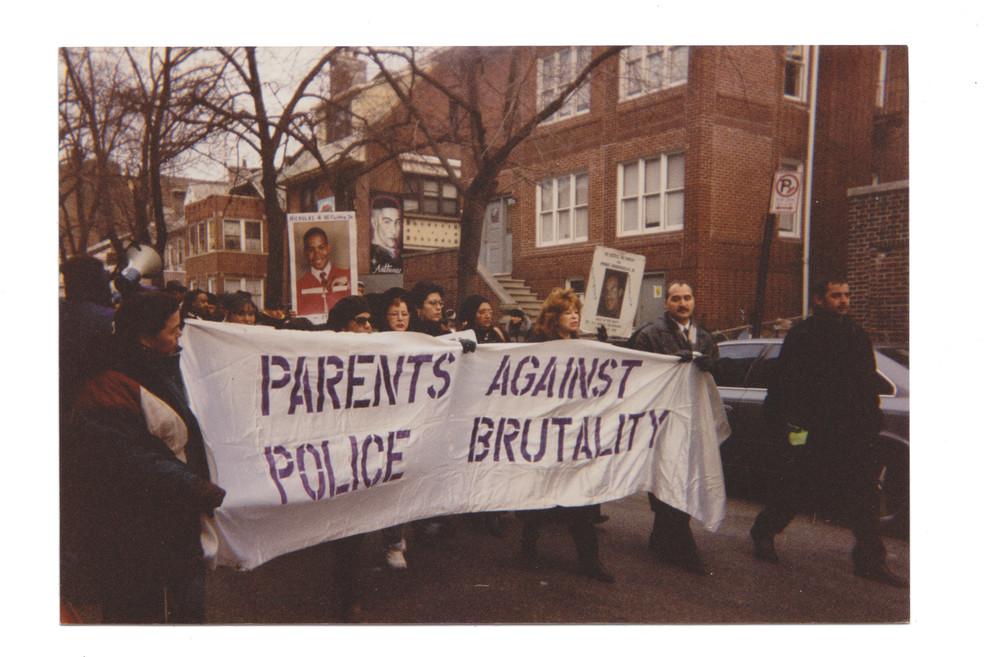

But a couple of years after his son’s death, he became one of the first members of the October 22nd Coalition, which has tracked police killings around the country since 1996, and Parents Against Police Brutality, a group of about 12 victims’ families founded by Iris Baez and Margarita Rosario, mothers of sons slain by the NYPD. Heyward helped build up these early groups, precursors to the Black Lives Matter networks now multiplying around the country. From the beginning, he acted as a mentor to other New York families who had lost sons, brothers, and nieces at the hands of the police.

Heyward has become close with families of victims including, among many others, the mother of Eric Garner, whose death by choking was recorded on a cellphone camera; the relatives of Ramarley Graham, killed in the bathroom of his own home in the Bronx; an aunt of Akai Gurley, shot in 2014 in a housing-project stairwell in circumstances similar to Nicholas’s; and the son of Kenneth Chamberlain, a veteran who was shot to death after his medical-alert system accidentally called 911. He helps these families write letters to elected officials, attends rallies with them, and counsels them on how to cope with the physical toll of sorrow. Akai Gurley’s aunt, Hertencia Petersen, said she met Heyward at a rally a few days after her nephew was killed, and they quickly formed a bond. “I see him as a big brother,” she said, “and he calls me ‘Sis.’ We’ve been working together and supporting each other every chance we get.” Heyward advised her to appeal the judge’s decision in her nephew’s case—the officer was convicted of manslaughter but sentenced to community service instead of jail time. Petersen helps Heyward by reminding him to take care of himself and be mindful of his high blood pressure. “I try to tell him, ‘Sometimes you have to slow down and relax.’”

Heyward also holds workshops on police brutality and has a keen understanding of what police violence against one black person does to all black people. As Khalil Gibran Muhammad, a professor of history, race, and public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School, explained, police brutality affects the black community today the way lynching did in the past. “The problem from a trauma standpoint is that every lynching did tremendous damage to thousands and thousands of people in proximity to that because it reminded them of how low they stood in the social order,” he said. “That’s the lesson that’s still being taught to generations of young black people in this country.”

Kei Williams, a lead community organizer for Black Lives Matter NYC, which has worked with Heyward for two years, said he is instrumental to the current movement. “He’s been at every single rally, every single community meeting,” Williams said to me in August. Heyward protests and marches, usually wearing a variant of the same uniform: a shirt bearing an antipolice-brutality slogan or the image of a black revolutionary, a Black Lives Matter bracelet, perhaps a pin with his son’s face on it, a flat-brimmed hat, and his Malcolm X glasses.

Williams said Heyward brings a sense of history, understanding of the system, and the intimate knowledge of local politics that other organizers lack. Josmar Trujillo, a co-founder of the group New Yorkers Against Bratton and a member of the team pushing the reinvestigation of the Nicholas case agreed. “He’s seen the system, all its ups and downs,” he said. “He has the best perspective of almost anyone that I know.”

“He helped build [this movement],” said Baez, who met Heyward in 1995 at a rally for her son. “Without him being firm and strong like he is, the movement wouldn’t keep going forward. He’s a real warrior.”

Nicholas’s bedroom has become Heyward Sr.’s makeshift office, as well as a sort of memorial for other victims of police brutality. In addition to childhood photos of Nicholas, protest posters that cry for justice cover the walls.

What Heyward has brought to the movement, the movement is bringing back to him, garnering his case more attention and credibility than it received in the past. As Black Lives Matter has educated the American public, “people are more open to believing that the police just lie,” said Roger Wareham, a prominent civil rights attorney who regularly presents the United Nations with evidence of human rights violations faced by people of color in the US and who is advising Heyward in this case.

If there is a conviction or a finding of wrongdoing in the Nicholas case, it could lead to policy changes in local prosecutors’ offices. Marc Fliedner, the former chief of the Brooklyn DA’s Civil Rights Bureau, who was leading the Nicholas investigation until he resigned in early June, said that it’s possible the investigation could expose important flaws in rules and laws governing how the police and prosecutors investigate cases like this, adding that these lessons could set a “tone and precedent” for other jurisdictions around the country.

Perhaps more important, Williams said, a conviction “would give families some type of closure and emotional well-being” and would let activists know “we’re being heard.”

***

The Black Lives Matter movement may have buoyed Nicholas’s case, but it’s likely that evidence suggesting a possible murder cover-up caught Thompson’s attention. Kharey Wood, one of the other kids playing on the roof of the Gowanus Houses that day, said that, as Nicholas rounded the corner in the stairwell, the door on the fourteenth floor opened. Wood said he heard whoever it was say something like, “Hey!” He said he saw Nicholas drop his gun and respond, “We just playing!” Then, Wood said, there was a deafening bang and a flash of red light.

DA Hynes characterized the shooting as a justified killing, and three months after Nicholas’s death, he held a press conference where he laid out his reasons for not pursuing criminal charges against Officer George. He said that the 18-inch toy rifle Nicholas was carrying was “virtually indistinguishable from a real gun.” He stood behind a display of 16 realistic-looking black-and-silver toy guns—some with red tips, some without—instead of displaying only the brown-and-black imitation gun with the bright orange tip that Nicholas’s friends say he had been playing with. He said that George had earlier received two reports of calls from a police dispatcher regarding men with guns in the project, that the lighting in the stairwell was dim, and suggested that George had feared for his life when he saw Nicholas. Pulling the trigger, he implied, was a reasonable response.

It was “abundantly clear,” Hynes said at the time, “that the circumstances leading to the tragic death of this 13-year-old were not the fault of Police Officer Brian George, but rather the result of a proliferation of imitation toy guns.”

Angela Grant Heyward said she was “torn up” by her grief. “When I lost Nicholas, my heart was actually hurting,” Grant Heyward said. “Hurting where I was holding my chest.

But documents in the civil case that Heyward filed against the city, as well as statements from witnesses and several retired NYPD detectives, indicate that Officer George was overly anxious and perhaps poorly trained, and that it is possible he may not have seen a gun—toy or real—in Nicholas’s hands at all.

George was known throughout the Gowanus Houses as “RoboCop,” for his nervous demeanor and his tendency to pull and point his gun at residents at the slightest provocation. A joint pre-trial order in the civil suit lists four witnesses who said that George pulled his gun on residents. Two neighbors, Ramona Hamilton and Ardith Cornelius, told me stories of incidents in the Gowanus Houses in which George grabbed his still-holstered gun for no reason. In one instance, Hamilton and her husband were just walking home from shopping downtown. “We were walking behind him, and as we walked up, he [jumped and] grabbed his gun,” Hamilton said. “My husband said, ‘That cop’s gonna kill somebody.’”

“George was a very afraid person,” she added. “You could see the fear in his face. He had no business out there.”

Graham Weatherspoon, a retired NYPD detective who has advised Heyward on Thompson’s investigation since it began, said that the fact that George had received reports about guns in other buildings before encountering Nicholas that evening was irrelevant. “The only relevant information is what happened there and why it happened there,” Marq Claxton, director of the Black Law Enforcement Alliance and also a retired NYPD detective, told me. “As a police officer, you can’t approach those situations with those preconceived notions of danger around every corner because you will shoot people.” Weatherspoon and Clifton Hollingsworth, another retired NYPD detective, both said that if George had been afraid because of the dispatcher calls, he should have called for backup. And contrary to what Hynes stated, the stairwell had been well lit, according to several witnesses, including Wood, Katrell Fowler, and Rose Marie Rivera—the first neighbor to arrive at the scene.

Fowler, who was playing cops and robbers with Nicholas that evening—he was 14 years old at the time of the shooting—told me that the gun Nicholas was holding that day was not realistic. “His gun was a very, very toy-looking gun,” he said. Gerald Preston, who had also been part of the game, seconded that opinion, adding that “the orange tip of the gun gave it away, period.” But it is possible that George may never have seen a gun in the first place. A joint pre-trial order, a document that is supposed to lay out what both sides agree will be presented at a civil trial, states that Assistant District Attorney Joseph Alexis would testify that George told him that he never saw any gun at the time of the shooting. Alexis, who led the original 1994 investigation into Nicholas’s case, denied via a source that George told him he didn’t see a gun and denied that he would have testified to that fact. The document, a compilation of information separately gathered by Heyward’s and George’s attorneys, was ultimately ruled “deficient” because the judge said it was not “the product of a collaborative effort.” One of Heyward’s lawyers at the time has since died, and the other has no recollection of the case.

A protester, left, holds a sign honoring Nicholas N. Heyward Jr. at a 1997 march on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Photo courtesy of Nicholas Heyward Sr.

DA Thompson has yet to decide whether there is enough evidence to pursue a second-degree murder charge—the only one still applicable—against George, who is now retired. This requires proving intent to kill. The statute of limitations has expired on lesser charges like negligent homicide and manslaughter, but Wareham says that if George was able to fully see Nicholas and had the time to say, “Hey,” this could indicate intent.

In George’s version of events, provided during his deposition in the civil suit several years after the shooting, he said Nicholas jumped down the steps, then jumped back up the steps, then lifted the gun and pointed it. “That’s time to observe, to make an assessment,” Claxton said.

George declined, through a relative, to comment for this story. Neither the NYPD nor the New York City Patrolman’s Benevolent Association, the NYPD’s labor union, responded to requests for comment.

Wareham said that given all the evidence, Hynes—who is currently being investigated for allegations of misuse of public funds—could have made the case for second-degree murder and negligent homicide. “He probably could have gotten any charge he wanted,” Wareham said. “But the DA’s position was: This [case] will go away. It’s a reflection of the same attitude that you find in police departments and law enforcement today: It’s just a black kid.”

Hynes’s lawyer, Sean Haran, says the former DA “stands behind the good and highly professional work that his office performed in investigating and reviewing the matter.”

DA Thompson may be considering criminal charges against George and may also seek to determine whether Hynes or the police department committed any wrongdoing, and Heyward is optimistic that he will; Thompson pursued charges against Peter Liang, the officer who killed Akai Gurley, and he’s overturned roughly 20 wrongful convictions from previous DAs’ tenures. There’s also reason to be skeptical: DA Thompson is the one who recommended the judge not sentence Liang to jail time, resulting in the community service and probation sentence, rendering the case something of a show trial. A spokesperson said the DA’s office is unable to comment on the investigation because it is ongoing.

It’s been a year since the DA reaffirmed his intention to fulfill his campaign pledge. The long wait for closure—for some sort of reasonable response by some level of government to the killing of his child—has only compounded Heyward’s suffering. Now, when the pain comes, it comes in stronger, he said, and he finds himself in tears at unexpected moments. Every time a police officer shoots another black man, he said, “You’re reliving the pain of the loss of your loved one over and over again.”

Heyward holds the toy rifle that he says Nicholas was playing with on the day he was killed.

As ever, Heyward holds out hope. He invited Thompson back to this year’s Day of Remembrance—the annual celebration of Nicholas’s birthday—held on a Saturday afternoon in late August at the Nicholas Naquan Heyward Jr. Park.

This year marked 35 years since his birth and 22 years since his death. As in previous years, there was music and speeches, arts and crafts, basketball games, and a toy-guns-for-books exchange. Thompson did not attend. Still, Heyward told his son’s story to all who gathered and said that he hopes, this time, the DA’s investigation into his son’s death is thorough and transparent.

Toward evening, friends and family members began to say their goodbyes, and the crowd thinned and the plaza quieted. Soon the only sound left was the laughter of the children from the Gowanus Houses playing in the park.

This story appeared in the September issue of VICE magazine. Click HERE to subscribe.

More

From VICE

-

Photo by Stanislavskyi -

Photo by makalex69 -

Lauren Levis, who died after taking iboga at the Soul Centro retreat in 2024. (Photo courtesy of the Levis family) -

Security Footage via WBTV