If you didn’t want somebody to read your parchment scroll, you’d think rolling it up and burning it to a black, charred crisp would do the trick. But you’d be wrong. That wouldn’t do jack. Thanks to science, researchers have been able to virtually unravel a severely burnt 16th century scroll and read the text inside.

A team of scientists at the Cardiff University in Wales have been refining a technique that uses medical imagining to examine delicate ancient scrolls that are too damaged or aged to be handled and unrolled manually. First, they use a CT scan to create thousands of tiny, paper-thin cross section images of the scroll. Then, they feed those images into a computer algorithm that is able to decipher letters, words, and images from each layer.

Videos by VICE

Using this technique, the researchers were able to read a damaged 16th century scroll found in the Diss Heyword manor, in Norwich, England. Inside, they found records about the history of the manor including land deals, disturbances of the peace, and the names of jurors.

The researchers first proved this concept in 2013, using the technology to peek inside a badly water-damaged scroll that was partially stuck together, allowing them to read the text inside for the first time. But this latest example was even more challenging, as the scroll they wanted to read had been burned, and most of the pages were fused together into a charred log.

“The scroll from Diss Heyword was an extremely challenging sample to work with, not least because it contained four sheets of parchment and many touching layers, which can result in text being assigned to the wrong sheets,” Professor Paul Rosin, from Cardiff University’s School of Computer Science and Informatics and principal investigator on this project, said in a press release. “In addition to this, the scroll was heavily discoloured and creased and was covered in soot-like deposits over the entire exterior. Nevertheless, we’ve shown that even with the most challenging of samples, we can successfully draw information from it.”

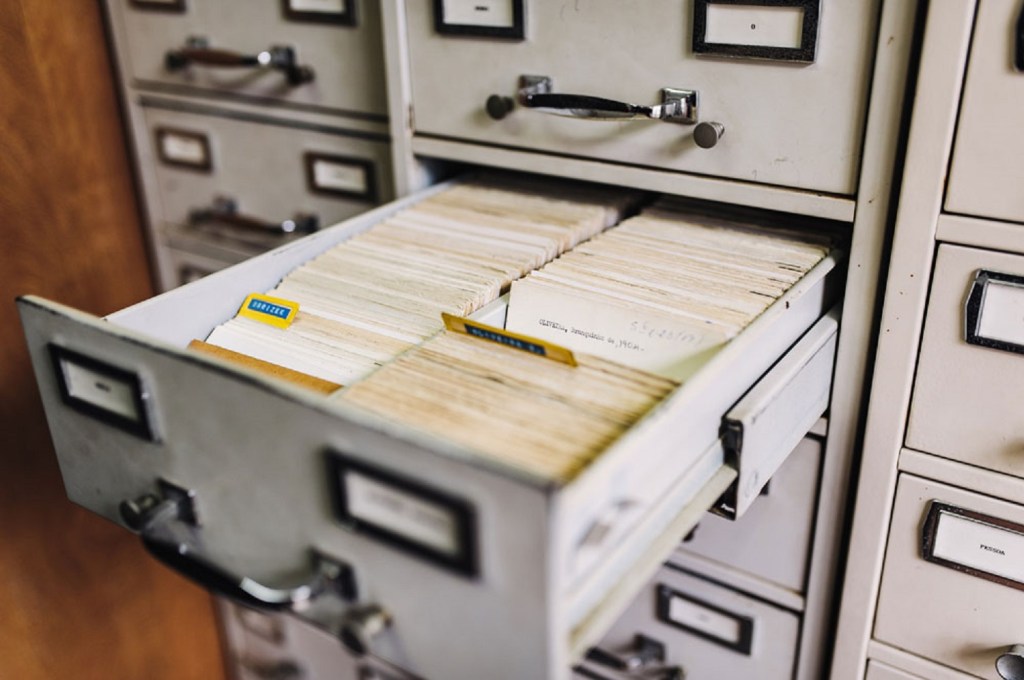

Now, Rosin and his team are soliciting historians and museums around the world to send them their old, unreadable texts for them to peer into with their technology.

“We know that there is a large body of historical documents in museums and archives that are too fragile to be opened or unrolled,” Rosin said. “So we would certainly welcome the opportunity to try out our new techniques.”