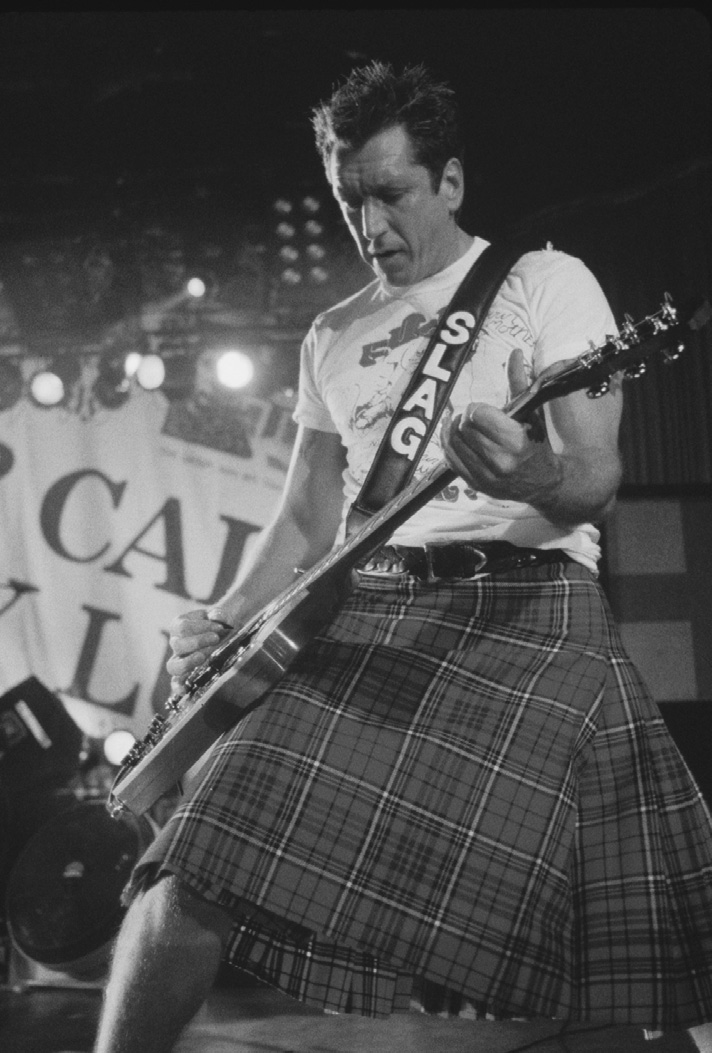

Steve Jones has been a lot of things in his 61 years: a love-starved bastard, smooth criminal, an insatiable man-slut, a master thief, an insufferable prog-rocker, a would-be Yacht Rock A&R rep, SEX shop clerk, Chrissie Hynde’s pre-Pretenders fuck-buddy; a teenage Sex Pistol, a 23-year-old has-been, a sticky-fingered junkie, a shit-hot guitar-slinger-for-hire, Iggy Pop’s muse, a Fabio-haired solo artist, a buff and burnished Hollywood biker, a recovering addict, a childhood sexual abuse survivor, a jailhouse motivational speaker, an ascot’d elder statesman of punk, a beloved LA disc jockey, and—phew—a sexagenarian social media baller. All of which is confessed in absolute unflinching detail, with a nod and a wink and a pinch of Cockney slang, in Lonely Boy (published by Da Capo), his painfully honest, just-published must-read memoir, co-written with Ben Thompson.

Recently we got Mr. Jones on the horn to discuss just a few of the following: Stealing Keith Richards’s favorite coat/Bryan Ferry’s gold record/David Bowie’s bass amp, his cloak of invisibility, his crap childhood, the tens of thousands of “birds” he’s “shagged,” his semi-tragic inability to forge a lasting relationship with a woman, and learning how to read, write and spell after 40. Then there’s a bunch of other stuff like why he can’t stand being in the same room with Johnny Rotten; watching Glen Matlock shag John Cale’s wife; whether or not Sid Vicious kill Nancy Spungen; why Never Mind The Bollocks, Here’s The Sex Pistols is the Dorian Gray of seminal DOA punk rock debuts. We really get into it below.

Videos by VICE

Noisey: Let’s start at the beginning and work our way up to the present. In your pre-Sex Pistols days you were a very prolific and precocious thief. In addition to robbing a lot of unfamous people you also stole Keith Richards’ coat, Bryan Ferry’s gold record, the entire backline of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars in the middle of their infamous two-night farewell concert at the Hammersmith-Odeon in 1973. You refer to your ability to operate largely undetected in the shadows as “The Cloak.”

Steve Jones: The Invisible Cloak, yeah.

Were you really that gifted a criminal? Or were the police so incompetent and security measures so insufficient back in those days?

Well it was that, that’s it. There was no security. No one had cameras. Even alarm systems in stores didn’t work that great. It was the perfect time to be a kleptomaniac for sure, but there was also an element of balls that you had to have. That’s where “The Cloak” came from. I would literally go to any high-end department store up the West End of London—Selfridge’s, Harrods, Hamleys—and work my way into the storeroom and convince myself I was meant to be there. And oftentimes people would actually, people who worked there would see me there, but I had this confidence about me that they wouldn’t even question what I was doing there. And I was like, 12 years old, it was remarkable how many times I did that and got away with it.

So was it as much about the thrill of doing it as it was actually getting free stuff?

It was all about the thrill, to be honest. I mean, it was fine getting some free stuff that I didn’t need, but it was a survival mechanism is what it was. It was, you know, because of the trauma, I guess, if you want to call it that, after my stepfather fucking about with me. After that happened, I didn’t want to be at home, I didn’t feel safe at home. I had this urge on a daily basis to go out into the world and be on a mission. I couldn’t sit still, so that’s why I became a kleptomaniac.

Your fear and anxiety about your fucked up home situation aggravated your ADHD and may have been the root cause of a lot of the antisocial things you were doing in your youth?

It was grim. My upbringing was grim. I had a mother who didn’t really want to have a kid. I had a stepfather who definitely didn’t want me around. Life was good when I was with my Nan, from a very early age to about six or seven. By the time I was about six or seven we moved into this shithole in Shepherd’s Bush in a basement and that’s when the horrible vibes come, you know, and I just hated it. I couldn’t stand it. You know, I was in the way. I was a burden. That’s the feeling I got, you know, and I didn’t want to deal with it.

In the book you make a very frank and courageous admission that you were once molested by your stepfather. What advice would you offer to somebody who went through something similar to that as a child, who is now an adult but is still so consumed with shame and humiliation they can’t really confront it, even now?

I think that happens quite a lot, to be honest with you. I think not one in 100 but maybe one in 50, where some kind of weird shit happens to you as a kid. But the worst is when it happens to you when supposedly you’re in a safe place, at home, with your parents and, I mean, in hindsight the best thing to do is to fucking tell someone because when you’re 10 years old you kind of tell yourself that you had a part in it. You kind of made them do it. You know, and it’s when looking back at it, when you’re 10 years old, how the fuck do you know anything, you know? You’re totally taken advantage of, and the best thing to do is to talk about it. Talk about it one-on-one with someone if you don’t want the whole world to know. It definitely helps because that’s a big burden, that’s a big secret to carry around and it gives you fucking cancer if you ask me and shit like that, you know?

Totally. The truth shall set you free. Jumping back to your early life of crime—The Great David Bowie Heist is just hilarious and blows my mind. There’s this iconic moment in rock n’ roll history and there you are in the background sneaking off with everyone’s shit. For the benefit of readers who haven’t read your book yet could you just give a summary of what happened?

Yeah, I was a massive Bowie fan, specifically a Spiders from Mars fan—as I was Roxy Music, or Rod Stewart and The Faces, or Mott The Hoople. That was my time. When I was a teenager that was what I was obsessed with. Glam rock. Good glam rock, not shit glam rock. I went to what wound up being the farewell concert of Ziggy Stardust & The Spiders from Mars and Hammersmith Odeon where I always used to go and see shows. I used to know that place like the back of my hand, and I went and saw him. I didn’t realize—well no one realized—this was going to be the end of the Spiders from Mars, and they did two nights and after the first night they left all their gear set up on stage, because they were going to play again the next night. The left some guy who was asleep, well he wasn’t meant to be asleep he was meant to be awake looking after the equipment, but he dozed off in about the fifth row and no one else was in this place other than him, me, and my accomplice.

We snuck on the stage started snipping microphones with some pliers, I took the bass amp, I took some of the cymbals. I didn’t take anything from Mick Ronson I don’t know why I didn’t but we loaded up my mini-van that I had at the time, dropped it off somewhere, came back for another round and, about to do some more damage, the guy woke up. He didn’t see me. I saw him starting to wake up and I split. I didn’t realize this was going to be such a big deal. I didn’t realize this was going to be the end of that phase of Bowie. It was on the radio the next morning that all their equipment had been stolen. And of course that made you feel a sense of pride and savor the infamy—”Hey I did that!” Like the arsonist who sets fire to houses and stands outside when the cops show up, watching it burn. Getting kind of like a “Yeah, that’s me! That’s me!” This nobody has made a little bit of a name for himself and no one knows it.

You met Bowie years later, did you ever tell him about this?

I told him about it in a roundabout way. He knew I did it. I mean it was literally nothing, no skin off his nose. But I did make amends to the drummer, Woody Woodmansey. About six months ago he came on my radio show with with [Bowie producer] Tony Visconti. They were doing this Holy Holy tour and they come on my show and I thought: “I’m going to make amends with this guy, but I’m going to do it live and just see what happens.” And I told him when we were on the air. I said, “Listen, I need to make amends with you. I stole your cymbals at the Hammersmith Odeon show.” And he said, “You did? Oh, I didn’t know that.” And I said, “What can I do to make amends to ya?” And he said, “Well, nothing, it’s OK.” And I said, “Let me give you some money, how much you want?” He goes, “Well, give us a hundred bucks.” And I gave him 300 hundred bucks, and he was over the moon. And I felt good for doing it, and I was glad he didn’t get too upset.

So, the story has a relatively happy ending. Speaking of happy endings, you were quite the ladies man. More accurately, you were an Olympic-caliber sexual athlete in your day, maybe you still are. Have you ever counted?

Man, I’ve thought about it every now and again, I don’t know I think I’d give Wilt Chamberlain a run for his money.

He claims to have slept with 20,000 women!

There was a good 10-year period when I got sober—plus there were tons before I got sober when the Pistols were gone. And there as a period when I was, you know, doing heroin and I didn’t do any birds. I don’t know if you know what it’s like when you do heroin but you’re not interested in sex. But when I got off the heroin, when I got clean and sober, I went ballistic. I mean, three a day, you know. Hookers, hot chicks, fucking street people—anything. It was like, I didn’t give a fuck. I had this urge. It was bizarre, it got dark as well, you know. But I have no idea how many I’ve steamed into. But I don’t really do it anymore—not that much anymore.

You also confessed to being a bit of a peeping tom, and there is this one incredible scene in the book where Glenn Matlock is shagging John Cale’s wife in the hotel room next to you and you climb out on the ledge to watch through the window. How many stories up was that?

I would have been like pizza if I fell off the ledge, that for sure.

You explain in the book your youthful habit of using bread, or a hunk of liver, or one time it was an industrial vacuum cleaner, to masturbate. You stress that at the time it was important to get yourself off without using your hands, can you explain that? Did that make it seem less pathetic to you?

I have no idea why I did that, I don’t think it’s any psychological reason, other than I was just experimenting as a kid, as a teenager. Uhh, I mean, you know, people use sexual aids, chicks use fucking dildos to jerk off. I mean it was no different. It was just the device. The bread thing was kind of messy, the best one was the vacuum cleaner cause that’s easy, you just put it on and there’s no cleaning up, you know. The vacuum does it for you.

That was pretty reckless, you had no idea whether or not it was going to rip your dick off when you put it in there right? I mean you were taking a big risk.

[Laughs.] If my cock could talk it wouldn’t be happy with me, I’ll put it that way.

One more question about your love life: in the book blame your dysfunctional relationship with your mother, and what happened with your stepfather for your inability to form a lasting relationship with a woman. You are 61 now, I’m assuming that you’re still single and live by yourself today, and I wanted to ask you, to quote Leonard Cohen, how lonely does it get?

There’s definitely moments where I’m by myself, I could be watching TV, I could be doing whatever, and I think: “What the fuck is wrong with me? Why can’t I have a relationship?” It’s not that I don’t want to have a relationship, it’s more that I can’t have a relationship. I can’t get past a certain barrier, you know. I get to know a chick, she starts to like me, and then it’s all over. And it’s so powerful that I can’t work around it. It’s obviously fear of intimacy, and I just succumb to “OK this is my life. It could be worse, I’m just going to roll with it.” And I’ve been alone all my life and I’ll be honest with you, at this stage of the game I don’t like people over my house. If they start moving shit it drives me insane, I’m so picky.

You also reveal in the book that you were functionally illiterate until the mid-90s, when you were in your early 40s. Then you made a very intensive effort to learn how to read and write, but explain to me what it’s like kind of going through life hiding the fact that you can’t read, bluffing your way through situations that would require you to be able to read, like just even sitting down in a restaurant and ordering off a menu. Can you talk about that a little bit?

It definitely wasn’t good for my self-esteem, not being able to read, or write, or spell. I could barely sign my name, and I still ain’t the best writer. But, you know, most of the good shit that happened to me was after I got clean and sober and wanted to start to better myself, and that was one of the things I thought I needed to do: learn how to read and write. Did wonders for my self esteem. I can read good now, I can spell good, even though spell check sort of does everything for you. It gave me a lot more confidence about myself. And I didn’t freak out whenever that situation where I had to read, write, or spell something came up.

Why would you freak out? Because you would be embarrassed if people found out you couldn’t read?

Yeah I felt like I was stupid.

So you were hiding it, you would just sort of bluff your way through it, right?

Exactly.

It’s kind of a similar experience to being an illegal alien living in another country, which is something else that you did for more than a decade before you got your green card. Given his hardline stance on illegal immigration, I’m just curious what your thoughts are on the election of Donald Trump.

My view on politics, whether it’s Republican or Democrat, I just say it’s Coke or Pepsi. I’m not a real conspiracist but I always believe that all presidents are puppets and they let you believe that you, as an individual, have a say in what goes on in your country and I don’t think that’s the case. I think banks run the show. I think other people in power run the show, and I don’t think it matters who the president is.

Ordinarily, I would totally agree with you but the specific reason I’m asking you though is because he’s made such a big deal about illegal immigration and deporting people, etc. And let’s be frank, it’s a race thing, he’s talking about deporting illegal brown people, not illegal punk rockers living in Los Angeles such as yourself but still, you sort of lived in the shadows. Your immigration status was not legal for quite some time, and there must have been instances where that caused you fear or concern, that you had to swindle your way through something. So when you’re hearing Donald Trump talking about building a wall and throwing people out of the country, did that resonate with you on a personal level?

Well no, not at all. Because, like you say, it’s a race thing. And who fucking knows if this guy is going to do anything he says. Most times they don’t. But to answer you a question though I didn’t start panicking like I’m going to get thrown out of here.

Oh no, no. Just to clarify, then we can move on from this, I wasn’t thinking that you would, because you’re legal you have a green card now, your status is legit. I wasn’t implying that you were worried that Donald Trump was going to deport you, I’m just saying that you could relate to people who might feel that way, that he’s talking about.

I mean, what do you think? Do you think there are a lot of people that just stroll in here, and they’re bad people and they live off the system?

I think that’s a very, very tiny minority of those people. Most come here for a shot at a better life, or because they are fleeing some awful threat of violence or death, etc.

Yeah, I agree. It’s a weird time right now in the world and definitely…

It’s just a way of scapegoating people. You just blame all your problems on brown people from another country that snuck in under the wire and that’s the reason you have a shit job, or why your life sucks, because of brown and black people taking too much welfare, and it works because people don’t want to take responsibility for the miserable life they made for themselves.

It’s been around forever, that one.

Let’s talk about the Pistols. Out of all the classic punk albums, Never Mind The Bollocks has, in my opinion, aged the best. It still sounds completely modern and completely relevant. Do you agree and if so, why do you think that is?

I think the songs are pure. They’re completely pure. We lucked out, getting Chris Thomas to produce it. Most people, most bands back in the day just got some guy who didn’t know what they were doing to produce their record. And we put a lot of time into it, most people think that punk records were done in like a day, you know.

I know you guys worked hard on Never Mind The Bollocks, you did a lot of double tracking of the guitars, a lot of overdubbing. Part of why that album sounds so incredible is that wall of sound, that wall of guitars. Just great, simple riffs that hit you right in the gut. I’ve always said to people, “It’s not really a punk record, it’s just a jacked up rock-and-roll record.

Exactly.

I mean the really punk part of it is Johnny Rotten’s lyrics and his sneering delivery. And the clothes and the bad attitude. But when you strip all that stuff away it’s just a great fucking rock-and-roll record that still fucking rips out of the speakers when you put it on. So my hat is off to you for that sir.

Thank you. I’m glad I had the opportunity to do it and not fuck one thing up, you know.

At another point in the book you also point out that even at the height of the Sex Pistols, and all this talk that punk was killing off all the hippy mustache-rock bands that came before, you would still go home sometimes and play Journey or Boston, which I think the honesty is refreshing and I think also just the fact you never seemed to buy into all this sort of punk orthodoxy about you can’t do this, you can’t do that. I think that’s really refreshing and I respect your honesty about all that.

Well, you like what you like you know. I mean sure, I had to keep it kind of quiet, which was fine back in the day, now I couldn’t give a fuck. But music is funny there is no right or wrong music, it’s just what you personally like. And if you like something, just fucking like it, regardless if you think the band is uncool.

That is how you approach you radio show Jonesy’s Jukebox, correct?

Yes. When I started doing it in 2003, people thought, “Oh here he is, it’s Steve Jones the Sex Pistols he’s got his own radio show all he’s going to be playing is punk.” And no, that’s not what I did, and I did start playing Journey and Boston and people actually got very upset that I was playing that.

Getting back to the Pistols, your relationship with John Lydon, aka Johnny Rotten, is complicated, to put it mildly, at one point in the book you call him a “complete cunt.” You attribute a lot of his anti-social behavior to his insecurity and or alcohol consumption. I’m curious, where does your relationship with him stand today?

We don’t have a relationship. We haven’t spoke since 2008 when we did some Europe shows and festivals—we did like 30 shows and festivals—and it always ends in a fucking disaster. It’s horrible, and I don’t make enough money at the end of the day to put up with him, personally. I just can’t stand being around the guy. You have to act a role and at 61-years old I refuse to do that anymore. To act this role and kiss his ass to keep the ball rolling and it just—there is no relationship. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve got all respect for him, what he did, you know like you say we made a fucking brilliant album, and it was just the four of us before we were famous we made this great record, and there was a period when it was fantastic, a short period, but now it’s just, we drifted apart and it’s all good. I’m all good with it. No animosity towards him, but I’ve no desire to hang out with him and I’m sure he has no desire obviously to hang out with me, which is fine.

You know I saw you guys at the Trump’s casino at Atlantic City back in 2003 and you guys were fucking great, you guys totally smoked.

I remember that gig man, and one of the things I remember thinking was we stayed at that hotel and what a shithole the rooms at that hotel was.

It’s funny you should say that because I vividly remember Lydon sneering, “Donald Trump, your place is a dump!”

Really. What a fucking shithole. Unbelievable.

Last question on that is what, if anything, is the future of the Sex Pistols?

I don’t know. It doesn’t look good, you know. It doesn’t look good as far as if anyone is holding their breath to see us play. I think it’s just better left alone, at this stage of the game. We ain’t even having fun when we do it, it’s purely to make dough, which is why most bands do it but most bands when they go back out on the road they kind of have an agreement with one another that they will get along with each other, that they make it as painless as possible. We don’t have that luxury for some reason—well, it’s not for some reason I just explained to you what the reason is. And it’s a drag. It’s a drag. It’s an easy way to make a bit of bread, but it just don’t look like that’s on the cards.

It’s not really clear in the book, or even most historical accounts that I’ve read about the Sex Pistols, why Glen Matlock was kicked out of the band and replaced with Sid Vicious, can you explain that?

I think Glen wasn’t really one of us, if you will. He was very clean. He was very, uh, I don’t know man. I mean, on one hand we had the chemistry, the four of us came up with all them songs, that chemistry made Never Mind the Bollocks. But I don’t know other than the fact that he was—his mom was upset with the whole thing; he was a little bit off with it. He was always washing his hands, I know I always say that. He was very clean, he was, you know, and I think McLaren saw that he was a weak link visually, you know, and Sid was the other way, the ultimate looking kid.

It was a pain in the ass, don’t get me wrong. A fucking pain in the ass, me trying to show Sid where to put his fingers on a bass. That was the last thing I wanted to be doing when all the craziness really happened after the [infamous swearing on live television incident on the] Bill Grundy Show. It went into warp speed after the Bill Grundy show. And for me to be trying to show Sid where to put his fingers was a pain in the ass but, in hindsight, it was the ultimate look. The two of them together — Sid and Johnny.

Absolutely. And you guys played a lot of gigs before the Grundy thing and it sounds to me like you guys were a well-oiled machine at that point. You guys go on and the Grundy thing happens and all of a sudden, you know, you’re just super famous, and all eyes are on you, and Glen is out and Sid is in but you no longer have this band that’s this killer live thing right?

Yeah it was uh, it was uh- it fucked things up. I think that was the beginning of the end. That was the beginning of the end, the Bill Grundy Show. As great as it was as far as publicity, fame, and household names overnight, it was the beginning of the end too, so it was kind of, what do you call it, a double-edged sword I suppose.

You describe Sid as basically a sweet-natured, intelligent person who quickly started to believe his own hype and kind of became trapped in the persona of Sid and the expectation of 24-7 anarchy and disruption and “punk rock behavior,” which ultimately lead him down the path of self-destruction. You write that ‘If we called him “Sid Kind” or “Sid Gentle” it might have gone differently.” Does it bother you that the public perception of who he was is so different from the person that you actually knew?

At the time, it was so crazy. Everyone had their own shit to deal with. It was just such a crazy time. Too much too soon, and it got kind of dark, and especially when we came to America, that’s when it was clear to me that I couldn’t handle this anymore. “Right, I’m fucking off.” At the time it seemed like the logical thing to do. It was my best thinking at the time, just to fuck off. In hindsight, maybe we should have huddled around and talked about it but it just, it just, I couldn’t handle it. I couldn’t handle it.

In the book, you confess, more or less, that you pissed on Elvis’ grave at Graceland, how does it get to that point?

I was in a haze. I was told I did it. I don’t remember.

I love how you end that story by saying “At least I didn’t shit on his grave,” which I think is also a very Sex Pistols response to things. One last question about Sid: You don’t really offer up your take on what happened that infamous night at the Chelsea hotel so let me ask you directly. Do you think that Sid Vicious killed Nancy Spungen?

I have no idea. I really have no idea. I didn’t speak to Sid after the band kind of split and he fucked off to New York. I didn’t really have any contact with him, so even though I was in a band with him but that really didn’t give me any insight into what really happened. I’m just as clueless as anyone else.

So, post-Pistols you hit bottom, your heroin habit spirals out of control. You’re living in New York City with this woman, and to make money to feed your habit you’re reduced to stealing from women’s purses at nightclubs, or selling old promotional rock band photos of band’s like Heart on the street. What a dizzying turn around. From being at the center of the pop cultural universe six months before that to robbing people to buy drugs. Did you kind of feel like you’ve been chewed up and spit out by the pop culture machinery?

Definitely like, that was the feeling like, ‘What the fuck happened? Where are our people now?’ No one gave a fuck. There was a good period of time where the Sex Pistols were uncool. Now it was about New Wave and nobody gave a flying fuck about punk rock, or Sex Pistols. But for some reason, and God knows why, now it just seems to be part of culture.

So back to the present, you’ve become a big-time DJ in Los Angeles, you just published an this memoir and you’re a gas on social media. Your Instagram account is hilarious, it’s like a one man Benny Hill Show.

I just love it. You get a minute now you used to get 15 seconds on Instagram, so you can make a bit more of it. I get a whim, and I have an idea, and I have all of this shit at my house. I’ve got tons of wigs and masks, and stuff. It’s a relaxed environment so you’re totally relaxed and I’m by myself you know, there’s no pressure and you just come up with some great stuff. You just set the camera up and let it roll, and just do a few takes and whatever and hey presto you got and you get some funny stuff—as long as you’re funny, that is. I’d love to turn it into some kind of TV show.

Lonely Boy is out via De Capo Press now.

Jonathan Valania is the Editor-in-Chief of Phawker.com

More

From VICE

-

Gonin/Getty Images -

Illustration by Reesa. -

Screenshots: Sega, Nintendo, Square Enix -

Screenshot: Team17