I first discovered the horror of African prisons in 2006, when I traveled to Rwanda to document sites of genocide. It was a horrifying task in itself—I photographed rooms full of bones and blood-soaked clothes that stank of death, and belongings still piled against walls that had seen unimaginable horrors. 2006 also marked the first time the Democratic Republic of Congo had held multiparty elections since the 60s, and since I was only a couple of days drive away, I decided to try and cover the election on the ground.

I found a local journalist and interpreter, rented a fucked up Toyota Corolla, and headed for Congo. We weren’t even over the border when we started seeing pickup trucks crammed with child soldiers. Conflict is inherent to Congo. Years of outright war have evolved into ongoing militia conflicts, and one of the weapons used is the HIV virus, spread by squadrons of infected soldiers tasked with the mass rape of whole villages—girls and female babies included.

Once I was in Congo, I’d only been taking pictures for a couple of hours when a policeman started yelling at us. His crazy red and green helmet made him a comic figure hard to take seriously, but before long we had several machine guns pointing at us. We were pushed into the back of a pickup and driven to the police station, which was befitting of a warzone—surrounded by high walls of corrugated metal with watchtowers on the corners.

The journalist told me the bad news: They wanted $20,000 for our release. This was not an option, and we were separated and pushed into cells. Then the long wait began. Alone in my cell, the fear was indescribable. There was no diplomatic mission in this part of Congo. No one knew we were there, and no one cared. Possible future scenarios played out in my mind, and they were all pretty bleak.

After several hours I heard a car horn and as I looked out of the cell a pristine white Range Rover pulled into the compound. We’d been unbelievably lucky. Our interpreter, a girl we’d picked up randomly, was having an affair with a Congolese government minister and had pulled a few strings. After some more shouting, we were released and issued a ticket du liberation on a Post-it note, signed by the minister and the chief of police.

We’d been saved on a whim, but the very serendipity of our liberation hammered home a shocking lesson: More often than not, the people being held in these godforsaken places are as innocent as I was.

Guards outside the main entrance of the Ruyigi district prison, Burundi.

Videos by VICE

Burundi, a tiny country in the heart of Africa, is one of the world’s poorest nations, and is emerging from an ethnic-based civil war that has lasted 12 years. The war has been going on so long in Burundi that few can remember what it was like before. Generations have been swallowed by it. Most young men become soldiers when they are children and have no idea where they’re from, let alone where to go back to.

This devastating situation has bred a generation of career rebels and soldiers. They have no instinct to return to their homes and families when the war is over. They continue to fight—and find reasons to fight—because they know no other life.

These bandits, fueled by banana beer, regularly climb into pickups and drive down the main street in the center of Ruyigi, a city in the east of Burundi, randomly throwing grenades into open bars where they suspect soldiers to be drinking. The result is carnage.

Amid this chaos sits the prison; A blank, ramshackle brick building with rusting gates. After several futile attempts, I finally managed to get access and was invited into the governor’s office—a dingy room stacked to the ceiling with papers. Behind his rough desk, hacked from local dark mahogany, beamed the largest poster of Barack Obama I had ever seen. I wondered if America’s first black president had any idea that places like this existed.

The governor greeted me with a broad but nervous smile. He was keen to share the problems the prison faced with the outside world. He knew it was the only way anything would change. A week later I was informed that he had been sacked for allowing me access.

Prisoner looking out of the main gates of the Ruyigi district prison, Burundi.

He told me there had recently been riots, and that no food had been able to enter the prison for some days (generally in African prisons the families of prisoners are responsible for supplying their food). The prisoners were hungry, and hungry meant dangerous—the anger and frustration was causing them to fight, and sometimes even kill each other.

I knew from my research that the prison was operating at 270 percent capacity. When the doors to the prison opened, that bloated number became personified. The uncovered courtyard seethed with bodies—men, women, and children. Prisoners were so crammed in they couldn’t all lie down at the same time. Ramshackle shelters around the perimeter offered minimal protection from the elements. And it rains a lot in Burundi.

The smell of the place was overwhelming—the riots meant lockdown, so no one had been allowed in or out and the toilet pits were overflowing.

The place fell silent while hungry eyes looked us over. They don’t get many visitors here. As instructed, I’d taken everything out of my pockets and left it in the car, but as we walked through the crowd I could feel cold, rough hands furtively pawing at my clothing.

The governor and two guards with AK47s guided us through the crowd into a small room at the back of the prison, where the children were kept.

The female prisoners at the Ruyigi district prison, Burundi, are not properly separated from their male cohabitants and are subsequently raped regularly, which leads to many unwanted births and high rates of HIV.

Children are in these prisons for lots of reasons, even though, by law, no child under 15 should be incarcerated. Some of them are born in prison—the unfortunate offspring of raped female inmates. Others, shockingly, are accused of petty crimes as revenge in neighborly disputes or family arguments. That’s one of the less charming aspects of Burundian culture. These children do, however, have something in common—none of them have seen a courtroom, and are detained arbitrarily and without trial.

The lack of a juvenile justice system also entails that children older than 15 are being tried as adults. Burundi has only 106 lawyers to cater to a population of more than eight million, and was declared east Africa’s most corrupt country in 2010. The prisoners here regularly wait more than four years to get a trial. Judges require a bribe to conduct the proceedings and the more you pay, the more favorable the outcome is. Rural families are unlikely to have the money to cover the bribes, and so are unlikely to ever free their relatives from prison.

Earlier, while I was staying in my rundown hotel, I was approached by a drunk judge enjoying the free booze on a training program. He wanted me to give him my phone. I asked him why and was met with a confused look. “Just give me something, then,” he said with a frown, “anything.”

The women’s section of the prison was separated from the rest by one unlocked door. We heard stories of how the women are regularly raped by the male prisoners, and subsequently infected with HIV.

Anyone coming from a developed country would find it tough living in the best hotel in Burundi, so I don’t think I can really explain just how shitty life is for these prisoners. When the outside is a place where bandits are randomly throwing grenades into bars, and there’s no food, and your children are dying of AIDS or becoming child soldiers, the inside has to be absolute hell.

The man from Tanzania

Most of the prisoners spoke only Kirundi, their local dialect, so I couldn’t talk to them much. But one man in solitary confinement was from Tanzania, and he spoke some English. I attempted an interview. He told me there had been no food in the prison for two days, and that they were starving. He begged me for help. I said I would try to tell people what was going on, so that help could be sent. He broke down in tears. These are people at the end of the line, in a country where the line is as long as it gets.

Find Thomas Martin at MartinAndMartin.eu.

The prison’s main courtyard was overcrowded with hungry inmates.

Child Prisoners, Ruyigi district prison, Burundi

Young prisoners striking a pose in the Ruyigi prison’s main courtyard.

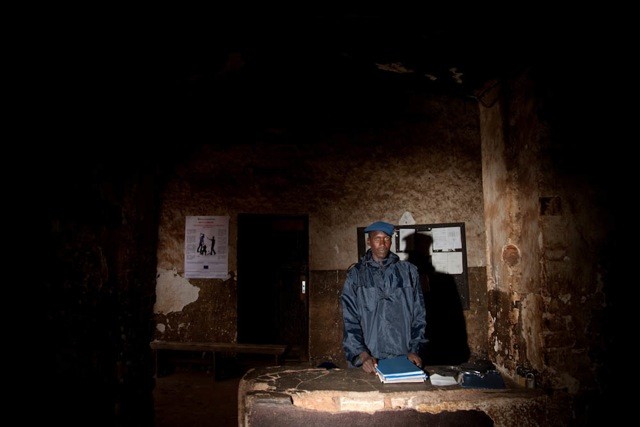

This photo was taken at the Gitega prison in the previous capital of Burundi. The guard had just told me I wasn’t allowed inside the walls.

Prisoner and guard outside the main entrance of the Ruyigi district prison, Burundi.

More

From VICE

-

aydinmutlu/Getty Images -

Screenshot: Metavision Studios -

Photo: Annette Birschel/picture alliance via Getty Images -

All photographs by Adam Rouhana