“Violence, motorcycles, and gangbangs” was the gothic motto emblazoned on the back of jumpers lining up for our National Run party. Our clubhouse was fitted with an industrial strobe light that flickered behind two blonde strippers twirling around a pole. The flashes made the girls look like they were dancing in slow motion and the drifting fifty dollar notes appeared frozen in mid-air.

Speakers that once blared Creedence Clearwater Revival were now pumping “Gangster’s Paradise” by Coolio. And the old guys were getting into it, bopping their heads and dancing with slurring pub-conditioned moves. The heavy reverb from the bass combined with the amount of THC in my system had a hypnotising effect. Another member turned to me, his diamond grillz shimmering. “Where the fuck would you rather be?” he yelled as he threw more cash toward the girls, his eyes pinned on the floating money.

Videos by VICE

Sadly, nowadays these scenes are quite rare. Between the Government’s biker witch hunt, and the mainstream appropriation of bikie fashion, the last true-blue Australian counterculture is just about dead. The sun has set on the Nike Bikies.

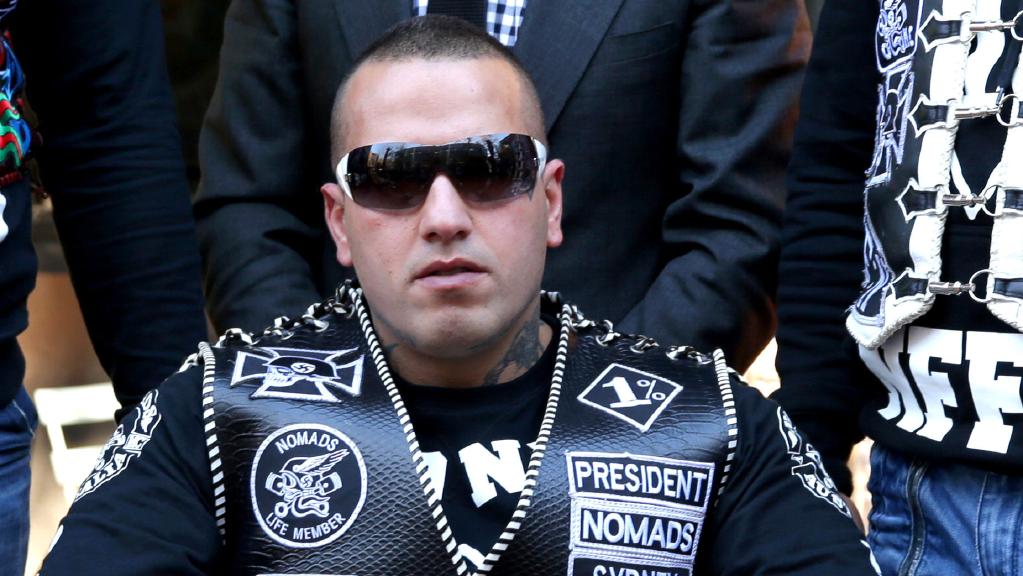

The term “Nike Bikie” originally referred to Middle Eastern bikers in New South Wales. Those of us who took the fashion of the Western Suburbs and melded it with biker culture, gave birth to an undeniably Australian image. Our lot brandished gold chains, clean cut mohawks, and drank litres of Red Bull. Most of us wore Cipo & Baxx jeans that fit a little baggier than the classic Levis, and were excessively fashioned with pockets, patches, and diamantes. Sunglasses were either Versace or Burberry Sport. Cologne of choice was Creed’s Aventus. And the bum-bags were Gucci or Louis Vuitton—a bougie improvement from the classic Adidas waist bag from Footlocker. But the most important touch was the infamous Nike Air Max TN. Everyone wore Nikes, whether they were Shox, TNs, or Air Maxes, and the Nikes become the uniform of the new wave of Australian bikers.

The image made us all think about where we came from. There was a migrant feel to the aesthetic, even though some of the brands are considered high fashion, to us they were the commodities of suburban dreamers. The stuff you would hear your favourite rappers talk about or see the movie stars wearing. It was a very different vibe when compared to what the old school bikers stood for—a lifestyle that was as much about being reckless with the law as it was about being reckless with your self.

When I became a patched member, biker culture was at a crossroads. I was 23 on my first national run and we travelled up to NSW from Melbourne. The sun wasn’t doing us any favours as we stormed up the highway in heavy jeans and leather vests. Along the way we met old school bikers from country towns with long hair, beer bellies, steel cap boots, and faded patches. They looked at us suspiciously because they too understood the drift between themselves and the new guard.

On this run we were all bikers, but the old guys understood there was a cultural division between young and old that was about more than age.

When I was about eight I remember going with my Dad to have our car serviced in Oakleigh. A member of the Gypsy Jokers rode into the shop and started yelling at the mechanic. My dad panicked and we quickly rushed to the safety of our RAV4, but the Joker’s brand new Softail had blocked us in. The biker was wearing a blue wife-beater beneath his colours, and we were forced to watch as he picked up a wrench and clobbered the mechanic’s face in.

Mum asked my old man why he didn’t call the cops, and he replied as if the answer was obvious. The image of the biker staring him down as he saddled up on his Harley was terrifying. He was scared and those guys didn’t give a fuck about the cops. And that’s because in the 90s, outlaw culture was a different game. The violence and attitude were centre stage, while the fashion, drugs, and partying were on the periphery. But somewhere in the late 2000s the culture went inside out.

In many ways I attribute the rise and eventual dominance of Nike Bikies to the Gold Coast scene. There, bikies had always been more about glamour, but the image wasn’t widely known. In films, TV shows, and dated news reports we used to just see the old guys. Nike Bikies were just about invisible, and us migrant kids with bikes felt like the minority. But in 2006 the shit hit the fan in Queensland, and suddenly Nike Bikies were everywhere.

The infamous “Ballroom Blitz,” was a brawl at a Queensland boxing event between our club and The Hells Angels. The fight left five of their members in hospital and won us the reputation of the most violent club in Australia, embraced by the club motto “violence with attitude.” That incident, along with the Broadbeach Brawl, where an alleged associate of our club was involved in a brawl with 18 Bandidos, led us to be the first outlaw motorcycle club in Australia to be declared a criminal organisation.

Suddenly the nightly TV news was all about Queensland’s Nike Bikies, and in the eyes of the general public, as well as the older patched members, we had become a force to be reckoned with. It was kind of empowering, but it came at a serious cost.

In 2013 Queensland Parliament imposed the Vicious Lawless Association Disestablishment Act, known as the VLAD laws, which were enacted to “come down harshly on outlaw motorcycle gangs and their members.”

Suddenly members or associates of outlaw motorcycle clubs who were convicted of a serious crime would have to serve an extra 15 to 25 years on top of any prison sentence unless they disclosed information about their club. The laws banned public meetings of more than two members in public. Club colours and outlaw biker insignia were also banned from being worn in public. The government was trying to strip us of the only identity we had.

The event was like the crucifixion of all biker subcultures in Australia. Everyone was forced to make sacrifices. Members were selling their bikes and putting up their homes to help fight the legal battle in the High Court. The whole thing really separated the boys from the men and made us question what we were fighting for. The answer, of course, is that we were fighting for our place in society.

Biker clubs serve a function that general society doesn’t recognise or accommodate. For anyone feeling left behind—but unable to relate with schools, rehab, welfare programs, or offices—it provides a sense of purpose.

Becoming a member begins by prospecting for a club. This is a year-long vetting process and journey that unpacks who you are and what it is you want to become. When I joined the club, they helped me curb a spiralling drug addiction. There was a support network that kept members active with odd jobs and social runs. It felt like I had been given my life back, away from crack houses and nights spent pressing buttons at the pokies. Suddenly I was on the highway rolling around barren terrains with nothing but the road, the roar, and our thoughts. Their was a purifying quality to it all, the way a motorcycle speeds into the hazy distance, watching the world dissolve as you grapple with the violent turbulence of moving forward.

But around the time I was finding my feet, the outlaw community was being persecuted and it was taking its toll. After Queensland’s VLAD laws were put into effect, along with the media campaigns portraying Nike Bikies as Australia’s public enemy number one, more and more people came after us. This eroded our freedoms for obvious reasons, but another shift was taking place and it was just as damaging.

As Sons of Anarchy appeared on television and fake Harley Davidson sweaters appeared online some sections of the public began to romanticise our culture. On the outskirts, the subculture had become mainstream and the image had become obscured. It was harder to tell who was actually a bikie and who just dressed like one.

Nowadays, bikers who are heavily persecuted have had to step down or out of the spotlight. The interstate runs are fewer due to the varying laws between states that restrict riding in groups while “flying colours.” More than two members aren’t allowed to drink at the pub because it’s considered “consorting.” There’s now a prison in Woodford exclusively for bikers. It all just feels like the best years are in the rear-view.

Last Saturday, while I was at the market helping my dad pack up his stall, a group of Bandidos began shouting at another stall holder. They flipped his tables over and hurled a stern physical warning. Curious, I wandered over to the scared merchant to see what the fuss was about. He told me they were angry because he was selling Sons Of Anarchy patches and vests. He didn’t mind though because he was having trouble selling them anyway.

As I watched him put the remaining patches back in his van and the Bandidos waltz away with their pride, I began to think it was all a bit sad. Is this what it had come to? I guess they were defending their identity from any more bastardisation. It wasn’t just the government stripping them of their image anymore. It was everyone capitalising on it, obscuring it, diluting it. The government and media had successfully stripped the subculture of its honour and they were now refusing to let go of something that was no longer theirs. Nike Bikies have become a blimp in the fog. And to me that’s a tragedy.

Follow Mahmood on Instagram