Morten Strøksnes’s Shark Drunk: The Art of Catching a Large Shark from a Tiny Rubber Dinghy in a Big Ocean is exactly what its gleefully overlong title suggests: a humorously quixotic expedition to hook the astonishing Greenland shark, the longest-living vertebrate around, measuring up to 24 feet in length and weighing over a ton. (Also, its meat can you get you seriously wasted.) But Shark Drunk, which was published this week, is about much more than that. By turns earthy, philosophical, and quietly antic, Strøksnes glides through a range of topics, including sperm whales, literature, sperm whales in literature (à la Melville), natural history, biology, and the mysteries of human nature. Translated from the Norwegian by Tiina Nunnally, Shark Drunk is sure-footed, knowledgable, and absorbing.

In this exclusive excerpt from the book, Strøksnes, a journalist and writer, and his friend Hugo Aasjord, an eccentric artist, have their first tense encounter with the near-mythic creature, whose strength and sheer size threatens to sink not only their salty hopes, but their “tiny rubber dinghy” as well.

Videos by VICE

—James Yeh, culture editor

Summer

The next morning we haul out a couple of crab pots and a long fishing line with dozens of hooks. It’s just as warm and calm as it was yesterday, and the dog days of summer (July 23 to August 23) have just begun. We can already sense it. Seaweed has detached from the sea floor and is now quite visible as it floats in the water. That’s how the ocean regenerates.

Dead bodies that have lain on the bottom also have a tendency to rise to the surface at this time. The sea gives up its dead, as it says in Revelation 20:13. In the old days, people believed food spoiled easier when the dog days set in and that the flies were more numerous and insistent. The sea reaches its warmest temperature during the dog days. The algae bloom depletes the sea floor of nutrients and oxygen, and many jellyfish appear in the ocean. They swim or drift around, pale and yellow, like fringed moons.

As we set out the crab pots, we know they will be filled with brown crabs when we come back to get them in the evening. But are the crabs safe to eat? The level of the heavy metal cadmium is so high that the health authorities have issued a warning. We discover later that two of the crabs have ugly black patches on their shells, no doubt caused by some contagious disease. Hugo also tells me that in the past ten years very few wolffish have been caught. At first he thought it was being fished farther out to sea, in the wintertime. But on those occasions when he did catch wolffish, he noticed many of them had abscesses that looked like cancerous sores. Today the wolffish is making a comeback, though no one knows exactly why.

The sea in Vestfjorden seems cleaner than in most other places in the world. The ocean is deep, the current strong, and huge masses of water are recirculated each day. But there are more heavy metals in this area than farther south, maybe because the sea is like a giant organism, and these open waters are directly linked to the global system of currents, many of which are northbound.

Watch on Motherboard: ‘Surrounded: Island of the Sharks’:

At last we’re going to put out our baited fishing line, five nautical miles south of the Skrova lighthouse. Hugo stays as far away as he can possibly get in our small boat as I cut open the remaining sack of offal from the slaughtered bull. The corpse stench pours out of the bag to hover over Vestfjorden. If we’re lucky, we won’t have a Greenland shark jumping into the boat while I’m attaching a hip joint covered with rotting red meat to the big, shiny hook. I don’t know what sort of expectations the Scottish Highland bull may have had, but I’m pretty sure the animal never imagined anything like this.

We make sure we’re positioned in exactly the same spot as yesterday when we sank our chum bait to lure the shark. Then I drop the hook over the side. As Rimbaud put it: “Hideous strands at the end of brown gulfs / Where giant serpents devoured by bedbugs / Fall down from gnarled trees with black scent!” I let the chain and the line run down to the bottom, not stopping until the reel is almost empty, which means we’ve let out close to 1,100 feet of line. The 20 feet of chain at the bottom are essential because if the Greenland shark bites, it will start to roll around. The skin of the shark is so rough that a chain is the only thing that will hold. If you were to stroke a Greenland shark away from the direction it swims, its skin would feel smooth and frictionless. But if you stroke it in the opposite direction, you would cut your hand badly, because the shark’s skin is covered with tiny “skin teeth,” sharp as razors. Before World War II, Greenland sharks were exported to Germany, where the skin was used for sandpaper. The liver of the shark was boiled, and the fat was used in the production of glycerin and nitroglycerin. The latter, a highly unstable explosive, would often go off accidentally when sparked by small shocks or friction, and kill the people who handled or transported it.

Finally Hugo fastens the line to our biggest float and tosses it into the water. The float is now transformed into a fishing bob, which is something I often used as a boy. But back then I was fishing for perch, brown trout, or arctic char—fish that weighed a pound at most. The bob was the size of a matchbox. You might say we’re still using the same sort of gear, but now we’ve grown up, and we’re fishing for Greenland shark with a bob that measures a yard across. And instead of a worm on a half-inch hook, we’re using a hook that looks like something used in a slaughterhouse, with parts of a huge dead beast attached to it. But that’s what we need. Even a Greenland shark won’t be able to pull the float under, at least not for more than a second at a time.

Wanted: one medium-sized Greenland shark, ten to 15 feet in length and weighing about 1,300 pounds. Latin name: Blunt, rounded snout, cigar-shaped body, relatively small fins. Gives birth to live offspring. Lives in the North Atlantic and even swims under the floating ice cap at the North Pole. Prefers temperatures close to freezing but can also tolerate warmer water. Can dive to a depth of 4,000 feet or more. The teeth in its lower jaw are as small as a saw blade’s. The teeth in the upper jaw are equally sharp but significantly bigger, and are used to bore into the prey while the lower teeth saw their way through. In addition to saw-blade teeth, it has, like a few other types of shark, suctioning lips that “glue” larger prey to its mouth while chewing. And every mating act is violent. On the bright side, the Greenland shark does not have sex until it’s about 150 years old.

Scientists who have examined the stomach contents of Greenland sharks have encountered many surprises. How is it possible that in Greenland, Fridtjof Nansen (1861–1930), the famed Norwegian scientist, explorer, and politician, opened the stomach of a shark he’d caught and found a whole seal, eight large cods, a ling four feet long, a big halibut head, and several chunks of whale blubber? Nansen claimed, by the way, that the shark was able to live for several days even after this “huge, ugly animal” had been cut open and placed on ice.

The eye parasite Ommatokoita elongata, which is about two inches long, slowly devours the cornea of the Greenland shark, until it goes blind. In the folds of its belly the shark also has other parasites in the form of little yellow crabs (Aega arctica). Old shark fishermen have recounted how the parasites would fall off by the hundreds when the shark was hoisted aboard.

Have you ever tried to haul up from the sea floor a Greenland shark that’s maybe 22 feet long and weighs 1,500 pounds? A shark that’s holding on to an 1,100-foot line attached to 20 feet of chain?

The Greenland shark can be used for more than just making sandpaper and nitroglycerin. Its flesh is poisonous, smells like urine, and can serve as a potent drug. The Inuit used to feed the meat to their dogs, if nothing else was available. But the dogs would get extremely intoxicated and might even end up paralyzed for days. During World War I, there was a shortage of food in many places in the north, and people couldn’t be choosy.

There was more than enough meat from Greenland sharks. But if people ate the meat when it was fresh, or neglected to treat it in the proper way, they could get “shark drunk,” because the flesh contains the nerve gas trimethylamine oxide.

The resultant inebriated state is supposedly similar to taking in an extreme amount of alcohol or hallucinogenic drugs. Shark drunk people speak incoherently, see visions, stagger, and act very crazy. When they finally fall asleep, it’s nearly impossible to wake them up. To avoid these side effects, you need to cut the main artery of a Greenland shark immediately, so that the blood drains out. Then the meat can be dried or boiled in water, which has to be changed several times. In Iceland, the shark (called hákarl) is considered a delicacy, but there everyone is careful to prepare the meat properly. To make the poisons disappear requires repeated boiling, drying, or even burying the meat until it ferments.

It should be no surprise that people living in northern Norway developed a healthy skepticism when it comes to the meat of the Greenland shark. The reason they even bothered to catch it was because the liver is extremely rich in oil. In the 1950s, Norway was the leader in commercial fishing for the Greenland shark, but by the early 1960s, demand was already fading. Only now is it making a small comeback.

If people ate the meat when it was fresh, or neglected to treat it in the proper way, they could get “shark drunk,” an inebriated state that is supposedly similar to taking in an extreme amount of alcohol or hallucinogenic drugs.

Our boat is gently bobbing in the sunshine in Vestfjorden. Yesterday the sea glittered and crackled with light. Today it has a steady, calm glow. The ocean has found its lowest resting pulse, as it does only after many days of good weather in the summertime. It’s also a neap tide, which means the difference between high and low tide is unusually small. The gravitational force of the moon and the sun pull the sea in opposite directions, canceling each other out to a certain extent, like when two people arm-wrestle and neither has an advantage.

Our only task is to wait and keep an eye on the floats. What’s going on down there on the sea floor, more than a thousand feet below us? Is the beast starting to sniff its way toward our stinking bait? The oily substances of putrefaction must be spreading like smoke from a flare, way down there in the water. What are we going to do if we actually manage to bring the shark up to the surface? I feel a certain fear mixed with anticipation at the thought.

An acquaintance who used to be a seaman on a trawler once told me what they would do if a Greenland shark got caught in the trawl net and ended up on deck. They would tie a line around the base of its tail, lift it up with the derrick, and swing the shark out along the side of the ship. Then they would cut off the tail so the shark fell into the sea with a big splash. The amputation was accomplished in a flash, since Greenland sharks, like all sharks, have no bones, only cartilage. The shark is very much alive when it lands in the water, but it quickly discovers that something is seriously wrong. We humans wouldn’t have much of a chance if someone chopped off our legs and arms, and threw us overboard in the open ocean. Without its tail fin, the shark is helpless. It can’t move forward or keep its balance in the water. After a short time it sinks to the bottom, and down there in the ice-cold dark, it’s most likely eaten alive by other Greenland sharks.

Watch VICE Meets Norwegian literary sensation Karl Ove Knausgaard:

Hugo tells me that something similar was done with basking sharks. It was common to turn the shark over and cut open the belly so the liver floated out. Then the shark would continue swimming without its liver, at least for a while.

They didn’t always cut off the tail of a Greenland shark. My friend the trawler seaman told me that sometimes they also painted the name of their boat on the side of the shark, as a greeting to the next trawler that happened to catch it. Whoever landed a shark like that in their net would paint the name of their own trawler on the other side of the fish and then set it free again. It probably would have been easier to send a postcard, but trawler crews have their own brand of humor.

“Look! Isn’t the float moving?” Hugo says. It looks like it’s popping up and down with the unnatural rhythm of a gigantic fishing bob. Something is definitely happening a few hundred yards away from where we’re sitting, in the middle of a shoal of mackerel. Hugo starts the motor, and in 60 seconds we’re at the site.

Hugo starts pulling up, meaning he hauls on the line, and there’s no doubt that something big has taken the bait. After a while I take over, and it goes even slower. Have you ever tried to haul up from the sea floor a Greenland shark that’s maybe 22 feet long and weighs 1,500 pounds? A shark that’s holding on to an 1,100-foot line attached to 20 feet of chain? The line digs into my fingers. It’s sheer agony. Stinging jellyfish have attached themselves to the line, and we’re not wearing gloves.

My arms are practically lifeless, and there’s no more than 150 feet left when all of a sudden it gets a lot easier. Anyone who has ever gone fishing knows the feeling of deep disappointment. In a hundredth of a second all your hopes are crushed. You go from being excited, determined, and focused to tumbling down the basement stairs. Even though the line had been cutting into my hands, it hurts more to feel the weight disappear. Hauling the line the rest of the way up seems like harder work, even though it weighs next to nothing. A few minutes later the hook attached to the chain is right under the boat. I lift it up so it dangles in front of us. When we dropped the baited hook in the water, the hip joint was covered with red flesh. Now it has been gnawed clean. Dozens of tiny orange parasites are scratching at the bone. They look like lice or little insects. They must be what live in the folds on the belly of a Greenland shark.

Down there, underneath our pontoons, our monster is swimming, waiting to be fed.

We can clearly see the sawlike marks left by the shark’s teeth on the bone and fat. The hook is stuck through a tendon in the joint so it lies right next to the bone. I had assumed the shark would crush the whole thing if it took the bait. But it didn’t. And that’s why the shark wasn’t hooked more firmly. That’s why it was able to pull free or simply let go. That’s why we’re sitting here, not saying a word. I tell Hugo about my mistake, and he just gives me a pensive little nod without a hint of blame.

After the initial disappointment has subsided, we decide not to consider the episode a defeat. Instead, we will view it as a sign that we’re doing things right. Not many people have been on the verge of catching a Greenland shark on their very first try. All we can do is rebait the hook and toss it back into the water.

Down there, underneath our pontoons, our monster is swimming, waiting to be fed. Several hundred yards away, toward shore, a boat is anchored. It’s filled with happy youths enjoying the glorious weather. The girls jump into the water, which is cold, but it’s never going to be warmer than it is right now. If they knew what was staring up at them from the deep as they splashed around, they would rush back on board. One of the girls is wearing an orange swimsuit and probably doesn’t know that the colors yellow and orange seem to provoke sharks to attack. Australian divers and surfers never wear gear in those colors.

We get no more bites that day. Or the next. On the third day we let the baited line stay out there all night. The following morning the whole thing is gone, as if sunk into the sea. Both floats are probably far out in the ocean, dragged off by some invisible force, either by the current or by a Greenland shark. It would be pointless to go looking for the floats. Even if we had all the time in the world and an unlimited supply of gasoline, the chance of finding them would be close to zero.

Three days later we’re on our way back across Vestfjorden. We’ve written off the floats and chain, along with the fishing line. But out in the middle of Vestfjorden, in poor visibility and high seas, we practically run right into them. The whole length of line and chain is there. Only the hook and shackle, the U-shaped steel clamp fastening the hook to the chain, is missing. That’s incredible. It shouldn’t be possible for a clamp, firmly fastened with a pair of pliers, to come loose. And it would take tremendous force to snap it in two. Yet one of these two things must have happened. At least that’s what we tell ourselves. But the truth is, it was amateurish for us to leave the baited line out here overnight. Local fishermen confirm this. The current is so strong that it will take everything, if given enough time.

Our boat carves a white V across Vestfjorden. Out in the ocean a small rainbow forms a portal. It’s tempting to set course toward it, just to drive through. But we’re not hunting rainbows.

The mirage line, where the sky meets the sea, is suddenly obscured, creating optical illusions. Several small islands out there seem to be much closer, floating above the glittering sea. The sun is burning the edges of magnesium-white clouds far to the west. It has rained, and we can see individually delineated local showers pouring down way off in the distance. The sun isn’t visible to us, but it casts its light around and in between the rain, in some places looking like gigantic spotlights slowly sweeping across the surface of the water. Where we are, the world seems cleansed and filled with mirrors. The colors are oyster shell and slate.

Translated from the Norwegian by Tiina Nunnally.

From SHARK DRUNK: THE ART OF CATCHING A LARGE SHARK FROM A TINY RUBBER DINGHY IN A BIG OCEAN by Morten Strøksnes. Published by arrangement with Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2017 by Morten Strøksnes.

More

From VICE

-

Photo: Gandee Vasan / Getty Images -

Photo: duncan1890 / Getty Images -

Photo: Jorge Garc'a /VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images -

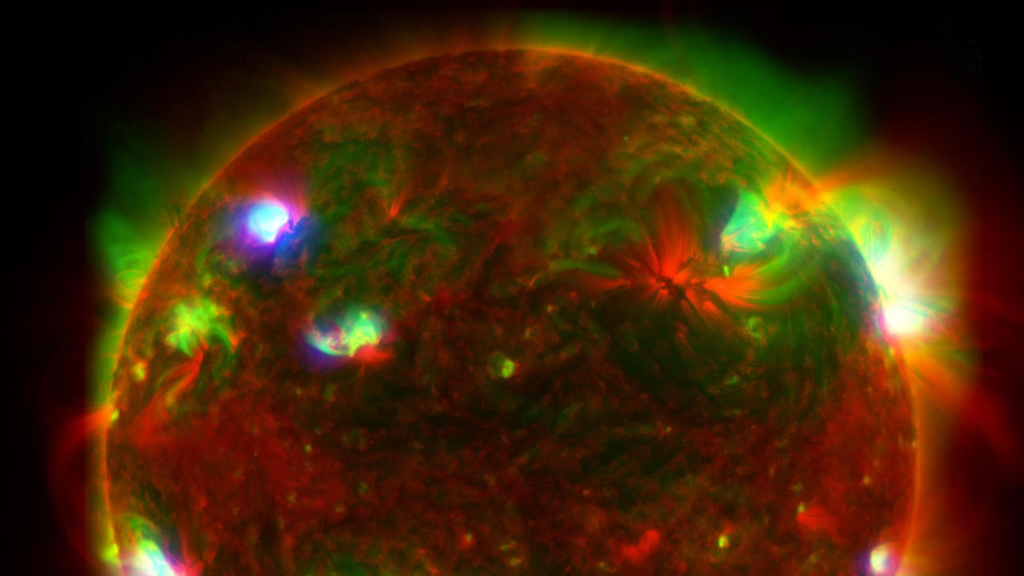

Three-Telescope View of the Sun. Photo: NASA