From Michael Jackson to Whitney Houston, Bruce Springsteen to Queen, few have ever captured legendary musicians quite like photographer and photojournalist Neal Preston. Over the course of his 48-year career, the New York–born, self-taught shutterbug witnessed the rise of rock ‘n’ roll and the global culture shifts that came with it. He’s shot books for Led Zeppelin as their only tour photographer, calendars for Elvira, and was tapped by Bob Geldof himself to photograph his 1985 “Live Aid” spectacular—and he did it all without ever taking a single class in photography.

As a freelance photographer and all-around creative here in New York City, Preston’s work inspires me every day. His level of mastery and versatility illuminates what you can accomplish through passion and dedication to your craft. When I heard he was releasing a new book, Neal Preston: Exhilarated and Exhausted, with a foreword by Cameron Crowe, I leapt at the chance to interview him. Preston was generous enough to offer insights into his craft and speak on a variety of topics including his legacy, the fate of the music industry, and the mindset that took him from high school hobbyist to living legend.

Videos by VICE

VICE: For the uninitiated, who are you, and what do you do?

Neal Preston: I’m a guy who believes in good fortune, and I fell into a job that I never intended to make a career out of. I didn’t go to college because I was in the middle of starting a career. So, I’m a guy who discovered rock ‘n’ roll music the day the Beatles were on Ed Sullivan, and also had been given a camera around 11. Both those things were my hobbies, and those two things morphed into my super hobby.

When you got your first camera, did you know anything about film?

I was given a camera by my first of three brothers-in-law. It was an Ansco Speedex 4.5. There was this lens with all these numbers on it, and there was also another dial, which was the shutter speed—I had no idea what that meant. Then I realized there was this thing that, if I cocked the shutter, it would go like this. So I cocked the shutter, took the picture, and now I was at least able to take a photograph. But that’s all I knew about photography, other than what everyone else knew: Take a camera, make sure the sun is over the shoulder…

My dad was a Broadway stage manager for all these big musicals. He was considered a real important guy, you know, golden age of musical theater. He worked on My Fair Lady, Camelot, Fiddler on the Roof, these big, big shows, and my favorite thing to do was to go visit him for a Saturday matinee. This was when I was old enough to get on the subway by myself, and I snuck a photo once of Harry Goz. It’s the first performance photo I ever took and made a print of. My dad gave it to Harry, and I guess Harry had been a photography buff because he had a series of books about photography. He gave them to my mom and dad to give to me, and I probably read them all within an hour. Other than that, I figured it out on my own. To this day, I’ve never had a class.

Were there any photographers who inspired you?

I didn’t know a lot of their names, but now that I’ve been in the business a day or two, I know who they were: Philippe Halsman, Allan Grant, whose widow is a good friend of mine… These were the guys who could shoot anything. I didn’t know about editors or editorial departments, so that’s what I was drawn to. My favorite fashion photographers back then were [Richard] Avedon [and] Norman Parkinson, who I realized later in life was the genius of all geniuses. I knew about the [Henri] Cartier-Bressons and Ansel Adamses, but they didn’t really appeal to me. I’m more aware of the guys who shot music and founded music photography.

Do you feel like having versatility is important as a photographer?

As a photojournalist, absolutely. Generally, photographers tend towards one area—advertising, fashion, editorial, which comprises photojournalism, corporate, all the different slices of that pie. For me, even though I gravitated towards music, I knew I could shoot a bunch of different things and different subjects and styles. Even if that style wasn’t my style. Case in point: for the movie ‘61 that Billy Crystal directed, about the home run race Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris had in 1961, I spent two days recreating baseball cards with these two actors in place of Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris. I can look at picture and tell you exactly how it was lit—I mean, as best as possible, using the equipment that I knew existed—then or now. So I can recreate anything. Somehow, I became known in the business as someone who can do that really well.

What’s one of your most memorable moments on tour?

It’s not moments as much as vignettes. Being on the Great wall of China with Wham! and George Michael. Going to Russia with Billy Joel for two weeks. I grew up in the heat of the Cold War and the Cuban Missile Crisis, and going to Russia was as surreal as going to Uranus or Pluto. Also, South Africa with Whitney Houston. Going through Checkpoint Charlie in the Berlin Wall with Bryan Adams. I’ve shot six Olympic games, so Torino, Italy, and Yugoslavia… those types of things.

But if I had to pick one single memorable moment, you can’t discount Sly Stone smoking crack in my car while I’m riding down the freeway. Sly Stone pulling out a little anvil case, dressed in Army fatigues. It’s 1979—and I’ll the whole story of the shoot another time, it’s fantastic—he’s opening up this case and pulling out a fucking butane torch, smoking a pipe that still I can’t see, and now it’s a Cheech and Chong movie with smoke billowing out. That was a single memorable moment. You can’t top that.

What do you do on off-days?

Well, off-days are golden because you rarely have them. What do I do? Assuming it’s a real off-day, where no editing is involved—don’t forget [I shoot] analog—a true off-day, besides trying to get a modicum of sleep, would be comprised of partying. Doing the stuff people think happens all the time on rock tours, which doesn’t. It’s about catching my breath and taking care of my responsibilities, while also trying to get some sleep. You don’t get a lot of sleep on the road—I don’t care if you’re on the road with Captain and Tennille.

In the trailer for your new book you say, “I’m not the story. What I do is the story.”

I truly believe that. We all know photographers who say, “It’s about me.” I’m not going to name names, but again, it goes back to how I perceive how I do my job. Everyone has an ego to satisfy, mine is less about, “Do you know who I am?” as opposed to, “Haven’t you seen that picture?” And that’s the story, which is why I wrote this book. The way I went about the job, about the potholes, the stresses, the deadlines, the constant travel, the little bit of personality management, all those things the people don’t think when they see that picture of Jimmy Page drinking Jack Daniel’s, those are the interesting things. There are tons of books like, “Here is a photo of Bruce Springsteen and we had a cheeseburger after the shoot and he is a great guy.” That’s been done a million times—I have a stack of books like that. That is not this book.

What’s your mindset when shooting shows?

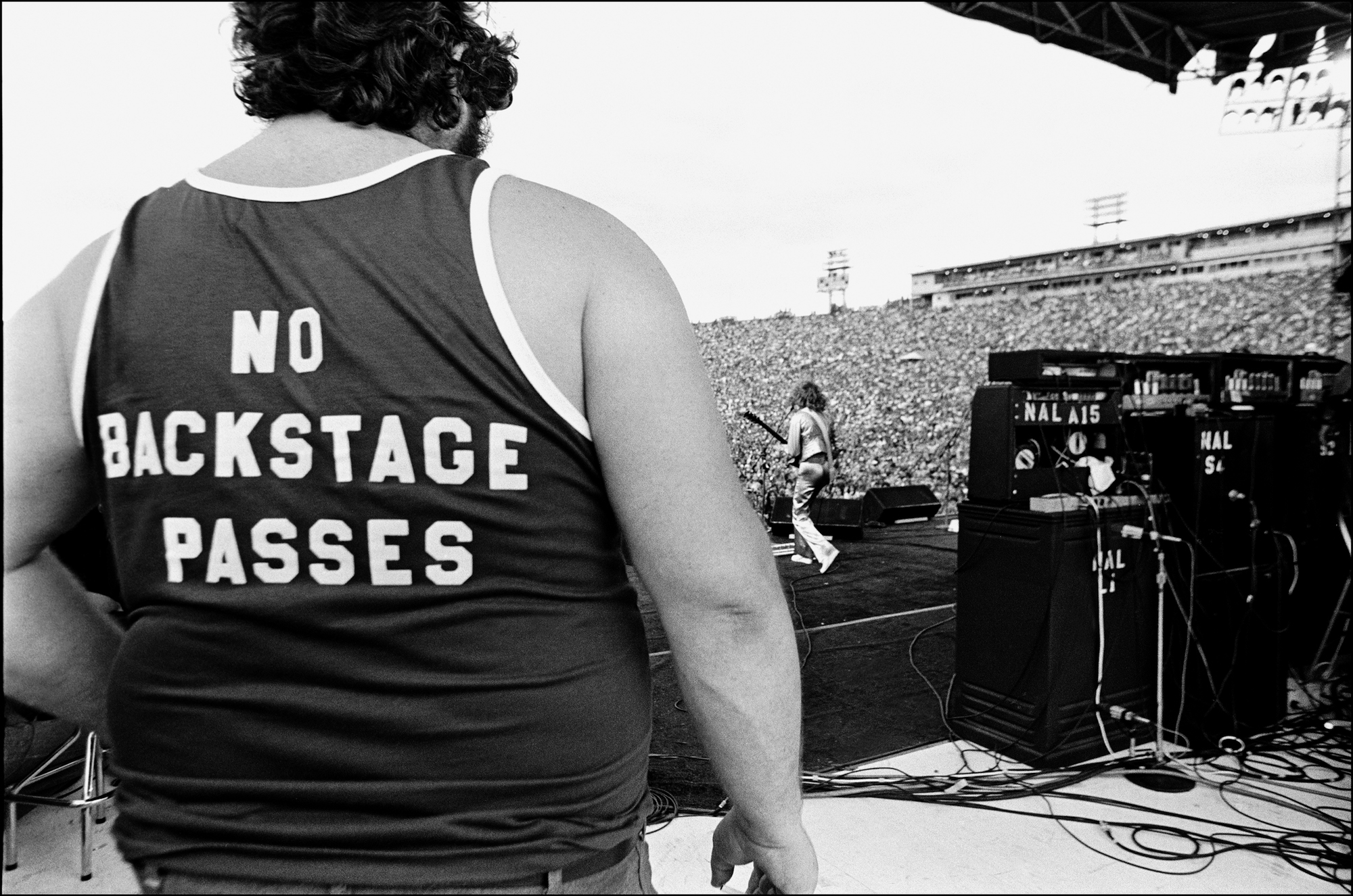

Well, I’m there to do a job. The minute you walk on stage at any rock and roll show, you are no longer in the United States of America. I don’t care if the show is in Topeka, Kansas, Manhattan, LA, wherever. You are now in the roadies’ nation state. As such, they are in charge even though the band is on stage, and there’s protocol that you have to be very aware of. You learn by common sense, keeping your eyes and ears open—and your mouth shut. Don’t step on anything, don’t touch anything, don’t breathe on any instruments, that’s the obvious stuff. Make sure your pass is visible at all times, because you are being tracked by 12 pairs of eyes, those roadies. And, most importantly, don’t fuck up. The minute you do, you’re gonna be shot down like an enemy aircraft straying into Russian airspace. You do not want to screw up the roadies’ job, because they are gonna get yelled at. If I trip on a cable and it gets pulled or unplugged, which, thank God I’ve never done—I came very close—I’m done! It’s their domain.

And, as I like to say during load out, be very, very careful. It’s not worth being impaled by a forklift because you’re trying to impress some chick from Memphis who you will never see again. Get out of the way!

What is something you would want a young photographer to take away from your book?

Well, my book is not a “how to.” It’s more of a “how did,” or, “how do I?” So much has changed in the business and the world since I started. I grew up before the internet, before cellphones, before declining photo budgets… A lot of kids ask me, “How do I bust into the business?” It’s good news/bad news. The good news is there are a lot more outlets for people to look at your work, given the internet. The bad news is, there is very little money, which I find very insulting. The best advice that I give to up-and-coming photographers is: latch onto one band you love. Ride that pony. If they become successful, you are their guy. Then they will tell people, “These are the photos to use.” That’s how you will become known to people in the industry—the best way to establish yourself, generally speaking. You’re not going to get far by calling Rolling Stone and submitting 18 portfolios.

Something that stands out is the high contrast, deep blacks, and intensified highlights of your black-and-white photos. Would you call that that “your style?”

It’s a style I like. It’s called “high-key.” If anyone has a style, my style when shooting live is indigenous to me. I wouldn’t say that about anything else I do, but when it comes to that on-stage stuff, I know what I’m doing. I like inky blacks, which is a term Woody Allen used when filming Manhattan. I like clean backgrounds—the less crap in the background the better. Get rid of the microphone if you can. As far as the high-key stuff, there is a little more drama to it, and I’ve been doing that since I was a junior in high school. There, in the Bob Marley original frame, there is a background singer who ruined the frame. When I gave it to my silver gel guy, I said, “Burn that part in,” so it made the photo. I know a strong image, but I’ve told that to hardly anyone. I don’t like to pull stuff out unless it’s absolutely needed.

What was going on in that famous Freddie Mercury photo?

It was the beginning of the show. It was the first song. I realized it was the third frame I had gotten. That said, I’m in work mode. I’m not thinking, Oh, I have an iconic shot, I’m just shooting, and I see the film the next day. Any photographer who tells you, ten minutes after shooting, “I have an iconic photo,” doesn’t know what they are doing, and hasn’t shot an iconic photo—you need the benefit of time and insight into the past.

What’s the one thing you want to be remembered for?

I wanna be known as a professional. I learned a lot of that from Ken Regan, who owned the Camera 5 picture agency—very famous for photojournalists—just by watching and listening. He was a big brother to me, and a consummate professional. So, I want to be a consummate professional to deliver the goods. Your body of work at the end of your life speaks for itself. Treat people fairly and have it not be about me. My ego doesn’t need it. Get the photos and appreciate the masters who came before me.

Order a copy of Neal Preston: Exhilarated and Exhausted.

Follow Elijah Dominique on Instagram.

More

From VICE

-

Collage by VICE -

Screenshot: Bytten Studio -

Screenshot: Warner Bros. Games -

Collage by VICE