We call them “skywalkers” — the Mohawk ironworkers who work the high steel, shaping and moulding the New York City skyline.

Though not widely known, it’s a tradition and occupation that many Kanien’keháka (Mohawk) people have been engaged in for hundreds of years — since the 1920s, workers from Kahnawake, in Quebec, and Akwesasne, which straddles Ontario, Quebec and New York state, have been instrumental in building the tallest buildings and bridges in the American metropolis.

Videos by VICE

My own grandfather worked on the reconstruction of the Statue of Liberty in 1986, while many of my uncles are, or were, ironworkers in New York City, all Akwesasne men.

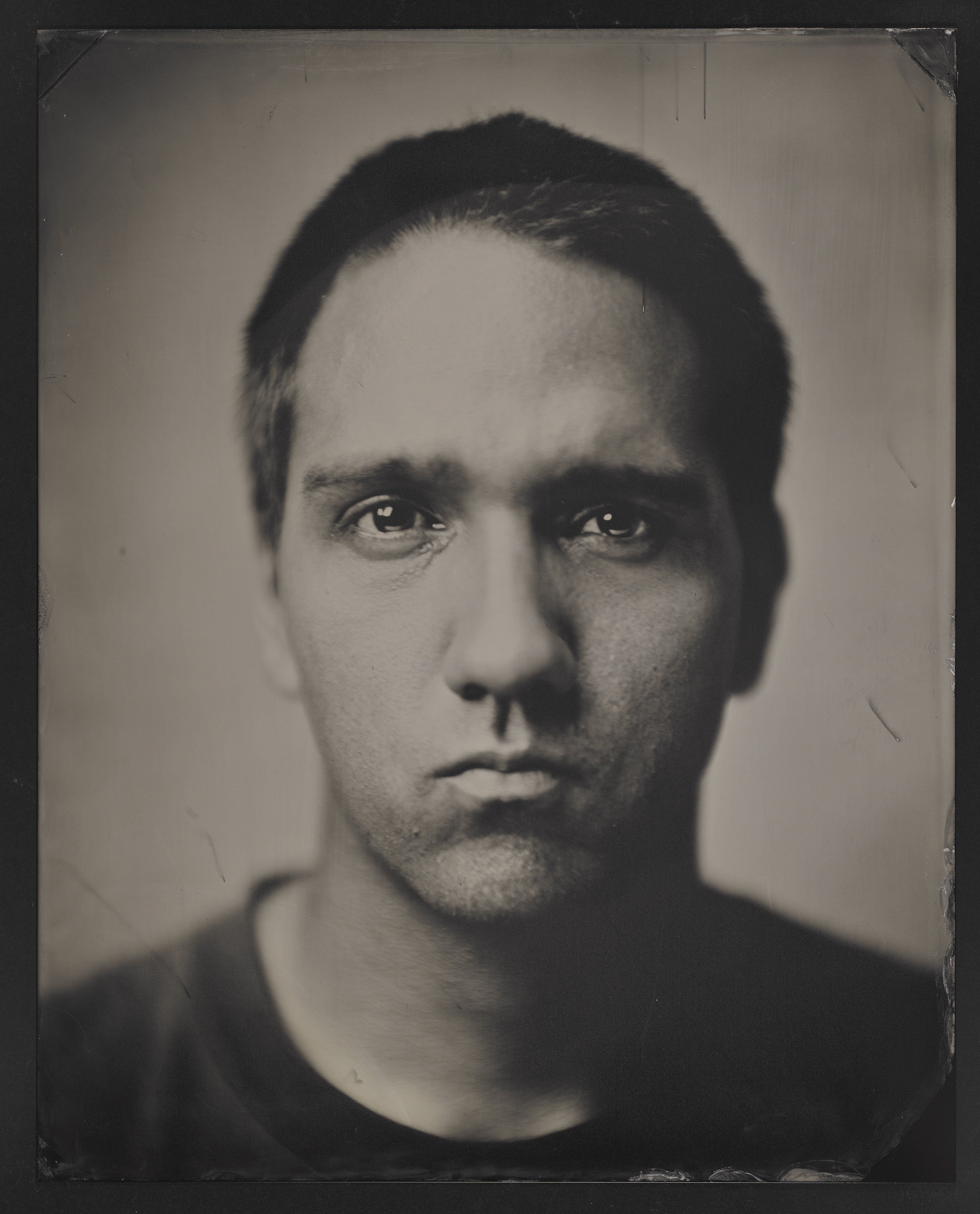

Now, the 9/11 Memorial Museum is aiming to put these skywalkers back in the spotlight with a new exhibition of portraits of Kahnawake ironworkers involved with either the rescue efforts after 9/11, or helping to construct One World Trade Center. The portraits are created by New York-based artist Melissa Cacciola. And the exhibition will include audio guides in the Akwesasne and Kahnawake Kanien’keháka dialects. It’s the first time audio guides at the museum are available in an Indigenous language, and comes amid a growing push to bring these languages to the forefront.

In 2012, Cacciola released a collection of tintype portraits — a 19th Century photographic process that uses a large format camera and period brass lenses — of 30 ironworkers from Kahnawake, entitled Skywalkers: A Portrait of Mohawk Ironworkers at the World Trade Center.

The 9/11 Memorial Museum exhibition, by the same name, will open on Nov. 16.

“We are extremely excited to use our platform to continue on the Mohawk language and share it with Native speakers, to allow visitors who may not have the opportunity to hear it otherwise to have exposure to it,” says Tara Prout, Memorial exhibition and registries manager. “We see how linked the Mohawk nation has been to Lower Manhattan and this iteration of the exhibition we tried really hard to contextualize Melissa’s work within the history of the story of 9/11 and the history of the World Trade Centre site.”

The Kanien’keháka recording for the Akwesasne dialect was translated by Margaret Peters, and narrated by Trina Stacey, a curriculum resource coordinator at the Kanien’keháka Onkwawén:na Raotitióhkwa Language and Cultural Center. Helen Norton translated the Kahnawake dialect recording, which was narrated by Stacey and Enhakanhoton Norton.

Prout says they wanted to show Cacciola’s work because the nature of the tintype setting – the subject must sit, unmoving for 10 seconds – and the goal for the museum itself were a match, as both venerate authenticity.

“There was a natural moment where we saw that this artist had captured the faces of the men, who in some iteration of the life cycle of this site, in the original construction of the World Trade Centre, Twin Towers, during the rescue recovery work that happened after the 9/11 attacks, and for this tremendous regrowth — we wanted to put these men on view where they’ve been able to contribute so much to our site and the history of New York City itself,” she says.

Dakota Stevens, the exhibition content coordinator, didn’t want to just display the portraits. He wanted to add something that brought the community in, in a way other museums don’t — which is to approach language speakers from those communities. Stevens and Prout made their way to the Kanien’keháka Onkwawén:na Raotitióhkwa Language and Cultural Center in Kahnawake and met Stacey and her elder Helen Norton. Stevens says they approached them about doing a translation for the audio guide as a way to fully express that the Kanien’keháka people are really the ones that never left. Stacey will be narrating what the ironwalkers wrote for the tintype artist.

“As we were walking around with Lindsay LeBorgne, a male narrator for the English voice in the audio guide, when he came down to record, he was pointing out buildings in the skyline that he’d help build,” recalls Stevens. “It’s not just a display of Mohawk portraits, but people who are living and breathing, and it’s important to introduce not only New Yorkers, but [people from] other countries across the world who come to our building, to a very important language.”

Stacey is deeply connected to this project, having been originally involved in Cacciola’s Skywalker exhibit in 2013, when she helped to translate some of the ironworker’s speech into a written form for the artist. Born and raised in Brooklyn, before moving to Kahnawake in 1973, she has her own ironworker family members.

She describes the process of translation as spending time to find the proper words in Kanien’keháka. For example, the elders she consulted with needed a description of what the World Trade Centre is, what they do there, before she could create a word for it. The elder would write it and Stacey would do the standardized orthography.

At this time in our call, Stacey stops us to talk about the correct words we’re using. She wants to ensure that we’re not using Mohawk — an Algonquin word for ‘man-eater’ — and instead use Kanien’keháka, meaning ‘people of the Flint.’ She gently reminds me that as a Kanien’keháka person myself, I should be using it, too. And she emphasizes one very important thing: “As far as I can remember, we were always taught that we were Onkwehonwe, first and foremost, which means a real authentic human being,” says Stacey.

“I think the 9/11 Memorial Museum is trying to bring authentic human beings together and remind ourselves that we’re all one on the earth,” says Stacey. “Yes, we’re Kanien’keháka people, and Kanien’keháka men helped to build this skyline of New York, but more importantly everyone involved in this project, we’re all real authentic human beings. I think it’s important to take this opportunity to teach that, because the world is going to pass through this museum and [we have] to remind the world who we are.”

Cover art of Norman. Tintypes by Melissa Cacciola. Reproduction photography by D. Primiano.

More

From VICE

-

Screenshot: YouTube/Assassin JorRaptor -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

(Photos via Liam Norris; baranozdemir / Getty Images)