If you go for a stroll on a small island in BC’s Gulf Islands you might come across a lonely plaque honouring 18 people.

The plaque, put up by Victoria’s mayor in 2000, reads “between 1891 to 1906 these men died on this island, victims to leprosy and prejudice.” For 15 years, this island served as Canada’s most notorious leprosarium—these days it’s only known as D’Arcy Island but a little over a hundred years ago it was known among the Chinese community in British Columbia as the “Island of Death.”

Videos by VICE

It is where the BC government would dump Chinese immigrants suffering from leprosy off to fend for themselves until they died.

“These were people who left their home to travel to somewhere very far away,” Erik Paulsson, a Vancouver filmmaker who made a documentary about the Island, told VICE. “They were just like everyone who came here, they were trying to make a little money and live happily ever after and then to have this experience, it’s terrifying.

“The idea of just being alone, dropped off in the middle of nowhere, it’s pretty traumatic. It’s almost a person’s worst nightmare really—just to be left to die.”

Paulsson spent over a year researching the island in the BC archives alongside author Chris Yorath. Paulsson and Yorath came out of a year of research with a book and documentary on the subject. “As I started doing research I uncovered this dark story, it wasn’t just about a leper colony,” Paulsson told VICE. “It was mostly just Chinese people sent there and because of the racism at the time they were really badly treated.”

“When one dies, [the lepers] had to drag them outside, dig a hole and bury them.”

Leprosy, which has been almost entirely eradicated in the Western world, was a terrible disease that caused disfigurement and nerve damage. It plagued humanity for millenniums and wasn’t cured until 1956.

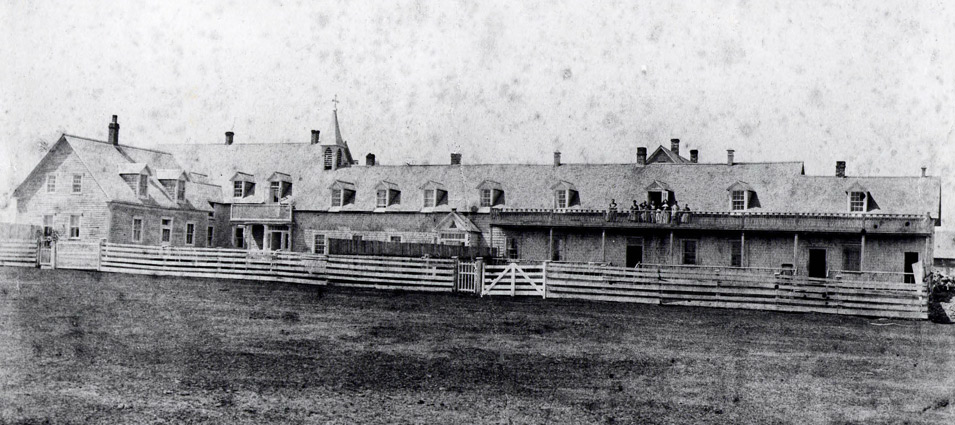

D’Arcy Island wasn’t the only leper colony in Canada. From 1844 to 1849 Sheldrake Island in New Brunswick was notorious for its poor conditions and after five years, the remaining people with leprosy were sent to Tracadie Island which had much better conditions. From 1849 almost all of the people with leprosy would be sent to Tracadie where they were cared for by the Religious Hospitallers of Saint Joseph until 1965.

However, Chinese people with leprosy, despite where they lived in Canada, were sent to D’Arcy—where they were left to fend for themselves and die alone. Whereas white people with leprosy would be sent to Tracadie.

“It was a terrible experience, they didn’t have anybody to care for them so they had to care for each other,” said Paulsson. “Imagine there is this pre-built shack that they drop you off at and they say ‘good luck’ and drop off food every three months. That’s it.”

D’Arcy Island was pretty much perfect for keeping those sent there at an arm’s length. The 180 hectare island was essentially a prison because of the strong current and low temperatures of the water made it pretty much inescapable—a few people tried but were never able to beat the current.

Henry Yu, an associate professor, historian and author at the University of British Columbia, researches historical racism in Canada and told VICE that D’Arcy Island is certainly a dark spot in Canadian history.

“I think it’s a rather tragic place for what it was used for and for the people who were sent to die there,” Yu told VICE. “There really is no other way to put it, it was officially called a leper colony but people were sent to that island to die. It’s not a pretty story.”

However, Yu explains, the most disquieting part of the D’Arcy Island tale isn’t necessarily the actual island—which he described as horrific—but the system that let it happen. It’s important to remember that at the same time D’Arcy Island was around, a leper colony for non-Asian people which featured a hospital and cook was being run in Tracadie.

“I think D’Arcy Island was one very powerful symbol but in some ways it’s misleading because it’s so terrible, but it’s also a symbol of the mundane nature of racism and white supremacy,” Yu told VICE. “It was a time where you could just send Chinese people with leprosy to die and no one blinks an eye. That’s perhaps more indicative to how normal racism was in that first half of Canada’s history.

“It was casual and it was cruel in how it would take someone who is Chinese with leprosy and someone white with leprosy and treat them so differently and yet it was so mundane. Something so horrific was normalized.”

In this era of Canada, Yu explains, white supremacy was pervasive throughout all of Canadian culture including all three governing bodies. This includes segregation, lack of voting rights, a head tax, and treating those who are non-white as a lesser human a la D’Arcy Island. It wasn’t until the late 40s that Canada and British Columbia “began to quietly dismantle white supremacy and then acted like it never existed”—put simply, Canada has worked to exclude this unsavory and shameful past from our national narrative.

“A lot of people talk about ‘well, why does it seem like no one ever talks about racism in Canada?’ Well, that’s because it was deliberately hidden and erased.”

According to Paulsson’s research, when the Chinese community learned that some among them had leprosy—the most feared disease of the day—they hid them from the government in a shack behind a store in Victoria’s Chinatown. When authorities found the men in 1891 they were taken into custody and the municipal council of Victoria requested use of the island from the government and set about making the colony. Within weeks of being found the colony was complete and the men were sent to D’Arcy. At the start of their journey to D’Arcy, one of the men, obviously dreading his fate, jumped off the steamer as it left and tried to cut his own throat with a knife. In the future, two men would kill themselves instead of going to the island.

Those who survived would be able to see steamers pass by and knew no help was going to come. Few people outside of health officers ever came to see them. One health officer described the situation as “truly deplorable” with only some of the people actually able to work and the rest being too debilitated by the disease. At one point a journalist named C.H. Gibbons traveled with the health minister and was swarmed by the inhabitants of D’Arcy Island who begged for information of the outside world.

“Every three months a small harbour steamer bears the municipal health officer and the stores that will keep the lepers alive,” Gibbons’ article reads. “These are the only breaks in the hopeless monotony of the lepers living death. The buildings are divided into little cell-like cabins, one for each leper. There he sleeps, reads, does whatever he can to kill the time that separates him from death.

“… As the days go by they waste away, growing constantly weaker and weaker, until some intercurrent disease releases them from their suffering and another rude grave is made in the woods and there is one less in the cabin.”

Conditions lasted like this for fifteen years. Once on the Island of Death, you were there until the end and year in, year out your only company would be other people suffering from the disease who would be dropped off to die—and these people with rotting bodies would be the closest thing to a nurse or doctor you would have. After fifteen years, the federal government took the island over began to give money to the BC government to improve conditions on the island and, a year after offering funding, the Leprosy Act which gave it full control. With the federal government running D’Arcy Island things slowly started improving. In 1924, the colony was shut down for good and the inhabitants were moved to a better facility on Betinick island which would be open until 1957.

On the island, the government burned the buildings and the remains of the colony to the ground. Over time the bodies D’Arcy Island claimed would be forgotten and it would eventually become a key spot in bootlegging Canadian booze down to the United States during prohibition.

“I’m being treated as a criminal though I’ve committed no crime. I’m being sent to an island prison from where no one has ever returned,” reads a letter written by a man Lim Sam shortly before he was sent to the island. “I have no idea what awaits me.”

“I don’t think I’ve been so afraid.”

Lim Sam never made it off the island.

Follow Mack Lamoureux on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

-

Eva Pascoe, founder of Cyberia, poses at the cyber cafe in London. All photos courtesy of Eva Pascoe, Ali Knapp, and Roger Green. -

Image: Andriy Onufriyenko -

Photo: Francesco Prandoni/Getty Images