Memory loss has been on my mind as long as I can remember. My grandmother died of Alzheimer’s in her 70s when I was in third grade. She spent her final days in a nursing home staring for miles down corridors, recognizing not even my mom when we visited her. A few years ago, I moved to Seattle to be closer to my wife’s family. Ten years ago, her mother was diagnosed, in her early 50s, with early-onset Alzheimer’s. It’s a devastating disease, a pain carried equally by those who have it and by their families. Some experimental treatments work to slow the disease, but so far, nothing reverses it. And we don’t seem to be talking about it enough.

While making Breathers, a series of photographs of looming Pacific Northwest trees as metaphors for this fading, I was inspired to look at how other photographers approach the disease. The following artists use photography to understand, process, and cope with their experience of Alzheimer’s, as well as dementia and other forms of memory loss. Some face it with a direct, documentary-style approach, while others use still life, abstraction, and other devices as visual metaphors. Cheryle St. Onge, Stephen DiRado, Norma Cordova (a.k.a. Shesaidred), Kija Lucas, and Birthe Piontek respond to family members who presently have or have died from the illness. Other artists, including Maja Daniels, look at how society cares for those impacted, while William Miller faces his own diagnosis. It’s heartbreaking and revealing.

Videos by VICE

In my research for this feature, I came across dozens of moving projects that I did not have the space to write about. I encourage those working within this theme to consider applying for the Bob and Diane Fund Grant, which has been an incredible inspiration.

Stephen DiRado

“All my life I have documented my family and friends, starting at age 12 to the present—I am 61 years old,” said Stephen DiRado. “It is something I do to connect to the world around me.” Throughout DiRado’s life and career, photography has been a ritual for connecting with his family and his larger community in Worcester, Massachusetts. So it felt painfully natural to photograph his father, Gene, over the course of his 20 years living with Alzheimer’s (11 officially diagnosed), capturing his progression and their shifting relationship. For DiRado, it helped him, reluctantly, accept the reality of the cruel and complicated disease. His series, With Dad, which earned him the 2018 Bob And Diane Fund Grant, will be published later this year by Davis Publications.

In the 1990s, after spending more than 30 years as a dedicated husband and father of three, Gene began showing signs. He spent extended periods of time in the bathroom, and sat staring blankly at a television screen for hours. DiRado and other family members began finding notes he wrote reminding himself to complete simple, everyday tasks, scattered around the house. “It wasn’t until he had no explanation as to why it took him hours to drive the 20 minutes to my sister’s house or why he could no longer make change from a $20 bill,” DiRado told VICE, “that we entered into a state of crisis.”

In 1998, Gene had a stroke and shortly after was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. While DiRado had photographed his father throughout his life, he began making scheduled “photographic sessions” to have some form of control over Gene’s worsening condition. The photographs from this period capture his many stages from different angles. Some are simply framed, emotive portraits—images showing the connection between father and son. For example, one tightly cropped portrait contains little information beyond Gene’s face, lit softly with available light, a shallow focus softening everything but his gaze. He stares downward, half smiling, light hitting his eyes, sparkling them slightly as if he, despite the depth of his dementia, knows something secret and magical. Other photos made over these two decades, especially those taken in his later years when he was admitted to a care unit, give more context to his deterioration. Family members surround him, cling to him, extend their touch whether he remembers them or now.

Photo by Stephen DiRado Photo by Stephen DiRado

Photo by Stephen DiRado Photo by Stephen DiRado In 2003, when Gene was still living at home, DiRado made what might be one of his most painful photos. Curious about how he spent his time in the bathroom, he asked Gene if he could photograph him there. Gene agreed, walked up to the mirror, and began staring into it. When asked to hold still for the photo, he refused, pointed at the mirror and said, “That man is looking at the camera, so why can’t I?” For the first time, DiRado realized his father did not recognize his own reflection.

“To my dismay,” he writes, “over months and now years Gene progressively got worse, gradually became detached, confused and lethargic. Determined to stay connected I kept making documents. I called it my job in order to make time to be with him.” DiRado felt a responsibility to photograph his dad in every stage—not only for himself but to help others understand Alzheimer’s depths and horrors. Soon to be published in book form by Davis Publications, DiRado’s With Dad will not only honor his father, who passed away in 2009—eleven years after he was officially diagnosed—but will hopefully help those currently affected by the disease.

Cheryle St. Onge

“I stopped making pictures,” said Cheryle St. Onge. “I stopped reading as much. I would call friends and just cry. Many photo friends said: Make work, make pictures, it will help. The idea of pictures of my mother seemed unconscionable. I feared I would never want to see them once she was no longer alive.”

Five years ago, when St. Onge learned her mother, Carole, was diagnosed with vascular dementia, she hit a creative wall. But in April 2018, encouragement from photographer friends Mary Ellen Bartley and Joni Sternbach pushed her to photograph her. “I instantly turned to her and said, ‘Let’s make a picture. This one is for Joni. This one is for Mary Ellen.’”

Since then, St. Onge has been making collaborative portraits with her mother as she moves through the disease. She titled the series Calling the Birds Home, a reference to her mother’s life as a painter and avid bird carver. “She knew anything and everything about birds,” she said. While she took the first few photos with an iPhone for their ease of catching the moment, she prefers to use an 8×10 camera, shooting one sheet of film at a time, her process slow, meditative, and intimate. Looking at the screen of the camera’s ground glass is a way of creating distance from the experience, yet it’s also a way to get closer to and connect with her mother despite her fading memory.

Many of the images are ethereal and almost out-of-body. In one photo, her mother lays back on a bed of snow, basked in late afternoon sunlight attempting to make a snow angel. Despite her fate, she seems blissful and at peace. In another image, cloaked in similarly magical light, she hugs herself, eyes closed, transported somewhere else, somewhere better. Other images are comfortingly mundane: in one, scissors hang above her head top of the frame as St. Onge performs a haircut; in another, her mother, face in soft focus, blows out the candles on a birthday cake.

While some viewers might understandably question her mother’s ability to consent to being photographed, for St. Onge, it’s an act of love. It’s an exchange that helps maintain their bond. Most importantly, it’s a way of preserving her mom’s dignity with warmth and devotion. They are a means of keeping her mother alive and in the moment and joining her on her journey while holding onto her life.

Birthe Piontek

In 2011, while visiting her family in Germany, the Vancouver-based photographer Birthe Piontek noticed her mother displaying the first signs of dementia. She was familiar with these signs, having experienced her grandmother’s battle with Alzheimer’s 15 years prior, and began photographing her family home as a way of psychologically slowing down the disease. These photos were the beginning of a seven-year series—and now a book published by Gnomic Book—titled Abendlied, which served as a backdrop for several smaller projects about her mother and grandmother.

Images include a range of portraits and still lifes signaling something isn’t quite right. In one tightly cropped image, Piontek’s mother stares directly into the lens, a colorful towel wrapped around her head. At first glance, it feels like a simple emotional exchange between photographer and sitter. But strange details begin to emerge. Her arms are crossed from under her shirt—her hands coming up through the opening in its neck. The towel on her head seems incongruous to her other clothes and her stare, while direct, is disconnected. In another image, a woman sits in the corner of a room, her back to the wall wearing a sheepskin coat—backward, completely covering her face and body.

“I’m interested in the surreal and poetic power of objects,” Piontek said, “how they can become stand-ins for emotions and the expression of a psychological state.” This unfolds in her arrangement and rearrangement of objects, the swapping of family member’s belongings across photographs so things and people lose their original function and identity. Even the most straightforward, or “documentary” images, are full of uncomfortable metaphors for the mind’s unraveling. “In this way,” Piontek added, “the sculptural qualities of an object are drawn out and they are transformed. Cups are not cups anymore—they’ve become a sculpture that stands for something else.”

In another series, Her Story, Piontek deconstructed old photos of her mother and grandmother to reflect the contortion and fading of memory. She cut into them, added layers, removed parts, and incorporated other materials like paint to create sculptures that she then re-photographed. The final images are distortions that might suggest the inability to remember someone as they once were.

While making these photographs hasn’t provided any specific resolve to Birthe’s experience with her family’s intergenerational illness, it’s helped her process the feeling of being helpless. “Taking pictures,” she said, “became a way to cope and to feel a purpose by turning this whole disease into something more useful than just helplessly watching a person disappear.”

Maja Daniels

Passionate, and concerned about the lack of visual representation of eldercare, Maja Daniels spent three years photographing inside a closed geriatric ward in France, home to Alzheimer’s patients. As she began working on the series, which she titled Into Oblivion, the Swedish photographer observed that, with the increase in diagnosis, limited resources were available to provide proper care. Her mission, with the help of the ward’s director, was to help improve the livelihood of those suffering from the disease and bring their experience to a larger audience. “I want to motivate people to think about current care policies and the effects they can have on somebody’s life,” she said.

Into Oblivion captures Alzheimer’s patients within the confines of an eldercare system. While Daniels believes that these institutions are important, not only to the lives of patients but also to enable their families to continue living fulfilling lives, she questions how sociological neglect of the elderly is reducing access to specialized care. Unlike Birthe Piontek or Cheryle St. Onge, Daniels’s pictures lack the warmth of a loving, devoted family member, which makes their fate uniquely heart wrenching.

Still lifes of bland hospital food—a nondescript bowl of tomato soup, a pitcher of what you’d imagine being lukewarm water—mingle with peeling wallpaper and impotently cast religious iconography. Patients stare off or struggle with the simplest of tasks. In one image, a man standing beside a hospital bed looks at his raincoat sleeve like it’s a foreign language or universe, unsure where he is or what he’s doing. In another, a patient faces a wall, her back to the camera. She’s transfixed, staring through it like a Magic Eye poster, hypnotized, between universes.

Daniels often felt conflicted about her role as a photographer. “I wanted to portray each resident and the situation they found themselves in a dignified way,” she said. “I felt uncomfortable at times, and I did sometimes question my presence.” During these periods, she put down her camera and volunteered in the ward, helping where she could. “By being there, I was able to attach them to the present, and this felt meaningful.”

She showed the pictures to staff and residents’ family members, giving them new insights into their patients’ experiences. The most impactful images were of patients standing at the locked doors that separate the ward from other areas of the hospital. Photographed from the same distance and perspective each time, they seem to approach the door as a gateway to the outside world, to their past, to the unknown. “We have no way of knowing/seeing how certain institutions function and that makes it very easy to turn a blind eye to certain things as long as we are not confronted with them,” said Daniels.

While the series encouraged some changes in the hospital environment, its largest impact has been on those have a personal relationship to the disease. “I still receive messages from people— care personnel, academics, related family-members to Alzheimer’s residents who recognize something in the images,” she said. “That is more than I ever could have hoped for.”

Kija Lucas

Sundowner’s syndrome, a condition associated with Alzheimer’s, causes individuals to think they are away from home and desperately need to get back. They may begin packing suitcases, collecting belongings, or repeatedly say they “want to go home.” This stage in photographer Kija Lucas’s grandmother’s disease inspired her series Collections from Sundown.

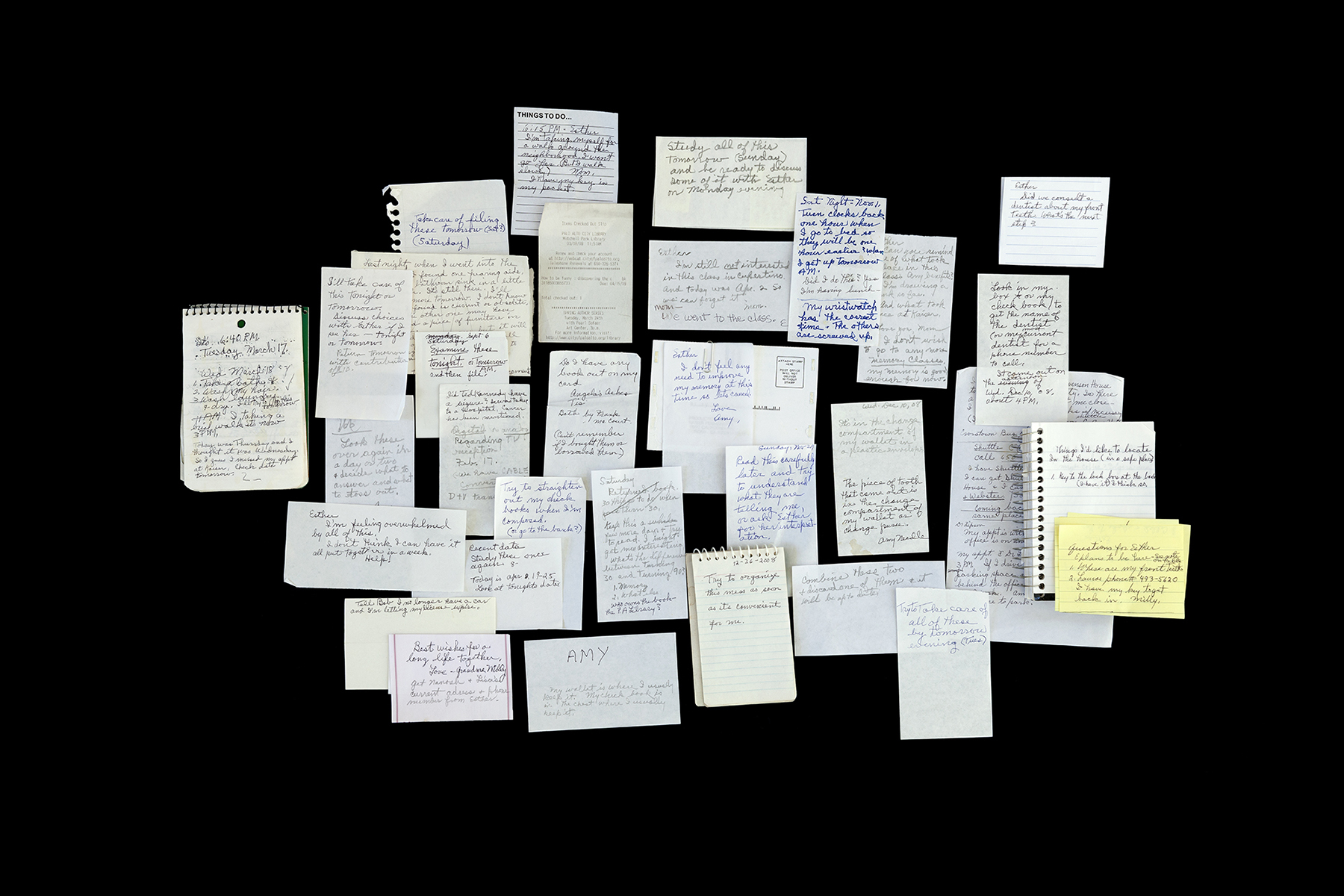

Shortly after her grandmother was diagnosed, Lucas began photographing objects her grandmother had packed for her imaginary trip. “I asked my mother, who was her main caregiver, to text me photos of what my grandmother packed so I would know what the items were and when they were packed,” Lucas said. “Then I would make still lives of them when I visited. I would also sometimes find her suitcase already packed.” As Lucas continued these visits, early in her grandmother’s illness, she gravitated toward handwritten notes that her grandmother wrote and left on the kitchen table. “I began collecting the notes…not knowing if or how I would use them.” A year later, when her grandmother needed more care, spent less time alone, and ultimately packed less, Lucas began arranging and photographing them.

Written on looseleaf paper, napkins, blank postcards, and even in the white space for a Paolo Alto Weekly postal service return address card, these graphic, almost typological still lifes give viewers a respectful and empathetic glimpse into her experience. They are discordant, often poetic. Shopping lists and other personal reminders appear in the same space as messages to family members. “Things I need to take/along when I leave./Check book/ Wallet. Purse.—/ Esther/ The flush in the—my/ toilet came apart again./Mom.” Reminders to bathe, locations of keys, recounting of conversations she had during the day. Lucas’s photographs and organization of her grandmother’s notes are a monument, memorial and complex illustration of the various stages of a mind slowing down.

While Lucas made the majority of these images when her grandmother was still alive, she did not once photograph her. She felt that it might violate her consent, but also that the notes could create an easier entry point for viewers without a direct connection to the story. “I felt like it would be easier for people to identify with the notes and objects, the repetition, the handwriting,” she said, “than it would be to see her physicality. I wanted there to be space for humor, and love, and all of the rest that goes with it, but I didn’t feel that for me it was the right thing to show her face.”

Despite their sense of dysphoria, humor occasionally punctuates the jumbling of words and ideas without sacrificing her grandmother’s humility. “Some of them made me laugh,” Lucas said. “I feel like that sounds dark, but I think my grandmother would have appreciated that she was making someone laugh.” For Lucas, making this work and finding jokes within the darkness helped dignify her grandmother’s humanity, keeping it safe from Alzheimer’s destructive grasp.

Norma Cordova

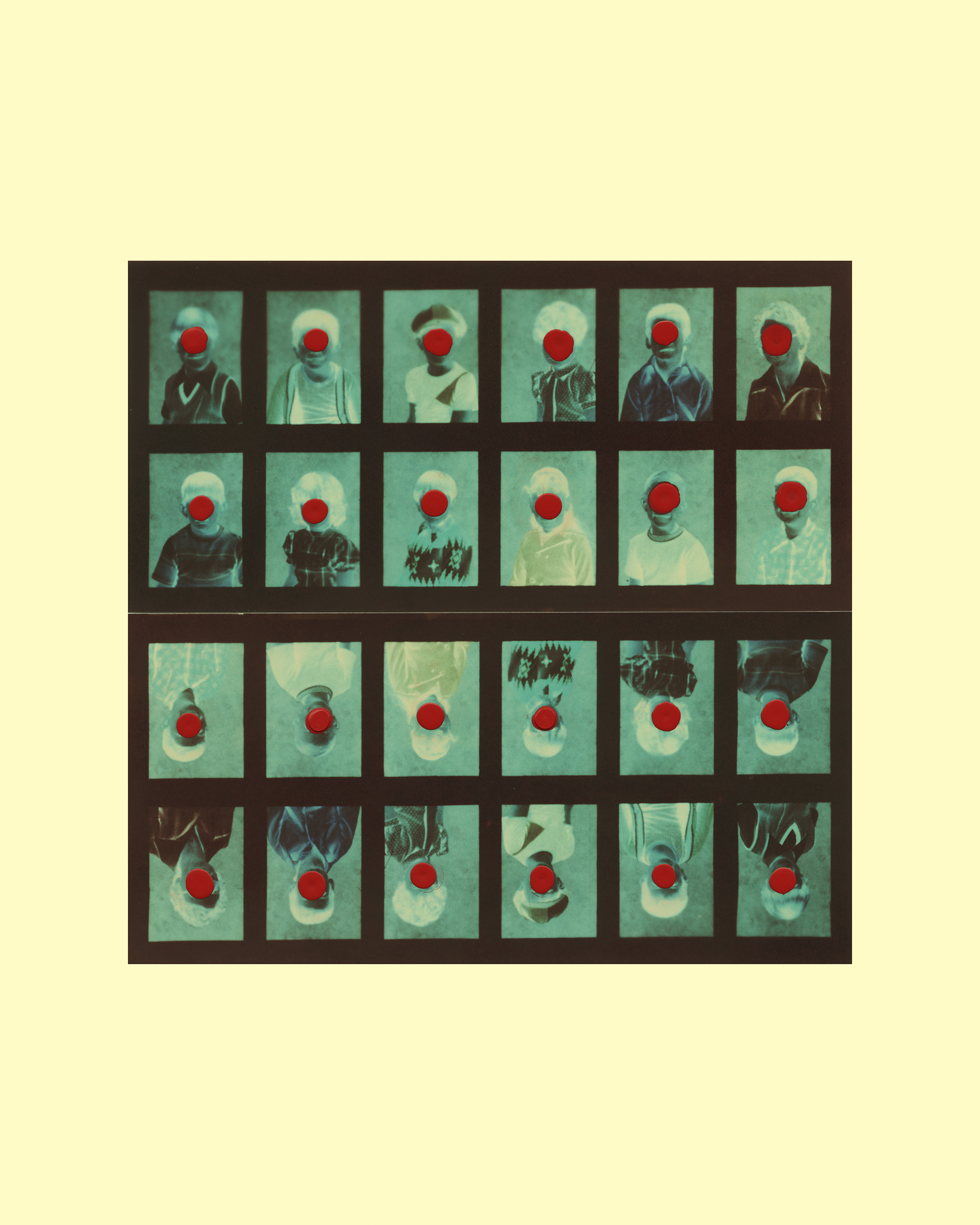

I met Norma Cordova, (a.k.a. Shesaidred) at Portland, Oregon’s Photolucida portfolio review in April. Rarely does looking at work in this context make me choke up, but the images and story behind her work was an immediate punch. In 1997, Cordova’s father was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimers. He struggled with it for a decade before it finally took his life. His ten years living with the disease changed Norma, her family dynamics, and what she describes as her own life trajectory. While she initially took some photographs to help her cope, it was years later, when she had some emotional distance, that she began her series, Fictitious Family. She began sorting through old family photos to look for clues to his disease and used them as the raw material for a remixed family photo album. “I needed to reacquaint myself with my childhood,” she says, “to see if I could find something that our family might have missed.”

Norma’s pictures are dark, dreamy, and cathartic. Often printed in the darkroom as reverse/negative images, they reflect the horror and confusion of living with the disease and her family’s reluctance to talk about how it was affecting them. “Their inability to have an open discussion about his condition,” said Cordova, “only made things worse.” Her process emphasizes that discomfort. Each image is full of visual anxiety.

Cordova often uses expired color photo paper to create blue and yellowing casts that respond to her nostalgia for the past and her search for, and ultimate inability to find a grain of truth or resolve. One image, for example, a photo of a man who we might imagine was her father, Norma prints using a technique that allows the text written on its back to shine through. She imbues it with a monochromatic blue cast creating an additional feeling of distance and disorientation. As viewers, we don’t know where to begin looking.

In other images, colored splotches appear on faces in family photos and class portraits from her childhood, obscuring their identities. Whether it’s paint, ink, or blood, it’s a symbol of not only the degeneration of the disease and the blurriness of memory but also her struggle to find answers and her own sense of clarity and to resolve the degradation of her family dynamic. Volleying between the portraits are images of what appear to be brain cells, a pacing reminder of the disease in case we forget.

“The implication,” she said, “is that everyone has their own personal untold story to share or unravel.”

William Miller

William Miller’s work stands apart from the others in this feature because it’s not about a family member. In 2016, Miller was diagnosed with Huntington’s disease, a condition that, while very different from Alzheimer’s, causes the progressive breakdown of nerve cells in the brain resulting in loss of motor control and balance, memory loss and aggressive and unpredictable behavior.

To help deal with his diagnosis, Miller began We Travel To, and Shall Be Lost in Always, a series of videos, sculpture, and photography responding to his experience living with the Huntington’s and his ongoing loss of short-term memory. Miller uses visual representations of expiring digital technology and “bit rot”—the glitchy decay and corruptibility of digit files—to symbolize what feels like a scrambling of his mind.

In an early video, an unfinished 3D scan of Miller’s face rotates 360 degrees while he narrates the experience of being diagnosed. A hereditary condition, Huntington’s is said to have a 50 percent chance of being passed down from a parent. It’s “the flip of a coin,” words Miller repeats throughout the video, and across several written statements about his work. As the rendering rotates, we learn of his initial confidence that he wouldn’t have the inheritance before the reality gradually unfolds. And as it continues, Miller’s voice stutters and glitches, as we hear his signs and struggles to remember and recount.

In another piece of the series, JPG Portraits Miller combines multiple studio self portraits, first saving the digital files individually at such a high compression that they lose mass amounts of visual information and become porous in their attempts to recreate it. He uses the Photoshop 3D module to make a depth map from the remaining blocky JPGs. It looks a little like how “futuristic” visual technology was imagined in the 1980s. Rough, patchy and pixelated—almost Lego-y in its botched struggle to fill in the holes.

Miller’s play with technological degradation is an upsetting reminder of the fragility of our minds and memories, and the importance of appreciating every day of life. Despite his painful fate, his approach to making art as a means of understanding his diagnosis, which he describes as an “existential threat,” initially gave him a newfound sharpness of perspective. It inspired him to give up drugs and alcohol, to get into a stable romantic relationship, to have a child and go to graduate school.

“Before my diagnosis, my life was absolutely not going this way,” he writes. “I may never have done any of these things without this illness which put the end of my life close enough for me to see without squinting.” Two years later, Miller says the feeling of urgency has subsided. “I don’t feel the same sort of urgency,” he adds. “In a way I’m sorry. I would like to keep some of that feeling of crisis.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Jon Feinstein on Instagram.