On November 5, 2018, NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft crossed into interstellar space, some six years after its twin, Voyager 1, made the same transition. There, it found something new and puzzling that its predecessor had missed.

For the past year, scientists have pored over data collected during the lead-up and aftermath of the probe’s passage from the major sphere of influence of the Sun into the void between stars, called the interstellar medium.

Videos by VICE

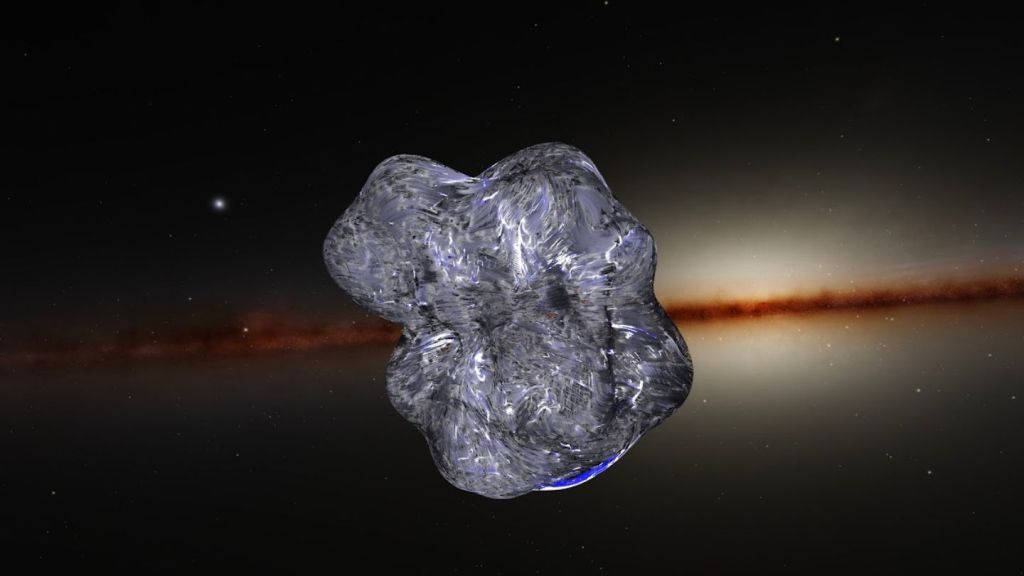

The boundary between these two realms, known as the heliopause, is a dynamic environment. This is where galactic cosmic rays, which are high-energy particles from alien stars and distant galaxies, slam into the bubble-like magnetic shield created by the Sun, which encompasses the solar system.

The Voyager probes are the only human-made objects that have ever traversed this tumultuous borderland between the Sun and the stars. While the twin probes sent back many similar observations, Voyager 2 encountered new phenomena while entering the interstellar medium, according to a packet of five new studies published on Monday in Nature Astronomy.

For instance, Voyager 2 discovered a previously unknown border just outside the heliopause, reports a team led by Edward Stone, a professor of physics at Caltech and project scientist on the Voyager program since its inception in the 1970s.

The researchers call this threshold a “cosmic ray boundary layer” because it signals where the probe experienced a shift in the gradient of cosmic rays from the great beyond and the lower-energy particles typical of the familiar environment around our Sun.

There’s evidence that Voyager 1 also encountered one of these cosmic ray boundary layers, but interestingly, it was located on the inside of the heliopause.

“There appear to be cosmic ray boundary layers on both sides of the heliopause, with the outer one only being evident at the position of Voyager 2,” Stone’s team said in the study. “This cosmic ray boundary layer on the outside of the heliopause was not evident at the place and time where Voyager 1 crossed it.”

It’s not clear why the probes ended up crossing through these layers on opposite sides of the heliopause. It could be related to the contrasting trajectories of the Voyagers, with Voyager 1 exiting the heliopause in the northern hemisphere and Voyager 2 leaving from the south.

The edge of interstellar space is also a rapidly changing environment, and the Sun’s activity had declined in the six years between the two transits, which surely influenced the conditions experienced by both probes.

Regardless, Voyager 1 recorded an influx of high-energy cosmic rays before it ever passed through the heliopause. “We had two episodes [on Voyager 1] where we were connected to the outside,” Stone said in a teleconference on Thursday. “In that case, we saw the leakage from outside in.”

Voyager 2 recorded the exact opposite phenomenon: an increase in low-energy particles from the heliosphere after it crossed the line into interstellar space.

“We can take another look at the data we have to try to understand what the process is by which the particles which are inside start leaking out,” Stone explained in the teleconference. “There appears to be a region just outside the heliopause where there’s still some connection back to the inside.”

This spilling of particles from both sides of the heliopause highlights what a bizarre environment lies at the edge of the Sun’s magnetic influence. Still, despite its apparent permeability, most cosmic rays never make it past the heliopause and into the solar system.

This has been a good deal for life on Earth because galactic cosmic radiation is damaging to biological beings. For this reason, a better understanding of the heliopause has implications for identifying potentially habitable star systems and exoplanets beyond our Sun.

The Voyagers are the first probes to send direct observations of this important boundary back to Earth, and to spend eternity beyond it. Let’s hope they are not the last.