The neat way to start this story would be to recount the moment I stepped out onto Edinburgh’s streets the day of Harry Potter: Wizards Unite’s release in the UK. Having ridden the train through the lush lowland greens of central Scotland, I walked up from the subterranean train station only to be confronted by the vertiginous medieval buildings of the Scottish capital.

It’s difficult to imagine how JK Rowling’s original series of Harry Potter books could have been written anywhere but Edinburgh, the city rich with history, tradition, and atmosphere that helped turn those stories into a reportedly $25 billion franchise.

Videos by VICE

But I think a more appropriate way to begin would be when I was riding my bicycle to catch the train. I stopped at a traffic light and just in front of me was a John Wick 3 billboard suspended in mid-air like a promotional apparition. Closer still was a Just Eat contractor biking to a drop-off, the company’s logo emblazoned on their delivery bag in bright red. I wish Harry Potter: Wizards unite transported me to a world of magic and mystery. But as I’ve played more of the game, it’s become harder to shake the feeling that, fundamentally, all it does is extend the brand into the everyday.

Like Niantic’s prior (and still widely played) augmented reality (AR) smash hit Pokémon GO, the game plays out in the mundane and real world of our everyday lives. Look down at your iOS or Android phone or tablet and you’ll see a wizard moving about a Google Maps-like interface, various icons designating locations and potential events. Encounter one of the game’s Foundables or Confoundables “stuck” in the real world—basically magical objects or memories displaced by chaotic magic or creatures—and you can free or dispel them by pointing your camera at it and casting a gesture-based spell.

Ironically, given the technologies involved, Niantic’s latest offering feels a damn sight cruder as a piece of brand marketing than the seemingly old fashioned billboards and uniforms. Where those are folded into the physical world—indeed, inseparable from it— Harry Potter: Wizards Unite feels strangely detached from the world we’re already experienced. It isn’t integrated into reality, but slathered on top of it. In spite of that lack of grace, the game does take the franchise into genuinely new territory. AR, at least for Time Warner (the franchise’s parent company), is an unexplored frontier ripe for commodification. And thanks to Niantic, Harry Potter is now literally everywhere (at least in the North American and European territories it’s been released in so far).

I started the game sat outside a cafe on Princes Street where I immediately ran into Hagrid trapped by a giant spider’s web. Having freed him, I walked a few hundred meters up to Calton Hill, climbing its steep slopes before arriving at a wide expanse of grassy, public space punctuated by grand, neoclassical monuments. There, I battled masked foes by tracing shapes on my phone’s touchscreen, and collected yet more Foundables (you will gather a lot of seemingly random stuff) while everyone else took photos of one another.

As I wound my way up towards Edinburgh Castle through the meticulously preserved “old town” things started to get weird. I saw a wizard screeching at the top of their voice as they delivered a guided tour of the city, and children posing with wands bellowing “patronum” as their parents took holiday photos. The only problem for Nianatic is that these aspiring wizards were taking part in real-life roleplay, not playing its game.

Which is to say Edinburgh is already bizarre enough without dipping into augmented reality. I visited Greyfriar’s Kirkyard, a cemetery next to the cafe where JK Rowling wrote some of the first books in the series. Not only did I find Thomas Riddell’s grave—widely assumed to be the inspiration behind Lord Voldemort AKA Tom Marvolo Riddle—but next to it were two goblin-like creatures fighting over a grandfather clock. Then, in the cafe itself, The Elephant Room, an action-figure sized Argus Filch appeared on my desk, chained to a lumpen metal ball. Inside the cafe’s lavatories, I found something different, thousands of scrawled messages—some silly, some heartfelt, some just kinda rude—which almost felt like an analogue AR, layers of time and reality built up over one another and smooshed together.

More ominously, the game casts you as a wizard for the State of Secrecy Task Force, an international task force established by the Ministry of Magic and the International Confederation of Wizards. It’s your job to clean up what the game calls the Calamity, the outbreak of magic into the muggle world. The Ministry of Magic, it’s important to remember, saw a tumultuous, troubling history in Rowling’s original fiction. Seemingly benign at the outset of Harry, Ron, and Hermione’s story, the organization evolved into a Voldemort-controlled enforcement agency of his police state, a situation it arrived at only through the willful ignorance of its Minister, Cornelius Fudge, during the build-up. In the depths of Voldemort’s control, the Ministry resembles the state apparatus of Vichy France during World War 2, the Nazi-backed government which controlled the southern half of the country. It’s this problematic, sometimes authoritarian institution which the game asks us to work for.

It felt like the game internalized not only the willful ignorance Fudge-era Ministry but also the exclusionary prejudices that laid the groundwork for Voldemort’s reign. As I aligned the symbols on my phone with the Confoundables which were materializing through it, there were points where a homeless person was included in the frame. Once you enter into the battle, Niantic’s game takes a screenshot which is then used as a backdrop. These types of encounters are bound to arise when you’re playing the game in a city the grip of a well documented homelessness crisis—but it felt jarring, uncomfortable, not to mention offensive, that the game transforms people and places into decorations for my personal playground. Folks without—and even those lucky enough to enjoy—the privilege of presumptive privacy, had no choice but to be subsumed within my game world. Anyone who didn’t fit into its defined limits of play was cast aside as invisible furniture.

Is it fair to criticize Niantic for not acknowledging this hyper-specific moment in the game itself? I don’t think so. Should Niantic aim to account for these types of moments in the game itself? No, because that would likely slip into its own queasy type of exploitation. But this particular experience struck me as an unavoidable outcome of Niantic’s fundamental notion that anywhere in the real world is a potential game environment.

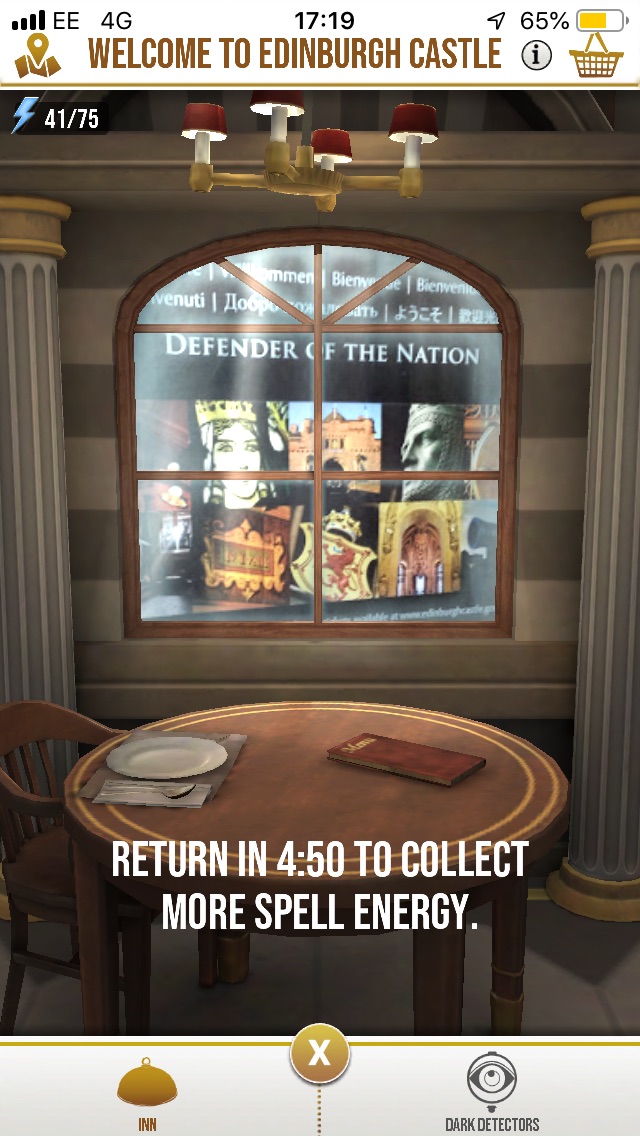

Elsewhere, the game does in fact acknowledge IRL phenomena through its naming of various inns and greenhouses which help you earn spellcasting power and ingredients. As I checked into these landmarks, I experienced a minor release of dopamine registering that the game knew my location—but as I visited more inns, the game’s passing glances to geographic specificity began to feel exploitative. Niantic has turned these places into nothing more than in-game props for its own commercial gain. Indeed, reports suggest that the game is on course to rake in $10 million during its first month.

I wound my way out of Edinburgh’s “old town”, along Canongate, before arriving at the sleek, modernist architecture of Holyrood, the Scottish Parliament Building, which is flanked by yet more wide open green spaces. Once I’d dispelled a giant and helped set free a magical rhino-like creature, I saw something else the game couldn’t possibly account for—a group of youth climate protesters waving their banners and chanting towards the politicians in the grand public building. I asked them what they thought Harry, Ron, and Hermione would have to say about climate change.

“I think they’d be outraged that young people aren’t being listened to in the same way that Cornelius Fudge didn’t listen to them when they told him Voldemort was back,” Lucy, 17, told me. “They’d probably be part of organizations like this, especially Luna who’s so passionate about magical creatures and Neville because his plants would probably be struggling.”

Anna, 14, continued, “They would definitely be out protesting. In the early days of setting up the climate strikes we felt a lot like Dumbledore’s Army—we were trying to work with the schools but the schools were working purposely against us. Harry, Ron, and Hermione were always very aware about what they needed to do but also to speak out for what they believed in. That was one of the main themes throughout the books.”

The subversive, perhaps even radical element of JK Rowling’s original fiction which Lucy and Anna identify with is conspicuously absent from Harry Potter: Wizards Unite. When you consider that Niantic used to be part of Google and that it’s CEO John Hanke played a major role in the development of Google Maps, well, perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that the studio prizes broad appeal and scalability (a revered quality within technology companies) over the political activism of the series’ founding characters.

But Harry Potter has never been as straightforward, nor egalitarian, as Rowling might like to present. The original books were noticeably white and heterosexual, marginalizing its ethnic-minority cast of Cho, Dean, Blaise, Lee, Angelica, Kingsley, as well as twins Parvati and Padma Patil, to the realm of supporting characters. None were part of what Rowling calls the “big seven” i.e. Harry, Ron, Hermione, Ginny, Neville, Luna, and Draco. In the most recent Fantastic Beasts film, Rowling attempted to respond to the increasingly fascist actions of populist governments across the US and Europe albeit channelling some distressingly piecemeal appeasement tactics through Dumbledore (as The Mary Sue pointed out). An alleged domestic abuser, Johnny Depp, was cast as the antagonist of that film, too. JK Rowling’s own increasingly harmful politics—the most recent development of which is her following of the TERF Magdalen Berns on Twitter—are also inseparable from a series rightly criticized for its monocultural view of the world.

Playing the game in Edinburgh itself also cast the franchise in a new light. The climate activists helped me understand there’s a resonant element to Harry Potter centered on the young people’s suspicion of authority and their commitment to challenging power. But those values have been bastardized by rampant commercialization over the two decades since the books were released. Edinburgh feels similar, a city which, in spite of its obvious beauty, is perpetually on the hustle. It is a space, ultimately, of commerce which Harry Potter: Wizard’s Unite feels depressingly in tune with.

It is yet another example of the already imperfect, messy franchise entangled with an even more complex reality. And like the head-in-the-sand-approach practised by the Ministry in the original books, iIt feels like Niantic is content ignoring these aspects of the Potterverse and our own world.

As I checked into inns, fought Confoundables, and returned Unfoundables, I was bombarded by an assault of numbers, colors and data loudly proclaiming that I was levelling up. Play was reduced to a series of stats merely designed to incentivize me into playing more.

The game borrows liberally from social media platforms, its user interface a barrage of tantalizing notifications, each one a miniature reward releasing yet more endorphins into my brain. The numbers, experience points and notifications are all purposefully folded into the free-to-play structure of the game which aims to keep players hooked for as long as possible, the rationale being that the longer we spend in it, the more likely we are to spend real world money in the game’s predictably named Diagon Alley. If you’re playing on an Apple device with Touch ID, payment is reduced to a single finger-print recognized button press, the barriers inhibiting capital almost magically invisible.

Such presentation feels totally in-keeping with the ruthless merchandising of the Harry Potter universe—indeed, just a logical extension of what came before it. And intentionally or not, Niantic has created an AR mirror to an already dissonant, problematic franchise and the real world it exists within. The overlapping realities have always been there except now we have an app for it.