Is the UK’s austerity program really such a terrible thing? Sure, in times of crisis people do tend to smash each other in the head more often, underestimate the value of their own lives, and end up cast adrift in a hellish world of drugs, mental illness, and homelessness. Then again—and sorry to pull rank here, but I’m from fucking Greece, so I know—austerity also helps strip the pointless bullshit from people’s lives. No more taxis. No more expensive hangover pizzas. No more white peacocks for your garden. No more diamond slippers… these things don’t seem quite so important when you’re preoccupied with figuring out where tonight’s dinner is going to come from.

Si Barber is a Norfolk-based photographer who, for the past six or so years, has been sensitive enough to the hilarity of life in credit crunched Britain to photograph it honestly. I don’t know if that means anything coming from a foreigner, but browsing through his The Big Society project I’m met with images of the Britain I dreamed of as a kid and came to love as an adult—the wonderfully fucked-up loner of Europe.

Videos by VICE

I spoke to Si about his work.

VICE: Hi, Si. So you’ve been working on your Big Society project for a while now, right?

I am always working on The Big Society. When I started it in 2007, I could just spend a couple of hundred dollars on diesel, accommodation, and food, and run off to Scotland for the weekend—it would all just be absorbed within my business, which is commission-based photography. Now that times have gotten a bit harder, I try to get as much out of a shoot as possible. I’ll go off and do two or three things at the same time.

Do you ever get involved in a project you absolutely hate?

I don’t hate any of them, but I do find the imagination of some of the people who commission work fairly limited. I also work quite a lot for broadsheet newspapers, and they have a limited view on what constitutes a good picture. They might ask for a bit of side-lighting, for example, which is a little bit old hat.

What I like about your pictures is their simplicity. It seems like you just point your camera at something interesting and take a picture that makes sense.

Is there a particular image that stands out to you?

The Flower Queens

I really like the photo of the Flower Queens. The Barbie memorial, too.

There’s a sort of underlying sadness in both those pictures. The Flower Queens one is particularly interesting because this year’s parade was the last parade ever. It takes place in Spalding, Lincolnshire, which is a very rural area and a center for the flower industry—if somebody buys you flowers from a gas station in England, they’re probably from Lincolnshire. Anyway, the parade used to be funded by the local council and the local businesses, but nobody has any money now. They’ve also had a lot of immigration coming in from Eastern Europe, so there’s a sort of tension. Not of the physical violence kind, but a cultural tension, which makes the place quite interesting.

What about the crucified Barbie?

That was up in Cumbria on a road called the A66, which is locally known as quite a dangerous one. There are loads of accidents but the saddest thing is that the councils clear away the memorials once they are set up. Officially, they’re regarded as a form of advertising, which I think is quite sad, really. Then again, they really look cheap. “Sorry you’re dead but this five-dollar trinket is all I can spend on you.” But that’s just my opinion, I wouldn’t want to degrade anyone’s memory. In any case, I find them interesting. They stay up there for a few days and then they disappear as if they’d never existed at all.

Road accident memorial, on the A66, Cumbria.

What’s your favorite photo?

I think it’s the one of the Claudia Schiffer poster that’s been covered up with a painted on hijab. I saw it in Oldham in Manchester, an area with a large Muslim population, and what I like most about it is the bus in the background. To me, this is a very traditional English symbol—I think it creates a certain tension in the picture, which I enjoy.

One thing I have noticed about your pictures is that a lot of them are devoted to army life. What’s that about?

I grew up as a military child. My dad was in the Royal Air Force and the thing that always strikes me about the military is that they have this sort of front where everything is orderly, but behind the scenes it’s a total disaster. For example, the rates of the divorce of people in the military are absolutely huge—it’s over 50 percent.

The body of Private James Grigg is conveyed into Stradbrook Church, Suffolk. The 21-year-old became the 257th member of the British forces to die in Afghanistan when he was killed by an explosion in Musa Qala.

A level of patriotism runs throughout your photos. To me, it seems bittersweet, as if they are saying, “England’s great, England’s funny, and England’s fucked up.”

You’re absolutely right. When times are tough you tend to see surges of patriotism. Like with Thatcher and the Falklands. My dad was involved in the war—I was 14 when that war kicked off. At the time nobody knew where the Falklands was, people thought it was near Scotland. After Thatcher won it back, it became this huge part of England and Englishness. Which is all completely manufactured, really.

Royal Wedding celebrations.

You mentioned you started working on The Big Society in 2007. What came first, the idea for the project or the photos of Britain in recession shock?

I was walking around Cambridge and I went down a street and there was a big line of people standing outside a Northern Rock branch. They were lining up to get their money out because the bank had gone bankrupt. It was the first bank to go bust in this country in 150 years. It struck me then that there was something afoot, because there wasn’t much in the papers about the crash at the time. I started taking a few photos here and there, and as the credit crunch came on, I started doing more. The difference was then that I didn’t have to go and find subjects, they tended to appear in my way more and more frequently.

Would you say a bad economy contributes to absurd behavior?

Absolutely. The ironic thing is that the best pictures happen in bad economies. I started the project in 2007 and I was going all over the country back then looking for subjects. But what I’m interested in is not the big picture—not the riots and stuff like that—what I care about are the smaller things. I want to photograph the roadside memorial, not the accident. When you look at the picture of the accident you get the shock of seeing somebody injured, whereas with the memorial you get a look at the pathetic nature of life. I don’t mean that life is pathetic, but putting together this memorial with a couple bits of wood can give you an idea of the fragility of life more than anything else.

See more of Si’s work here.

Follow Elektra on Twitter: @elektrakotsoni

More:

The Soul of UK Garage, As Photographed by Ewen Spencer

A hijab painted over a cosmetic advert featuring Claudia Schiffer, Salford, Manchester.

The Hen party.

Street auction, Swaffham, Norfolk.

Ladislav Stojka, election of a Gypsy king.

Royal wedding celebrations.

The funeral of Private Lewis Hendry.

Battle of Britain Teatowels, Stroud.

Woman in a care home.

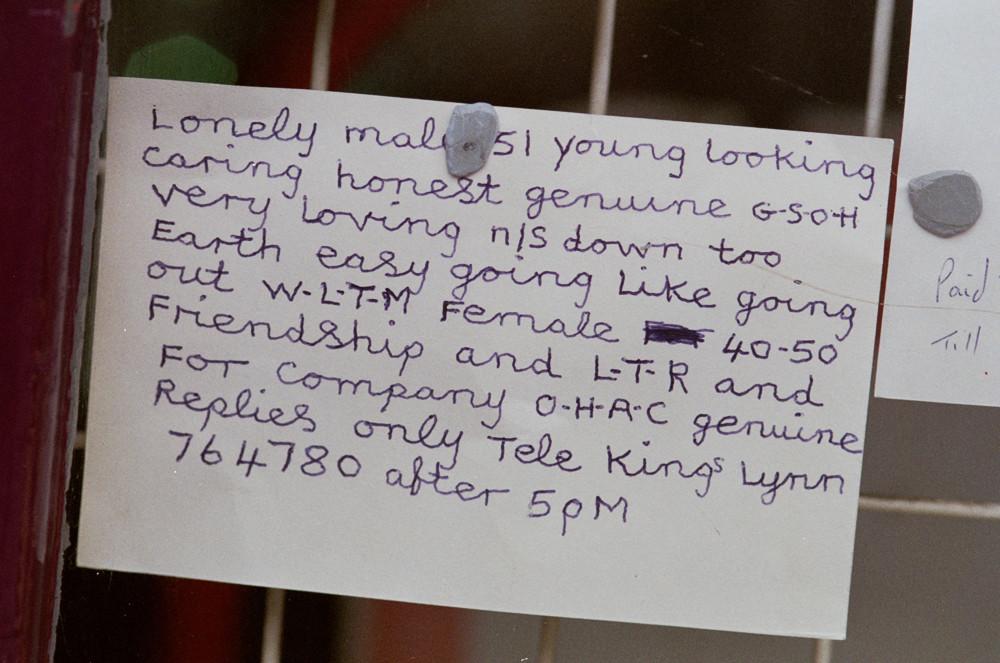

Doorstep moneylending advertisement in a newsagent’s window.

Cleckheaton, Yorkshire.

The Flower Queens, Spalding, Lincolnshire.

The money lender’s boy.

Julie, sex worker, Sunbridge Road, Bradford.

The Market Trader.

The Ageing Skinhead.

Heritage Day, Norfolk.

Discarded shoes, Aberfan, Wales.

Royal Wedding mural.

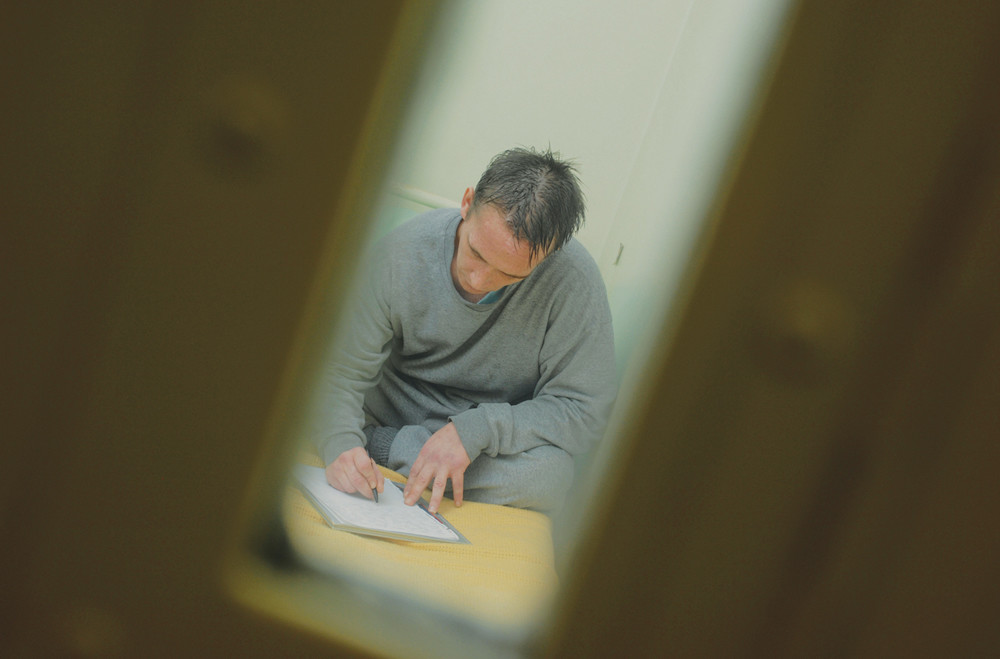

Writing home form Colchester prison.

The headmaster at Tollbar College, Grimsby searches students for weapons and illicit items before the school day begins.

Dani Filth fan with kebab outside Topshop, Birmingham.

A student graduates form Cambridge University.

Students from the Cambridge universities rest within the barricades to prevent eviction by the police as their occupation of the college enters its seventh day of protests against higher tuition fees imposed by the coalition Government.

The Straw Bear Festival, Whittlesey, Cambridgeshire.

Road accident memorial, on the A66, Cumbria.

Welcoming home the troops from Afghanistan. The body of Private James Grigg is conveyed into Stradbrook church Suffolk. The 21 year old became the 257th member of the British forces to die when he was killed by an explosion in Musa Qala.

Man with python on Blackpool Promenade.

A pilgrim trains with his cross in preparation for his annual walk to Walsingham.

Rod Stewart tribute artist Gerry Trew with a fan at Legends Nightclub, Batley, West Yorkshire.

Newsagents advert.