Paul Seesequasis, a Saskatoon writer of Willow Cree background and a member of the Beardy’s and Okemasis First Nation has been documenting the lives of Indigenous people living in Canada through a digital series of photos posted on Twitter. What started off as a labour of love and a visual testament of Indigenous resistance, has become symbolic of the power of social media to share marginalized stories, and also an avenue for Seesequasis to tell the history of Indigenous Peoples and highlight the strides made in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds such as racism, discrimination and state-sanctioned violence. Via Twitter, Seesequasis has crafted a lingua franca for marginalized voices and VICE sat down with him to talk about how his digital gallery began and the changes he hopes to see through this representation.

VICE: How did you get started sharing these images ?

Paul Seesequasis: It began two years ago in a discussion with my mother, who is a residential school survivor. She was reacting to media coverage on the radio and she longed to hear more positive stories about the Indigenous experience, in particular the strength of families and communities in admittedly hard times.

Videos by VICE

From there, I began researching and posting photos from First Nation Métis and Inuit communities, with a focus on a 50 year span up to the 1970s. These photos came from public archives, libraries, museums and local historical societies. It was a very engaging project and it generated lots of comments and feedback from followers on Twitter and Facebook. As it evolved, the engagement took on its own momentum with people naming relatives, locations or context to the photos themselves. In many instances, family members were not aware of the photos so there was also an act of reclamation in that.

Thematically, the photo feed was centred on resilience, resistance, and endurance.

It’s very difficult finding archives on any media platform that prominently feature Indigenous people. Has it been hard finding these images?

As I learned more in the process it became easier to locate the photos and also to identify the travels of certain photographers, time periods, and the photos they took. In many cases, these photographers built a rapport, a trust, and a place in the communities they were photographing. Those are the photos in which the process of freezing a moment in time can lead to intimacy, beauty and integrity of subject.

As well, there are Indigenous photographers like Peter Pitseolak (Inuk), George Johnston (Tlingit), and James Jerome (Gwich’in) who were early creators in the development of Indigenous photography.

One of my favourite pictures from your feed is the one of Mary Baillargeon & eagles. It’s a picture of a young Aboriginal girl standing alongside two giant eagles. It’s such an evocative and powerful picture. Can you tell us the story behind it?

The eagles were orphaned and found and raised by Alexie Crapeau and her brother, over 50 years ago. In the photo you are referring to, taken in 1956, by Henry Busse, the woman with the two, now grown, eagles, is Mary Louise Baillargeon (Dene). It is a breathtaking photo.

I also really like how your pictures show Aboriginal peoples doing what some might call the most mundane of activities. Why is this type of representation important to you?

The photos chosen represent day-to-day life. They often catch humourous moments or people at play, people at work or living off the land, or, they are facial portraits of elders or younger people in the communities. When I can they are named as listed in the digitized archival source, but in many cases they are not named. This is where feedback from followers has led to many subjects or situations being identified. And often there is a story, that is still remembered, that goes along with the story. There is a sense of urgency in this, as many of the contemporaries of people in these photos are now elderly, and when they are no longer with this, the stories these photos capture may also be lost.

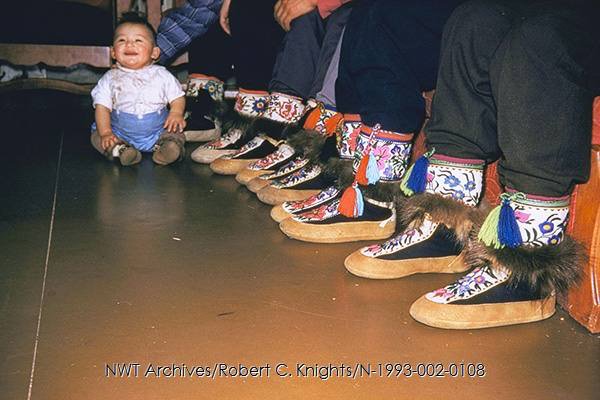

In the picture titled ‘Leslie Carpenter welcomes the New Year’ there is a young child sitting on the floor next to about 5 people, but all we see of them are their brightly coloured mukluks. There is so much cultural significance in that picture that speaks to Aboriginal traditions and that being passed onto the future. How are Aboriginal elders living in Canada ensuring that Aboriginal culture and traditions are not forgotten by the younger generation?

There is beauty in the child, Leslie Carpenter, but also in the craftwork of the mukluks which are a labour of love. It is a nice juxtaposition of the two and I do think it speaks to the endurance of familial bonds and of artistic and cultural practice. In some of the interviews I’ve done since this project began, many elders have talked about ‘the old ways’ and their hope that a new generation doesn’t lose this. Many communities are working at this, whether it is ways of living off the land, cultural camps, language (which is vital) and, in some cases, archiving elder’s voices, digitizing old recordings, or digitizing photographs. Many of these projects are under funded or done as a labour of love.

There should be more government support available for this but then the whole colonial apparatus and bureaucracy is still there. It is a tragedy that so many stories and so much language have been irretrievably lost.

Are you in touch with some of the people whose images you shared on your feed? People who were toddlers when the pictures were taken and are now in their adulthood?

Constantly. People who were children or teens in the photos and are now much older. Cousins and aunts and uncles of people in the photographs, and that is the most useful and rewarding part of the project. For myself, there isn’t a day were I don’t learn something new. That is both exciting and humbling.

What has the response been like?

The response has been very accepting and encouraging on social media. I hope it is a useful project in that regard. As we know, there is much darkness, misogyny and racism on social media. This project has felt very positive and I hope it comes across with the integrity and the respect I endeavour to put into it. Other than my own family photos, these are decidedly not my photos or my story to tell. They belong to the families and communities they come from. There is an open door of dialogue and I hope they feel this belongs to them.

Beyond that, there has been media coverage on radio and in print. I hope that whatever coverage this project warrants, that it also helps with things like Project Naming, which is the work of Indigenous archivists and local community projects.

Are you going to only focus on growing the digital gallery or do you also hope to have a physical exhibit of the pictures you have collected?

There will be a photographic book, inspired by the project, released by Knopf Canada in the spring of 2018. Other things may arise.

What methods of Indigenous representation would you like to see exhibited in mainstream media?

For the integrity and the diversity of Indigenous voices to be acknowledged and that mainstream media no longer relies on a few spokesmen, almost always men, to speak for all, which is both a false and impossible position. Also, more respect to women’s voices, Two-Spirit and youth. And most importantly, that there be more attention to the many excellent Indigenous media outlets and commentators.