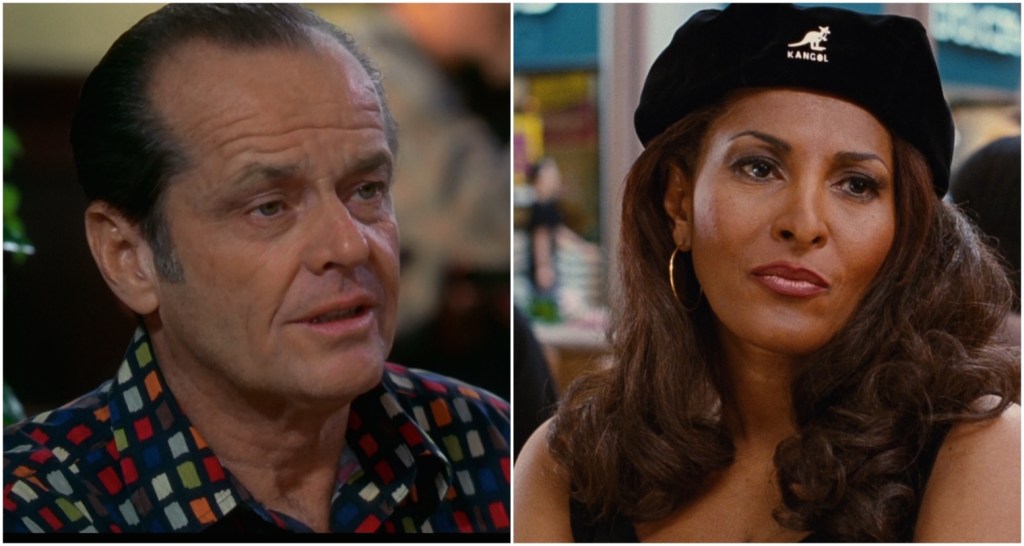

The fall of 1997 was, simply put, one of the most remarkable moviegoing seasons of our time: Boogie Nights. Jackie Brown. The Sweet Hereafter. Wag the Dog. Eve’s Bayou. Good Will Hunting. The Ice Storm. Amistad. As Good as It Gets. Gattaca. And so many more, culminating with what became the highest-grossing movie of all time: the long-delayed, oft-trashed, yet eventually unstoppable Titanic. Each week yielded another remarkable motion picture—sometimes two or more, taking bold risks, telling powerful stories, introducing formidable new talents, and reaffirming the gifts of master filmmakers. This series looks back at those movies, examining not only the particular merits of each, but what they told us about where movies were that fall 20 years ago, and about where movies were going.

The two major science-fiction movies of the fall of 1997, released two weeks apart, couldn’t have looked more different. Andrew Niccol’s Gattaca was a thoughtful hybrid of sci-fi, thriller, and character drama; to give you some idea of its high-mindedness, it not only opens with a relevant Bible verse (Ecclesiastes 7:13), but in the opening credits that follow, Gore Vidal is fifth-billed.

Videos by VICE

Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers, on the other hand, was a futuristic action cartoon, dramatizing a battle with giant space bugs; its gravitas was best summarized by the fact that its director’s previous film was the widely reviled 1995 stripper drama Showgirls. Yet both films proved more complicated than their marketing—and both would turn out to have much to say, and predict, about the future they were set in.

Gattaca takes place, per the opening titles, in “The Not-Too-Distant Future”; Mystery Science Theater 3000 had been on the air for seven seasons at this point, so draw your own conclusions. It imagines a world in which DNA testing has evolved to a point where one’s “genetic quotient” is the deciding factor of their station in life—to such an extent that nurses read out one’s life expectancy and chance of disorders in the delivery room. As a result, wealthier citizens engage in prenatal genetic engineering (“Still you,” as it is described, “simply the best you”) to ensure their children’s success. Those whose parents can’t swing it? Well, they can look forward to a life of menial work.

But occasionally, one gets through. Like any good futuristic storyteller, writer/director Niccol fleshes out his tale with terminology and mythology, so we discover that while Vincent Freeman (Ethan Hawke) is a “borrowed ladder”—an “invalid” who uses the identity of a “valid,” and the advantages it affords. Every morning, he undergoes the process of turning himself into someone else, genetically speaking; he scrubs off any scraps of his own skin and hair, prepares urine and blood samples, glues on fingerprints, and grabs a vial of dandruff, dirt, and the like. It’s working. He’s about to go up on a one-year manned mission to one of Saturn’s moons. But then a supervisor turns up dead, and the cops find a single eyelid that matches up to an “invalid”—him.

The shadowy photography, fedora-clad detectives, and innocent-man-wrongly-accused elements place Gattaca not in the future, but the past, recalling the great films noir of yesteryear. But there’s an ingenious twist: Vincent is an innocent man rightfully accused—guilty not of murder, but of an act of impersonation that, in this society, is perhaps as much a crime. And as in such stories, there’s a trusting woman (Uma Thurman), piecing together what he’s done while simultaneously falling in love with him. (There’s also some overlap with the Hitchcock heroine—and for the record, Uma Thurman would’ve made an excellent Hitchcock blonde.)

Yet for all the nostalgic echoes of its storytelling and production design, Gattaca felt very much of its moment. Just a couple of years earlier, the O.J. Simpson trial had properly clarified the concept of DNA for the handful of people who hadn’t seen or read Jurassic Park. As for the future, potential romantic partners doing hair-strand tests don’t feel that far removed from the match and compatibility algorithms of present-day online dating services.

But Gattaca‘s most compelling ideas are its most timeless ones. When Vincent’s boss compliments the quality of his work (“Not one error in a million keystrokes,” he beams) it recalls the kind of “work twice as hard,” Talented Tenth ethos that people of color have struggled with for centuries. When Vincent’s “ladder” Jerome (Jude Law) first meets him, his white-privilege bitterness shines through: “What makes you think you could be me at all?”

Jerome is hardly surprised when Vincent’s interview for his dream job consists entirely of a blood test; that’s how it works, because his blood is his birthright. And as our country buckles under the pressure of a white-supremacist president, who has bragged extensively about his “good genes” and whose children say he believes in the “race-horse theory” of eugenics, maybe Gattaca wasn’t that far-fetched after all.

Future Breaking Bad star Dean Norris pops up in a brief role in Gattaca, as a beat cop harassing Jerome; he has a much larger role in Starship Troopers, as the commanding officer of star Casper Van Dien, who bears the implausible moniker “Johnny Rico.” He and pals “Carmen Ibanez” and “Dizzy Flores”, played by equally white co-stars Denise Richards and Dina Meyer, live in a version of Buenos Aires that has apparently been entirely gentrified.

In its early scenes, Troopers is basically a goofy high school movie, complete with love triangles, a big game, and a school dance (and sex) after. But after graduation, our heroes sign up for “Federal Service,” assigned (perhaps via DNA?) to be officers, scientists, or in Johnny and Dizzy’s case, military grunts. Once they’ve begun infantry training, the flexing of machismo so over the top, it can only be satire; director Paul Verhoeven fills the movie with little winking nods, like Johnny’s video “letter home” that even includes a lonesome fiddler, a la Ken Burns’s The Civil War.

Verhoeven’s American crossover success began with Robocop, another big action movie with an unexpectedly wry perspective, and Troopers seems very much an attempt to recreate that success after the belly-flop of Showgirls (even if it turns into a boiler-place action/mission movie in the back half, as the back-to-back combat sequences grow more than a little monotonous).

Starship Troopers‘ best scenes are its funniest, echoing the corporate double-speak of Robocop‘s metropolitan dystopia; the film begins with a “Join Up Now!” military recruiting ad, complete with a little Hitler Youth kid (“I’m doing my part too!” he cheeses, as the rest of the troops chuckle-chuckle), and it’s sprinkled with witty parodies of WWI propaganda films, one of them cleverly titled Why We Fight.

But Troopers is also, in spots, weirdly prescient. The big attack that sends them off to war (“Goddamn bugs whacked us, Johnny”) is observed via a large group gathering, 9/11-style, to gawk at a television; the “countdown to victory” is captured via flashy, graphics-heavy news reports that look eerily similar to Fox and CNN’s coverage of the days that followed. (And we also get a glimpse of a Crossfire-style sneering-argument TV show, complete with a bow-tied, Tucker Carlson figure.)

Other elements are just as haunting. The militarism and fascism of the story, arguably embraced by Robert A. Heinlein’s original novel, is both questioned and tacitly embraced by Verhoeven’s (and his Robocop screenwriter Edward Neumeier’s) interpretation. In an early classroom scene, we—via a lecture to our heroes—are told, “veterans imposed the stability” of the current civilization (so, y’know, support the troops!) and it thus operates under an authoritarian dogma, wherein violence is “the supreme authority from which all other authority is derived.” And in that same scene, we learn that there’s a difference between “civilian” and “citizen” – as with Gattaca, some are created or considered “more equal” than others.

Thank goodness for fantasy escapism, am I right?