For some people, particularly those who follow the interesting history of the Canadian Football League, the venture into Sin City by both the NHL and NFL will bring to mind the Las Vegas Posse. The Posse, of course, were part of the CFL’s failed and short-lived US expansion era, lasting only one season in 1994 and proving that whatever happens in Vegas doesn’t always stay in Vegas.

It did, though, create a bunch of wild and crazy moments—both on and off the field. Those include a botched version of the Canadian national anthem that became an international controversy, team mascots that were horses that left more than their hoofprints on the field, scantily-clad cheerleaders performing halftime bikini contests, and one deceased Posse player getting selected in the dispersal draft after the team folded.

Videos by VICE

Defensive lineman Derrell Robertson, who was part of the Posse’s team but isn’t listed as having played any games, was drafted by the Ottawa Rough Riders in the dispersal draft. He had died in an automobile accident the previous December, though, and no one in the league office knew about it until it was reported.

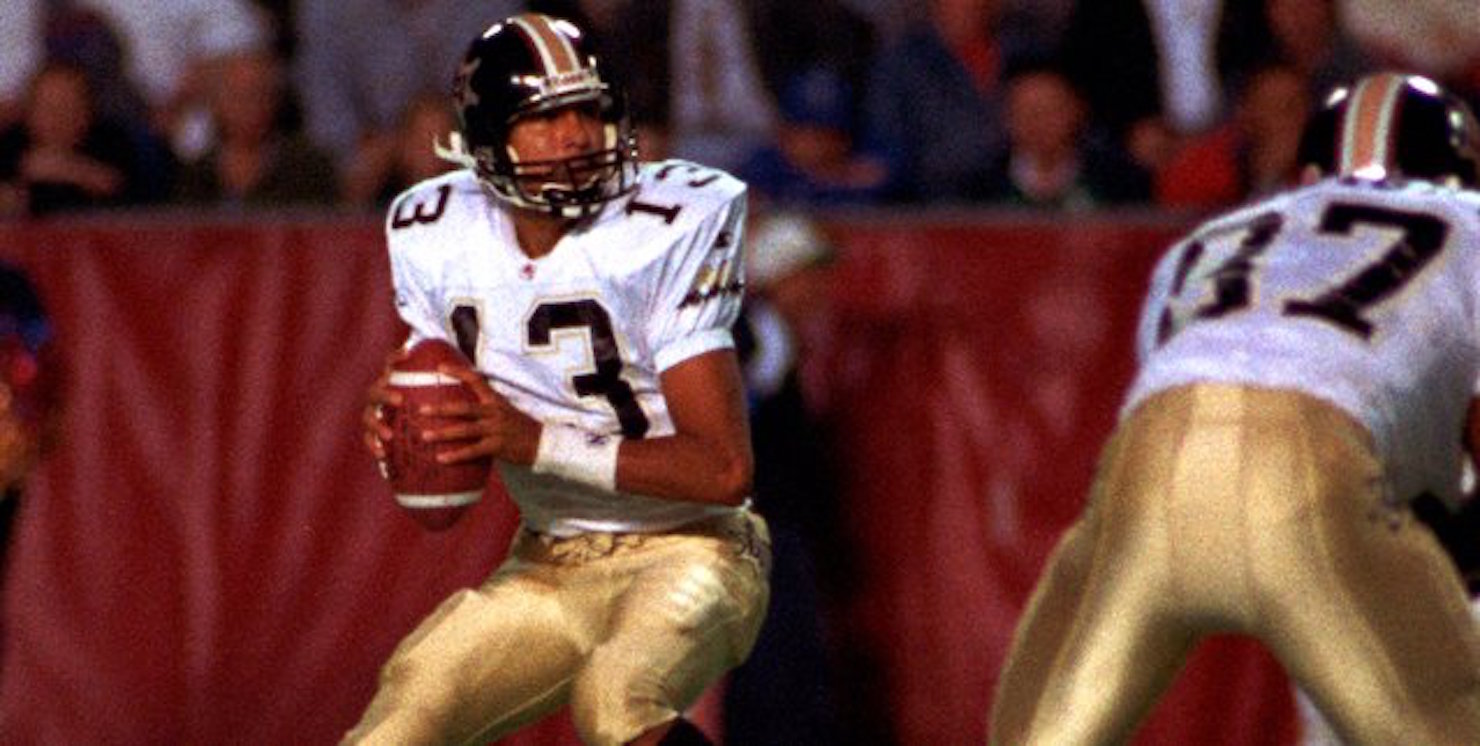

On the other side of all this, the Posse were the team to launch the career of Anthony Calvillo, a rookie quarterback who would go on to total a pro football record 79,816 passing yards in his 20-year CFL career. Calvillo and Posse linebacker Greg Battle were voted into the Canadian Football Hall of Fame after their careers ended. Kicker Carlos Huerta was the runner-up for rookie of the year honours. Special teams/linebackers coach Jeff Reinebold became a future CFL head coach, and Curtis Mayfield lived up to the nickname ‘Superfly’ by hauling in the most receiving yards in 39 years in one game.

What happened that year could be summed up as helter-skelter in the desert swelter.

“The end of the movie wasn’t that much fun, but most of it was really a blast,” Reinebold, now the defensive coordinator of the Hamilton Tiger-Cats, told VICE Sports. “It was such a unique thing taking a foreign game to another country. There’s stuff that went on that you just couldn’t believe. It was bizarro.”

Principal owner Nick Mileti, who at one point owned Cleveland’s Cavaliers and Indians, talked promisingly of having sufficient capital to finance the team, including some high rollers as investors. Ron Meyer, who had experience coaching at the University of Nevada Las Vegas and Southern Methodist University, as well as at the pro level with New England and Indianapolis, was hired as head coach. In the the end, none of that mattered, as the Posse were a one-and-done team, and the CFL’s USA experiment ended after the 1995 season.

Even still, and despite how different it was bringing Canadian football south of the border, Ron Kantowski, who covered the team for the Las Vegas Review Journal, said he was “fired up” about the team.

“This was our first foray into professional football,” he told VICE Sports. “It wasn’t the NFL, but it was a reasonable facsimile. I think there were a lot of people that were interested in seeing how it would it do here. It was legit football. They did the right thing. They brought in the right people, I think, the right coaching staff, certainly some good players. I remember when [the team] was announced, nobody said, at least not publicly, ‘This is going to be disaster. This has no shot.’ I don’t remember that being the case.”

Training camp provided the first snapshot of how different the Posse would do things. The team had two practices a day—the first during the morning at their home field, Sam Boyd Stadium, and the second taking place toward the evening at a grass field on the property of the Riviera Casino & Resort, where the team was headquartered during training camp. The field, which was only 70 yards long and did not have goalposts, had previously been a parking lot with yellow lines, and sported a large sign that read “Field Of ImPOSSEable dreams.”

Due to the extreme desert heat, Meyer allowed the coaches to go shirtless and barefoot in practices.

“All they had on was these little skimpy coaching shorts,” Kantowski said. “They weren’t even shorts. They were like the shortest you could wear without being arrested. The first time I went out there, I saw all the coaching staff kind of walking around like Tarzan on the practice field with the loincloth and no other clothing and all oiled up and bronzed up.”

One of the players the Posse signed was undersized middle linebacker David Maeva, who hadn’t played organized football on a regular basis since graduating from university four years before. The Posse liked what they saw of him in an All-Star Game for Hawaii-area players that year and he was overwhelmed by his initial pro experience.

“I was just a kid in a candy store,” Maeva told VICE Sports. “We’re not just in L.A., Miami—we’re in Vegas. There were guys from Florida State, Miami and I was just in awe of all of these guys. I remember seeing these guys on big-time TV. A lot of talent, but we were all learning this game of Canadian football. That was our downfall, too, because we didn’t truly know the game. Just no game knowledge.”

In their first preseason game, the Posse played in British Columbia against the Lions. Returner Tamarick Vanover, who had a two-year career at Florida State University before turning pro, signaled for a fair catch. He did not know there were no such rules in the CFL, and when the ball landed in the end zone the Lions pounced on it for a touchdown.

The Posse played their final preseason game at home, attracting a crowd of 6,280, and beat the Edmonton Eskimos 22-11. The Posse cheerleaders were Las Vegas showgirls who would on one occasion, at least, try to distract the visiting team, while the mascot was a team of horses, which was marketed as a huge selling point. There was a person assigned to shovel the horse droppings off the field.

Las Vegas opened its lone season with a 32-26 win over the Sacramento Gold Miners, another member of the CFL’s US invasion. The Posse returned to play their home opener eight days later in front of a crowd of 12,213, barely enough to fill half the stadium’s capacity of 31,000. Playing in a kickoff temperature of 104 degrees Fahrenheit, Las Vegas beat the Saskatchewan Roughriders 32-22.

But the game was overshadowed—and some would say this was a harbinger of the team’s downfall—in what became an international incident. Vegas singer Dennis Casey Park, who had been hired to sing the Canadian national anthem, completely botched it. He sang “O Canada” like “O Christmas Tree.” Park would recall many years later he had returned home from touring Japan and had been contacted to sing the anthem two days later. He memorized the words and the tune, but had no music to accompany him and had to deal with the echo of his voice. He started off OK and then completely flubbed it.

“I can remember standing on the sidelines with a couple of guys and we were just peeking over in the corner of our eyes and saying, ‘Oh my God, this is bad.’ You knew he was in trouble and it got worse,” Reinebold said.

The game aired on CBC, and two days later the snit hit the fan. It was such a controversy that the team received a nasty note from the office of the Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chretien.

In a letter to Chretien, Mileti said: “By way of explanation, but not excuse, this singer was recommended to us out of Los Angeles as a professional who had sung your anthem many times for the Olympics. Obviously, we were misled.”

Even US Vice-President Al Gore chimed in on the controversy while in Ottawa for a meeting with Chretien. Gore told reporters: “I was certainly glad to see that the US football players reacted so strongly and better than the singer.”

The Posse crumbled after those opening two wins, reaching the halfway point of the season at 3-6. “All of a sudden it went downhill really, really fast. We had wacko, wacko guys,” Reinebold said. “When it started to go bad, Meyer did an amazing job of holding the team together.”

Jeff Cummins, a defensive lineman, joined the team for the final half of the season after he was cut by the Cleveland Browns. He immediately sensed some different things such as practice beginning at 8 AM to avoid the heat.

“That was a whole different world for me,” Cummins told VICE Sports. “We were done with the practices by 12:30 [PM] every day. We had the rest of our time to live in Vegas, which was a whole different kettle of fish for a 24, 25-year-old. There were many times when players—and the names are not important—wouldn’t go to sleep [after a night out] and just go to the facility for practice. We’d been up all night.”

Players were told to cash their paycheques at the Riviera Casino.

“There was more than one or two times that we had guys that would go in there and start playing blackjack or craps or whatever and you’d see them the next day at meetings with a big, long face and you knew what happened,” Reinebold said. “They lost their whole paycheque in one night. That’s Vegas. That’s part of what you get when you go down there.”

The team won only two of its final nine games. The crowds dwindled as interest waned in the losing franchise. Attendance had plummeted to as low as 2,350 for what became the final home game against Winnipeg. It didn’t help that the heat made it extremely uncomfortable. It was so hot for one game, Maeva said he leaned on his helmet and the chin strap burned right into his skin, leaving a permanent scar.

“Coming from Hawaii, I wasn’t used to [that kind of heat],” he said. “That was a learning experience for this island boy.”

Cummins remembered that the team’s dwindling finances resulted in players not being given essential gear. He said he was among a handful of players who went to an army surplus store in Regina to buy cold-weather gear to make it through the season. He said the equipment manager was being “thrifty” and on one occasion he became involved in a dispute with a player and left the locker room.

“We had no equipment guy that day,” Cummins said. “It was nuts.”

Things fell into such complete financial disarray that the final home game against the Eskimos had to be played in Edmonton. The fans that had come from Edmonton to enjoy the Vegas experience weren’t allowed by the airlines to immediately change their return flights home, so they stayed and ended up watching the game on big screens in a ballroom of the Imperial Palace. The hotel trucked in Canadian beer to make the most of the situation.

“It’s what Canadians do—they drink their beer and have a good time. It was a lot of fun,” said Kantowski, who covered the game from the ballroom.

Three days after the season ended, Calvillo wondered if he would receive a bonus incentive cheque. He did not receive it until the following April, when the league paid Calvillo’s bonus and any other players who were due money.

“I always mention to people when they talk about [the Vegas experience], it opened up a lot more jobs in front of professional scouts and teams,” Calvillo told VICE Sports. “If it wasn’t for that, it probably would have been very difficult to get my foot in the door.”

Calvillo, now the quarterback coach for the Montreal Alouettes who kickoff the 2017 CFL season Thursday night against Saskatchewan, played in 17 games and recorded 154 completions in 384 attempts for 2,582 yards. He had 13 touchdown passes and 15 interceptions. He also rushed for 195 yards on 42 carries, which included two TDs and nine fumbles. Who could have predicted he’d be voted the CFL’s Most Outstanding Player three times, win the Grey Cup three times, and be voted the game’s MVP once?

“Anthony looked like a kid who all he really needed was a good meal, but in the end he becomes a Hall of Fame quarterback,” Reinebold said.

Through the benefit of his lengthy career, Calvillo can look back and realize the Vegas experience was truly different. He signed as a free agent out of Utah State, competed with a slew of quarterbacks, and slotted somewhere in the middle of the depth chart.

“You really didn’t know what to expect because every other day they were cutting somebody and I’m like, ‘My goodness, how can they evaluate these guys when they only had a few reps?’” Calvillo recalled. “It was very confusing at that time, but you know what, I didn’t know any different. It was my first experience, so everything I was experiencing that year was normal. The majority of us were either first year in the CFL or second year out of college. I don’t remember guys talking about, ‘This isn’t normal.’”

“It’s just one of those things where you realized some things were just not normal, like practicing in the parking lot of the Riviera Hotel and actually staying on the Las Vegas strip hotel for training camp,” he continued. “Those things kind of stand out for me now. Everything else was pretty much standard in terms of playing football.”

Kantowski has his own thoughts on what happened.

“It was hotter than a blast furnace and [they] were trying to play football in the middle of our hellish summer here,” he said. “They did everything they could. I think the biggest mistake, if you want to call it that, was the timing of the season, but it was really out of their hands. But it was kind of fun. Anthony Calvillo probably would have got his start somewhere else. It was cool to see what happened to him, so I guess we could take a little credit for that. I don’t know if that’s the right thing to do, but we will anyway.”

So, in the end, as bizarre and brief as the Vegas CFL experience was, it wasn’t all bad.

“It was an interesting year to say the least,” Cummins said. “My first three years in the CFL I won a total of nine games and lost 45, but for me to say that year was more crazy than the others, I don’t know if I can say that because I went through some interesting times—five different head coaches in two and a half years. It kind of added to the whole thing.

“That year in Vegas was crazy and nuts.”