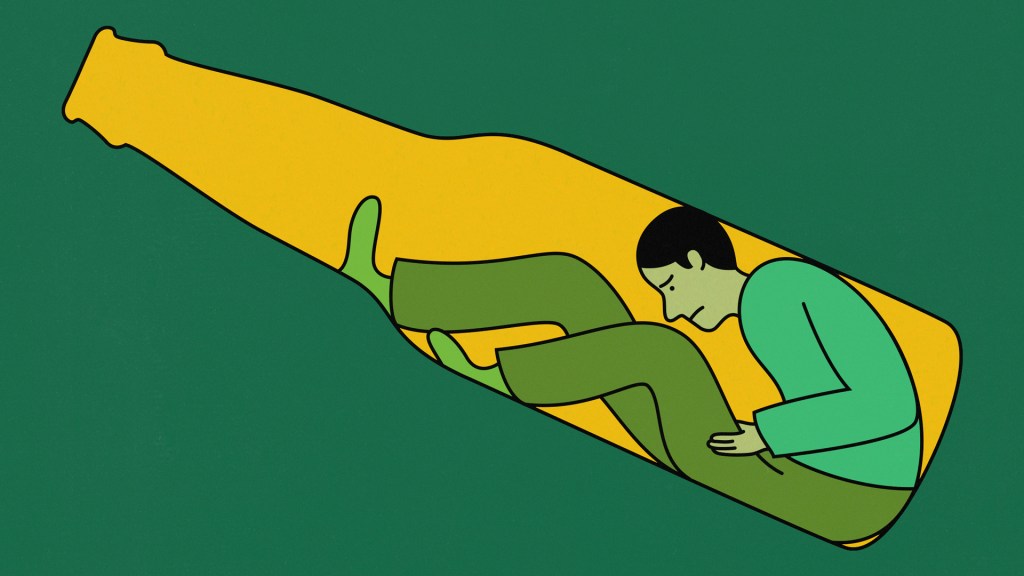

Isolation. Anxiety. Cravings. Not seeing friends. Worrying about an invisible and deadly disease. Depriving oneself of immediate gratification. Surrendering to the sheer magnitude of the situation. For many, this is a new post-COVID routine. For people with addictions in recovery, it’s a daily checklist that existed long before this global health crisis did.

Isolation can trigger enough introspection to cut through the carefully placed layers of internal bullshit that allow chaos and addiction to fester, but it can also trigger a relapse, especially when financial and mental health hang in the balance. This tension is inherent in sobriety at the best of times and becomes brutally obvious when self-isolation is a matter of life and death.

Videos by VICE

The tricky thing about isolation is that the usual checks and balances like AA meetings, work, or socializing are no longer in place. Without these outlets so readily available, a person in recovery has the freedom to get fucked up by themselves and watch the world burn with relatively little accountability.

As COVID poses a growing mental health threat worldwide, cranking up the volume on everything from anxiety to the risk of suicide, for many, it will be a make-or-break period in their sobriety.

We spoke to three people in recovery about what’s keeping them alive, healthy, and sober in a time of unprecedented isolation.

Matiya, whose last name we are not using to protect her identity as someone in recovery, has been in recovery since 2017 and is confronting the new reality of quarantine with mixed feelings. “It’s not the worst thing because we’re so prepared for it in recovery and so used to spending time alone, but at the same time it’s the worst possible thing for addicts,” she says after two weeks of isolating. “It’s really easy to slip when no one’s around, especially for newcomers.”

What usually keeps sober people in check is a combination of internal and external accountability, the latter having been seriously disrupted in recent weeks. “If you’re alone and you have nowhere to be, then why stay sober?” Matiya says. “No one’s watching. No one will know. In my experience, isolation is the biggest downfall for us because we’re not held accountable, we get lonely, and we lose a sense of community. It’s easy to slip when no one’s around. It’s really scary right now for a lot of people in recovery.”

Scary because, for Matiya, whose drugs of choice included heroin, cocaine, and alcohol, a relapse could be even more lethal than a virus with a two-to-three-percent kill rate. These baseline stressors are compounded by the fact that she has just been laid off from not one, but two jobs recently. Thanks to sobriety though, Matiya says she’s not feeling too overwhelmed.

“Honestly, it’s OK,” Matiya says. “The voice in my head is saying, ‘One day at a time’ and, as slogan-y as it sounds, it’s the way that I lived my life before quarantine and it’s the way that I live it now. I’ve been living with a disease that’s trying to kill me for a long time and I have a program (AA) that requires me to look at my daily life as unmanageable. At least I have tools to deal with this unmanageability.”

Those tools include daily meditation, prayer, and checking in with other people in recovery while benefiting from the explosion of Zoom meetings that have brought Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) out of the church basement and into the home in recent weeks. But in a community founded on fellowship and in-person meetings, the ripple effects of quarantine are still being felt hard.

Ryan Aronson is an addiction counselor and founder of Lighthouse Counselling Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Montreal. According to Aronson, an addict’s tendency to ruminate and obsess, especially when they are alone and under financial stress, puts them at a significant risk of relapse.

“The risk factors of mental obsession get exaggerated because there’s nobody to use as a mirror or to break you out of the hamster wheel of negative self-talk,” he says. “If you combine that with financial insecurity, it’s a recipe for disaster.”

And while the general population can still resort to the “essential services” of state-run liquor and cannabis stores to ease anxiety, many people in recovery are forced to confront discomfort head-on, though this is something they hopefully have trained themselves to do.

“Sobriety conditions you to be comfortable with the uncomfortable and to delay gratification,” Aronson says. “We’ve learned how to be on our own and find ways to survive and live without self-destructing or medicators or the need to constantly be eating, shopping, fucking, or whatever it is. The general attitude I’m hearing from our community at this time is, ‘Fuck, man, I’ve been through way worse; this is not my bottom. This is life on life’s terms, this is a roadblock, but I can handle this.’”

Marshall was laid off from his restaurant job two weeks ago. He’s also just reached six months of sobriety and at the moment is grateful for being more fixated on his phone than his old drugs of choice.

“I just got the gram—of cocaine. Just kidding!” he laughs. “Instagram—I’m just trying to figure out how to use Instagram for the first time. I haven’t really had any issues in terms of cravings or urges so far, thankfully.”

Bad social media puns aside, Marshall isn’t taking anything lightly. While he relied on in-person AA meetings in the pre-coronavirus era, he says regular check-ins with his sponsor and sober friends have alleviated the isolation he’s felt since, “You might be physically alone, but you’re not alone in terms of emotional connection.”

While Marshall may be a relative newcomer, any emotional discomfort he is feeling while in quarantine is far outweighed by the sense of gratitude he has for getting sober when he did. “If I wasn’t sober, I wouldn’t be handling anything right now,” he said. “I’m very grateful that I made the life changes when I did. I have a bit of a financial cushion right, because if I was still using I would still be completely dependent on my parents. Life would be very dark right now.”

With a daily routine centered around his mental health, Marshall says obstacles like isolation and unemployment are a lot more manageable than when his entire life revolved around cocaine and alcohol.

“I try to meditate first thing every morning and it helps tremendously to quiet the brain. I’m doing a lot of reading and staying occupied. I’m reading Harry Potter and walking for two hours every day—just going for a walk is fucking great. To normal people that doesn’t sound like much, but for me it’s huge. I’ve learned to find positivity in times when there’s a lot of negativity and uncertainty in the air and not fall into it. ”

Susil is a musician and recovering alcoholic who was also laid off from his day job as a bartender. Quarantine has been stressful, but accepting the harsh reality of a situation that is beyond his control wasn’t exactly a stretch. “It wasn’t too hard to surrender to this situation; I’ve already done that,” he says. “The first step in recovery is to surrender. Everyone is surrendering now, but surrender is its own form of control.”

Like Matiya and Marshall, Susil’s self-care regimen has been completely disrupted by COVID. “Meetings, sponsee work, gym, my actual day job, and playing music with people; those are my passions and routines and I can’t do any of them right now. But I’ve been sober for four and a half years right now, so I’ve got savings, so to speak, emotionally and financially, which I’m grateful for because it’s definitely not a good time to relapse right now.”

In many ways, recovery is a form of emotional prepping where—instead of canned goods and toilet paper or drugs and alcohol—introspection, gratitude, and a few handy AA slogans are stockpiled in anticipation of the inevitable chaos of life. Every person I spoke to for this article emphasized that the key to staying grounded in quarantine has been to reach out to others via one-on-one phone calls or Zoom meetings; reaching out not only to help themselves, but to help others.

“I’m working with a newcomer now and she is so afraid to say that she’s having cravings, because she feels like she’s failing at recovery,” Ryan Aronson says. “Everybody is talking about how well they’re doing in recovery and she feels inferior and uncomfortable saying, ‘I feel like using.’”

For someone in recovery, being alone is nowhere near as dangerous as feeling alone and feeling alone is something that can only be alleviated by reaching out for help. For Matiya, who’s relapsed twice since being in recovery, the thought of dealing with substance issues in isolation—without the safety net of self-care and community that she’s woven in recovery—is terrifying.

“Even though it’s crazy out there, all of us who are suffering or have suffered are still getting together and doing what we can to make sure that we’re all OK.” Matiya says. “Still, not everyone has access to Zoom meetings or solid footing in a program that allows for phone calls and community. When I think about someone going through this alone, it’s really scary, because Coronavirus likely won’t kill you, but relapsing will.”

Follow Nick on Twitter.