Mosul, the largest city under the control of the Islamic State group, has been liberated, and Raqqa, the group’s administrative capital in Syria, is set to follow soon. The Sunni extremists’ attempt to govern a caliphate has failed — but it’s far from the end for ISIS.

The infamous terror group has lost more than half of its territory in both Iraq and Syria, and most of its revenue-generating capacity since 2015, along with the claim of being a functioning Islamic state that can command the loyalty of Muslims around the world. But the group, which sees itself as waging an existential battle against all non-believers, has been preparing for these inevitable losses for some time, adapting its messaging to convince followers for a continued fight beyond the fall of a physical caliphate, analysts told Vice News, and launching affiliates elsewhere in the world.

Videos by VICE

“There’s a misconception that the fall of these territorial holdings means the group will dissipate — that’s just not the case,” Matthew Henman, head of Jane’s Terrorism and Insurgency Center, told VICE News.

Henman says that even without territory to govern, ISIS will continue to operate in the shadows as a significant insurgent threat in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere, and will continue encouraging terror attacks in the West — in no small part to “avenge” the loss of the caliphate.

“They’ve created this narrative of victimhood and revenge,” said Henman. “‘We created the caliphate, yet this international crusader-led alliance has crushed it brutally — and you can take revenge for us.’”

Still, the liberation of Mosul and the impending retaking of Raqqa are major blows for ISIS. Mosul is Iraq’s second-largest city, and occupying it brought considerable prestige and revenue to the terror group, with its nearby oil fields providing a constant movable commodity. The city’s medieval al-Nuri mosque was where ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi proclaimed his caliphate on July 4, 2014, making the loss a symbolic hit to the group’s legitimacy.

ISIS is running low on money

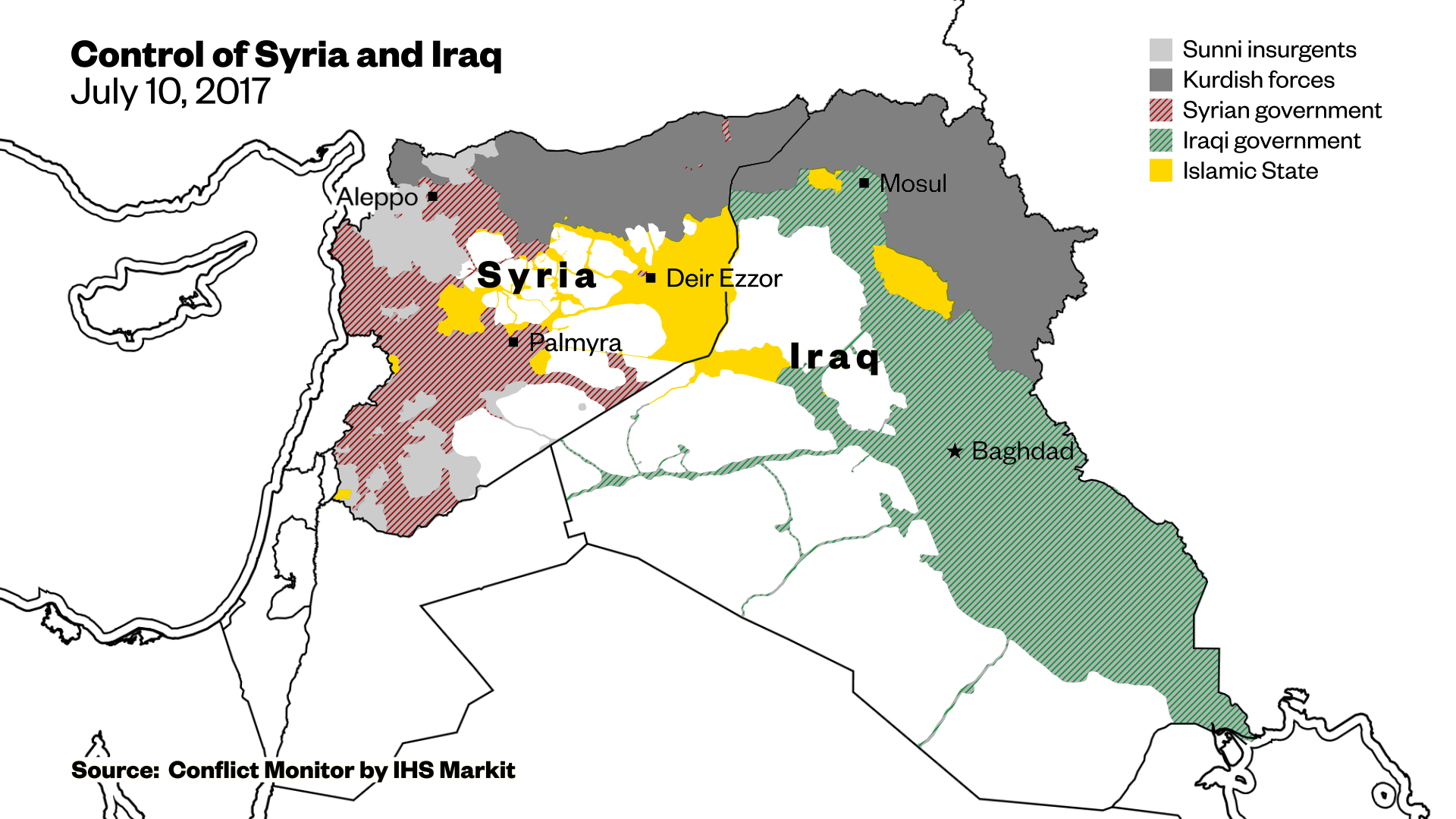

According to analysis done by IHS Markit’s Conflict Monitor, the U.S.-backed military campaign against ISIS has shrunk the territory under its control by 60 percent from 90,800 square kilometers in Iraq and Syria in January 2015 to an estimated 36,200 km2 — an area roughly the size of Maryland or Belgium.

That loss has hit the group in an area that once distinguished it from its competitors: money. The Islamic State’s average monthly revenue — predominantly derived from oil, taxes, and confiscations — dropped from $81 million in the second financial quarter of 2015 to an estimated $16 million in the second quarter of this year.

Still, ISIS retains significant territories concentrated in areas of eastern Syria and western Iraq — towns like Tal Afar in Iraq and Al Bukamal in Syria, but also large tracts of desert terrain under its effective control. It has a heavy presence in areas around the eastern Syrian city of Deir Ezzor, where many of its senior figures are reported to have relocated in recent months, becoming something of a new stronghold for the group.

Anti-ISIS forces will pursue them in these areas next — but fully liberating an area from ISIS can be next to impossible, as militants can simply disguise themselves among refugee flows and return when the fighting stops.

“Even if every last bit of territory is captured from the group, the threat doesn’t go away,” says Henman.

As ISIS reverts from being a territory-holding state to a guerrilla insurgency, its members are slipping into the shadows, going underground in urban areas or hiding out in ungoverned stretches of desert where they can plot and launch attacks, experts warn. According to a report by the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, there have been nearly 1,500 ISIS attacks in 11 Iraqi cities and towns and five in Syria after they were liberated from ISIS.

Insurgents again

For ISIS, this insurgent methodology is old hat, and they have a proven track record at it, analysts warn. This was how the group operated in the years after the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq, wreaking havoc with coordinated attacks across the country before exploding into the international news agenda with its declaration of a cross-border caliphate in 2014.

“They’ll try to incite hatred, they’ll try to tip the balance in a very fragile society toward escalation,” Andreas Krieg, an assistant professor in defence studies at King’s College London, told VICE News.

Their objective would remain to exploit sectarian tensions between Sunni and Shia, both analysts said. And while ISIS decidedly lost hearts and minds among the populations brutalized under its rule, the underlying tensions in those communities — Sunni grievances against Iraq’s Shia-led government, opposition to Syrian President Bashar Assad’s brutal regime — remained unresolved, and fertile territory for the group to exploit.

The caliphate goes global

Though the loss of territory is no doubt a blow to ISIS’ overall operations, its sophisticated propaganda machine has adjusted to prepare for the eventual loss of Mosul and Raqqa, and has been signaling to sympathizers that the battle will continue unabated. Before his death in a drone strike last year, ISIS spokesman Abu Mohammed al-Adnani said the loss of the cities would not spell the end. “Defeat is losing the will and the desire to fight,” he said.

ISIS has long instructed its sympathizers in Western countries to launch attacks at home if they could not travel to the caliphate. With the demise of the physical caliphate, analysts say to expect such attacks to escalate as sympathizers focus on striking the “crusaders” at home — where their attacks are likely to resonate with a greater impact than they would on the bloody battlefields of Syria or Iraq.

“At the end of the day ISIS is a narrative, it’s an idea. The idea will never be beaten by military force.”

“The message to stay and attack Western society is stronger than ever,” said Krieg. The threat could come from sympathizers radicalized by ISIS online propaganda — the output of which has persisted despite the group’s military struggles — or by foreign fighters returning home, hardened by battlefield experience.

The loss of strongholds Mosul and Raqqa also places an increased focus on the terror group’s other “vilayats,” or governorates, in Libya, Sinai, Afghanistan, West Africa, the Caucasus, and the Philippines. Some foreign fighters have taken up the group’s encouragement to join jihadi efforts elsewhere — such as in the southern Philippines, where ISIS-aligned forces have seized the city of Marawi — rather than attempting to travel to Iraq and Syria.

The governorates are “going to become increasingly important,” said Henman. “They’ll look to follow the same methodology as in Iraq to create the conditions where they’re able to seize territory. This is a problem that has spread far beyond Iraq and Syria now.”

The great risk, he said, was that the international community would say “mission accomplished” after the fall of Mosul and Raqqa, and thereby create the space for ISIS to operate under the radar (see al Qaida) to eventually re-establish its caliphate, as it undoubtedly will seek to do.

“They’re very clear that this is a minor setback in the eventual path to victory they believe has been promised to them by Allah,” he said.

Krieg agreed, saying despite the military victory in Mosul, ISIS could only be defeated on an ideological battleground — an area where efforts against the group have failed to gain much traction.

“At the end of the day, ISIS is a narrative, it’s an idea,” Krieg said. “The idea will never be beaten by military force.”