Ever since former premier Christy Clark stepped out of the public eye earlier this year, British Columbians haven’t been hearing too much about the liquified natural gas sector her government built and subsidized. What seemed like a lot of bragging and bending to international investors a few months ago has been replaced with Premier John Horgan’s much quieter investment pursuits.

Now a pilot study from Université de Montréal researchers has reminded us there’s still a lot we don’t know about shale gas extraction in northeastern BC. Specifically, there’s not a lot of science digging into how fracking-related chemical exposure in the region might be impacting local people’s health.

Videos by VICE

Élyse Caron-Beaudoin is a postdoctoral fellow and coauthor of a new pilot study that aimed to fill this “data gap.” The study builds on American research that found fracking and other oil and gas development releases volatile organic compounds like benzene into the environment.

Fracking is the process of injecting massive amounts of water mixed with chemicals at high pressures into shale rock formations hundreds of metres below the surface. Elyse told VICE that companies don’t have to publicly disclose exactly what chemicals they are mixing, and that toxicity data doesn’t exist for hundreds of them.

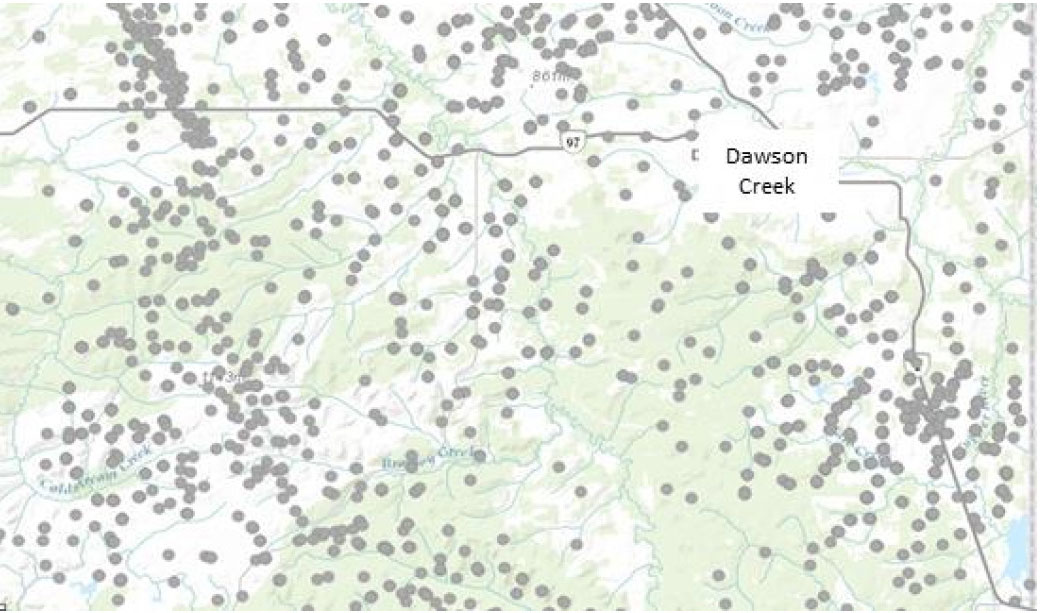

The researchers tested urine samples of 29 pregnant women in Chetwynd and Dawson Creek, two small communities near heavily-fracked shale gas fields in BC’s Peace River Valley. They measured two “biomarkers” that our bodies produce when we’re exposed to benzene, a carcinogen that’s been linked to low birth weights and some defects.

Caron-Beaudoin told VICE benzene is a byproduct of any combustion—so smoking cigarettes or driving around the city will also cause some exposure. But the research findings, which will appear in the January issue of Environment International, suggest that exposure levels in these remote communities fall outside what’s normal.

Caron-Beaudoin says her team found the women’s urine samples had 3.5 times more of these biomarkers than the average Canadian. Of the women who identified as Indigenous, those markers were six times more concentrated. But because the sample size is so small, the authors say more research is needed to be sure benzene is really the cause.

The researchers chose benzene biomarkers because the Canadian government already has solid data on it, and it’s much easier to test for than benzene itself. “Because benzene is volatile and those tests need to be done quickly, we decided it’s not possible to measure benzene directly in urine,” Caron-Beaudoin told VICE. “With those little molecules it’s easier to freeze the samples and analyze later.”

But, Caron-Beaudoin says this isn’t a perfect indicator, because some food preservatives also create the same biomarkers when our bodies try to break them down. “It’s not 100 percent specific to benzene, but it gives a good idea,” she said, adding diet or second-hand smoke exposure alone were unlikely to account for such high concentrations of the markers.

Caron-Beaudoin said more research is needed to determine how much benzene is present in the area’s air and drinking water, and how much of an impact that’s actually had on pregnancies. Her team is already planning to spend the next two years digging into 6,000 birth records to see if any local trends emerge.

“What we will do, is we will look at associations between density and proximity of fracking wells and some birth outcomes in the past 10 years in northeast BC,” she said. “So looking at birth weight, gestational age, which gives an idea of preterm birth or not, head circumference, and birth defects.”

When complete, the study will be the first of its kind in Canada.

Follow Sarah Berman on Twitter.