Sign up for our new VICE News Canada newsletter here

Isaac Murdoch has always felt a deep connection to the land.

Videos by VICE

The Anishinaabe teacher and storyteller was raised in Serpent River First Nation, in Ontario, and learned from his family and community teachings how to live a traditional life of hunting, fishing, and ceremony.

It’s a connection that he has been able to cultivate and shelter, despite the odds being stacked against him and his people in a country that has systematically sought to strip culture and identity away from Indigenous communities.

So when the festivities and fanfare of Canada’s 150th birthday celebrations geared up this year, he turned to that which has kept him grounded, creating a camp designed to pass on Indigenous knowledge to youth.

Nimkii Aazhabikong, meaning Village of Thunder Mountain, is a counterpoint to Canada’s Indian Act, which was created to contain Indigenous peoples on reserves and assimilate them into mainstream society.

“It’s the resurgence.”

“We’re having young people engage with their elders, we’re taking land back, we’re also using our traditional forms of government, and it’s going good,” said Murdoch, who founded the camp with Michif artist Christi Belcourt.

“We’ve got a great response from the local native communities, we have full support by the chiefs and elders, so this is how we’re actually resisting. It’s the resurgence.”

It’s one of the ways in which Indigenous communities are rejecting the celebration over Canada’s 150, and seeding a counter narrative into the public consciousness. From poster campaigns, pointed published critiques, social media movements, theatre productions, musical revelries, poetry and more, Indigenous leaders and artists have been fighting back by showing non-Indigenous people why it’s important they know what they’re celebrating. It’s a relatively small effort, when compared to the $500-million being poured into Canada 150 festivities by the federal government, but people are taking notice. Earlier this week, the National Farmers Union threw its support behind a national day of action by Idle No More, an Indigenous sovereignty movement founded in 2012.

“We call on the Liberal government to take swift action to resolve land claim disputes and violations of Indigenous treaty rights, and to rein in extractive industries whose projects threaten the well-being of Indigenous peoples in their territories,” the union, a voluntary organization, stated.

Early Thursday morning, a group organized by Idle No More erected a teepee at Parliament Hill in protest of the Canada 150 celebrations, but only after police arrested and detained some of the protesters.

The activism comes at a time of heightened awareness of the problems and discrimination still faced by First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people in Canada. Dozens of reserves haven’t had clean drinking water for years; several communities have declared states of emergencies over a wave of suicides by youth, and an inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls has been fraught with delays.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has said that “no relationship is more important to me and to Canada than the one with Indigenous peoples”, and called for a renewed “nation-to-nation relationship.” But two years after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission laid bare the damage of the residential school system, which forcibly removed Indigenous children from their homes for over a century, placing them in government and church run boarding schools, a host of recommendations aimed at addressing the traumatic legacy have yet to be implemented.

“Today, more Indigenous children are taken from their families — now put into foster care — than at the height of the residential schools cruelty,” Mi’kmaq citizen and lawyer Pamela Palmater wrote in a recent edition of Now Toronto. “The over-incarceration of Indigenous men, women and children continues at alarming rates. Even though Indigenous people represent only 4 percent of the population, some prisons contain nearly 100 per cent Indigenous inmates.”

It’s to this backdrop that Cree artist Kent Monkman unveiled his exhibit at the University of Toronto Art Museum in January titled Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience.

His painted images are a story that starts 150 years before confederation, and combines historical paintings and artifacts alongside his own work. One piece, entitled “The Scream,” depicts the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and nuns prying Indigenous children from their homes in order to send them to residential schools.

Coinciding with Monkman’s portrayal of Canada 150 is #Resistance150, a project showcasing the ways Indigenous peoples have resisted and continue to resist the policies of the Canadian government. It was started by Belcourt; Murdoch; Tanya Kappo, a Cree activist and advocate; and Maria Campbell, Métis elder and author.

For Murdoch, seeing how Indigenous peoples are reacting to the resistance of Canada 150, either through art or simply speaking out, gives him a sense of pride in the resilience of his peoples.

“We’re saying you can’t do this to us anymore, your celebration stinks, it’s built on genocide.”

“For a while there it was kind of like — did we actually get absorbed into the Canadian politic and mainstream society? Is there any fight left? Did the Indian Act actually accomplish what it was set out to do in 1867?”

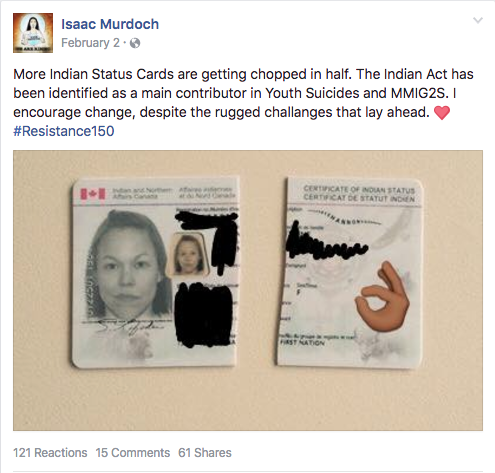

He’s been impressed by the strong response to his recent art project asking First Nations people to mail him their status cards. The cards identify someone as a registered “status Indian” under the Indian Act and make them eligible for certain rights — such as tax and gas benefits — that are not available to other Indigenous peoples.

Murdoch says that the cards represent the ways in which the Act has been instrumental in “containing Indigenous people on the reserves and enforcing colonization on our people.”

And doing away with them is one way to enact resistance, he said. He’s received dozens of cards, as well as Métis cards and even band membership cards from Native Americans in the U.S. — from grandmothers to teenagers.

“To see this resistance for me, it’s like we’re rising up for our land and waters,” Murdoch said of the broader efforts. “We’re saying you can’t do this to us anymore, your celebration stinks, it’s built on genocide, and we’re moving forward to a new era where Indigenous people have land and where we have our rights in our nationhood.”

It’s not only social media and the arts that have resisted the celebration of Canada 150.

Quinn Meawasige, a community economic and social development student at Algoma University in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, has successfully stopped the celebrations his school was going to have — in an institution that used to be a residential school.

“The university was planning to do some celebrations on site and we were like, ‘you know what? No,’” said Meawasige.

“[It’s] one of the only universities in Canada which is located on a site like this. It has a very unique, special responsibility and commitment to reconciliation.”

For Meawasige, it’s important for people to see the opposition.

“If people didn’t see Indigenous people resisting, they would think that we are okay with the status quo. Business would continue as usual, there would still be ongoing discrimination, racism, colonialism … people need to know that we are not okay with this,” said Meawasige.

“If we don’t, things will never change and it will always be status quo and I don’t think our grandchildren can afford that. Our future generations can’t afford that, these kids who are committing suicide who are hopeless. I don’t think they can afford that.”

“The key word here with me and with other people is the term participation — not celebration. “

On the other hand, there are other Indigenous peoples participating in the celebration, but doing so with specific intent and meaning.

Kenneth T. Williams, George Gordon First Nation member and Cree playwright, said he was “indifferent” to the celebrations and is instead using money allocated by the government for the festivities to create a play about Canada’s history from an Indigenous perspective.

“For me, I have to participate in these things because otherwise our story gets lost. We need to ensure that if you’re going to tell any story about Canada, that the Indigenous stories are included and they must be there — stories about resistance and resilience have to be told. It’s through the arts that a lot of people get their information,” said Williams.

“I totally support people who want to boycott, who want to actively boycott, who want to encourage others to boycott, I’m totally on their side on that, but my point is we need to keep in there and keep agitating and telling our stories.”

Drew Hayden Taylor, an award winning playwright and novelist from Curve Lake First Nation, wrote a play about Canada’s first Prime Minister Sir John A. MacDonald, at the request of the National Arts Centre.

“I thought this would be an excellent, excellent, excellent opportunity to explore this man, his wanted achievements, this hero worship of him as a founding father of Canada, but again, through the lens of Aboriginal perspective,” said Taylor.

Though Taylor is a part of the celebrations, he remains adamant that he is participating and not celebrating the event.

“The key word here with me and with other people is the term participation — not celebration. If this is going to be a representation of Canada, a development of Canada, over the last 150 years, such a celebration would reek hollow without some Aboriginal participation.”

With files from Rachel Browne