If you walk down a side street about three minutes from central London’s Holborn Station, you’ll come across this seedy strip joint called The Red Rooms. It looks unassuming. The front of the building is crossed with metal bars until 10PM. No posters or flyers hang on to the concrete walls outside. And the entrance, a small, mirrored door on the right-hand side, looks like it leads to someone’s flat. I have no idea who goes there now, or what the decor is like inside, but exactly four decades ago this same building had a huge neon sign above it that read ‘The Blitz’. And if you were young and liked dressing up, it was the place to be on a Tuesday night. Now let’s rewind.

In 1978, west London looked nothing like it does today. Pret A Mangers and Apple stores didn’t punctuate every other street like a full-stop. The pubs and clubs, now heaving with red-faced yuppies and exhausted shoppers, were instead filled with queers kids, soul boys and fashion students from nearby Central Saint Martins and Central School. For a short while, punk had been a dominant youth subculture in the area, but in the months leading up to Sid Vicious’ death, interest in that music and style had begun to wane. A lot of young people had grown bored of listening to aggressive, macho guitar music and wearing shitty DIY clothes. They wanted to dress up and paint their faces in flamboyant colours and dance all night to synth pop. And so, at the turn of the decade, that’s what they started doing at The Blitz.

Videos by VICE

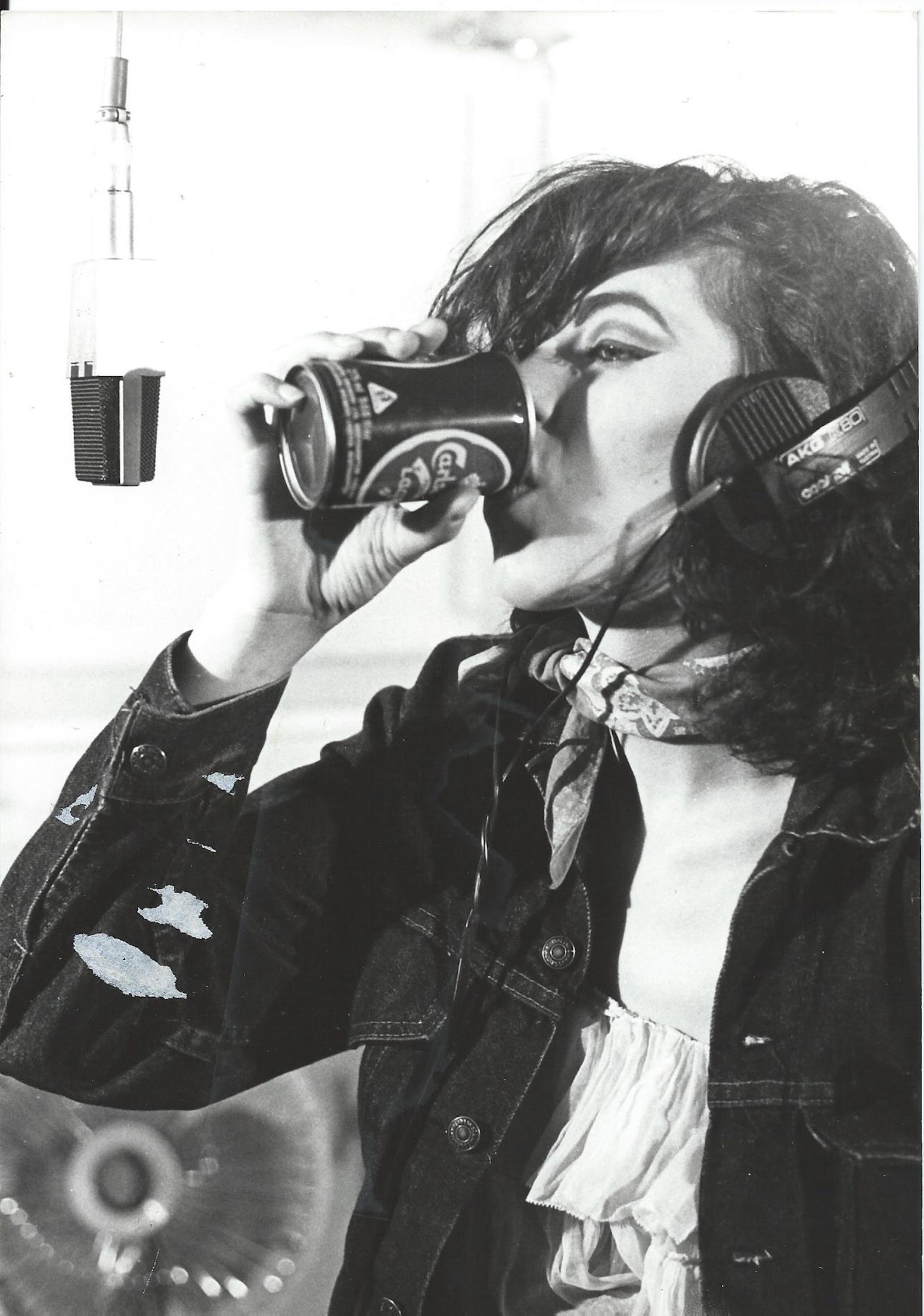

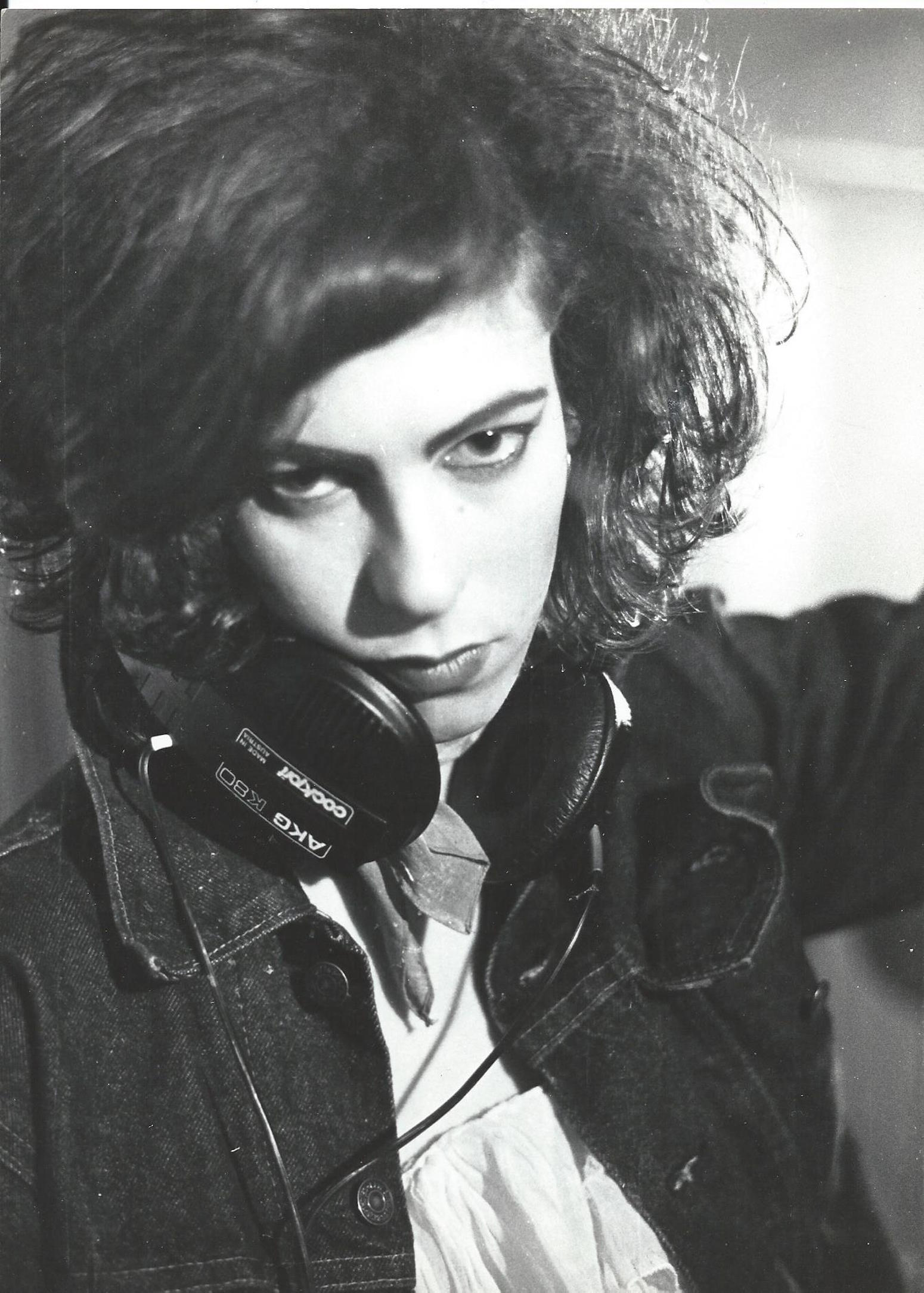

One such person was Rex Nayman, then a 19-year-old fashion student who lived in the suburbs. Every Tuesday night, she would backcomb her hair into a giant nest, paint her face chalk-white and take the train into London to hang out at The Blitz and another bar in Kingston alongside not-yet-famous locals like Boy George, Princess Julia and Steve Strange. One night, during one of these excursions, she was approached by a keyboardist called Vic Martin. He’d been searching for someone new to make music with and liked the way Rex looked, with her unimpressed expression and over-the-top, new romantic outfits. “Do you want to make a record?” he asked her straight away, unsure if she’d ever sang, or would even want to start. She hadn’t and didn’t, but agreed to it anyway for something to do over the summer. They called themselves Rexy.

I first heard Rexy earlier this year, right in the heavy gloom of winter. My friend and I had been chain smoking indoors all evening, methodically working our way through her stack of records while huddled around a portable heater on the bedroom floor. When Rexy came on the speakers, I vaguely assumed they must be a new band, something someone’s friend had made recently, perhaps in the style of an older era. They seemed strange to me, Rex’s totally unaffected voice floating over fizzing synths that were like UFO sounds from an old movie. One moment would be crammed full of catchy hooks, the next lo-fi and off-kilter, with lyrics that spoke of paranoia, outsiderism, surveillance, anarchy. But when my friend told me they had actually just made this one album in 1981, Running Out of Time, before parting ways for 30 years, my interest was piqued even further. I wanted to know more.

Apparently I wasn’t the only one. Last year, New York musician Samantha Urbani (Blood Orange collaborator, formerly of band Friends) re-issued the ten-track album on her label URU in conjunction with Lucky Number. Running Out of Time had already gained a small cult following over the years, but Urbani wished to celebrate it further, describing it in a press release as “a companion that understood me” and as “something truly punk, truly individualist, in that it was purely itself”. Following the re-issue, various artists released covers of Rexy songs, with Urbani, Nite Jewel and Zoe Kravitz recording their version of “Don’t Turn Me Away”, Ariel Pink and Puro Instinct covering “In the Force” and Connan Mockasin releasing “Running Out of Time”. I spent the next few weeks listening to all of them, back-to-back, repeatedly finding myself disappearing down a late night Rexy hole. The covers were cool, but I was most drawn to Rex herself. Who was this person, and why did I relate so strongly to this album from nearly four decades ago? I decided the only way I’d ever find out would be to meet them both.

After successfully tracking Rex and Vic down via Lucky Number, we arrange to meet outside the former location of The Blitz. I’m not sure who to look out for: neither of them have any public pictures online other than ones of Rex from the time, and at this point they’re both well into their fifties. But when I see a woman with huge hair, red lipstick, a Vivienne Westwood shirt and a long teddy coat, followed by a very tall man in leather, I know it’s them. “It’s horrible round here now init, totally corporate,” Rex says to me in exactly the same bored, idiosyncratic voice that appears on Running Out of Time, rolling her eyes and laughing. After strolling and staring into the windows of a few pubs rammed with white men in business suits, we finally settle on a neon blue-lit hotel bar blasting out Vengaboys’ “We’re Going to Ibiza!”.

I ask them how they made the record, where they were, what it was like. “It was so long ago… I can’t really remember,” Rex says, scrunching up her nose and sipping on a diet coke. “But I do remember being shit scared because it was totally new to me; I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. Basically I couldn’t sing, so I had to practice speaking before we went into the studio to record.” Vic jumps in: “We recorded the first single, ‘Don’t Turn Me Away’, down the road from The Blitz in this damp basement studio below a record shop. We used to drink a lot in those days, and it stank down there. But it was cheap. The record label [Alien Records] were also skint, so the whole process was like pushing boulders uphill.” Even so, that first single went on to be relatively successful and even received some airplay on BBC Radio 1 at the time. “It was very exciting hearing it on the radio,” Rex says. “I was doing my fashion degree and I remember it playing while I was working and being like, ‘oh my god’.”

Once they’d released that first single, they tell me, they made the rest of the album, recording it in snatches during evenings and weekends when Rex wasn’t studying. But after it was out there, they decided not to continue. “It just wasn’t the success we’d hoped for… and it wasn’t worth me leaving college. We got about £6 in royalties each,” Rex explains, shrugging. Vic continues: “There’s more interest in us now than there was then, I really don’t get it, I don’t understand where all this has come from…?” They both look at me blankly, as if to provide them with some sort of answer. I don’t know what to say. I try to explain how, even though I was born a decade after this album was made, I still relate to its grey, anarchic vision of London, it’s weirdo spirit. “So you wanna be alien too, huh? / So you wanna be alien too,” sings Rex on “Alien”, like an outsider looking in, amused at a world they don’t understand. I love that song. They still look confused.

After Running Out Of Time, the two of them gradually lost touch. They still saw each other now and then at clubs in the early 80s, but in 1983 Vic started touring with other bands, and Rex became a fashion designer before moving onto pattern cutting. For a long time, neither of them listened back on what they’d made together. “I’ve got the original vinyl, but my record player is knackered, so I hadn’t listened to the album for years,” Rex tells me. “Some of the songs I’d even forgotten how they went. Then when it started getting interest again, and people started putting old recordings on YouTube, I don’t know if I liked it or not… it’s so hard to be objective about your own stuff. You always think ‘Oh god, this is embarrassing.’ It makes you cringe.” As for the two of them, they started chatting again ten years ago. “When I joined Facebook in 2007, one of the first people that pinged up was Vic saying ‘Hello!’” Rex says. “I’ve reconnected with a lot of people from that time through Facebook, and seen some of them too. I like it for that.”

I can’t tell if hanging out with them has made this album, or my obsession with it, any clearer to me. But when chatting to Rex – whose character seems inherently warm but with a natural veil of irony covering every expression – I can picture what she’d be like in the late 70s, why her personality projected so well on record, why Vic approached her in the first place. After a while, our chat takes a detour, and I spend some time looking at pictures of Rex’s two really cute Maine Coon cats on her iPhone while Vic sighs good naturedly and downs his beer. We’re about to part ways before Rex says, “Hang on! I’ve got something for you!” and rifles through her bag, pulling out a small, crumpled white package with the words ‘Rexy II’ across. Inside is a CD. “We’ve been working on new music together, this is the first version of it,” she tells me. “You won’t like it! No one does! But we don’t care – have a listen anyway.” I thank them both and leave, wondering where the hell I’m going to find a contraption that still plays a CD.

A week or two later, I get someone in the office to lend me their external CD drive and listen to what Rexy have been making almost four decades after their only album. I don’t quite know what to expect, but it isn’t what comes out my headphones. The tracks are really, really weird. I love some of them. At one point, during a particularly chill lounge-y electronic song called “Benidorm Bye Bye” you can hear Rex shouting in the background “Did you just call me a slag?! I’m going to fucking do you!” In another, she sings about snorting a huge line and waiting for it to kick in, the keyboard spiralling and swirling around her. Some of it sounds like background music from The SIMs, but with a London accent talk-singing over it. I quickly shut my laptop. Maybe the world will be ready for this in another four decades; Rexy seem to exist on a different time frame entirely.

I don’t know what more to say about Rexy other than you should listen to them if you’re into music that sounds like aliens dropped it off in a basement during the early 80s. Sometimes records come along that define an era. You hear them filling up dancefloors at the time, or being played repeatedly on MTV2 or Top of the Pops or whatever pop culture vessel is around, then years later you hear them getting revitalised at nostalgic club nights, or spoken about on late night Channel 5 countdown programmes presented by Alex Zane while an old kids TV presenter says, “it was just mad!” Other times, records fall through the cracks and hardly anyone speaks about them at all, until years later, in near-empty hotel bars, while Vengaboys play in the background.

You can follow Daisy on Twitter.

More

From VICE

-

(Photo by Matthew Simmons/Getty Images) -

(Photo by Arturo Holmes/Getty Images for ABA) -

Lily Phillips/Instagram -

Screenshot: Bethesda Softworks