You probably know the type, or at least have come across it once or twice. Nervous, neurotic, arrogant, quarrelsome, highly intelligent, quick to anger, quick to blame, all underpinned by a belief that the world is out to get them.

This is the portrait that emerged of Valery Fabrikant, the former engineering professor at Montreal’s Concordia University who murdered four faculty members and injured a secretary in a crime that shocked the city and the country 25 years ago this summer. It’s an image that has endured for a quarter century mainly because of Fabrikant himself. He has been a persistent thorn in the side of the province’s judges, prison officials and parole boards, beginning with his quadruple murder trial.

Videos by VICE

Fabrikant became a household name on August 24, 1992, when he arrived at Concordia University’s Hall Building in downtown Montreal armed with three pistols and intent on murdering those he felt had wronged him. Within minutes, four professors—Michael Hogben, Jaan Saber, Phoivos Ziogas, and Matthew Douglass—would be dead, and a secretary wounded with a gunshot to the leg. None of them had anything remotely to do with Fabrikant’s long-festering problems with his departmental colleagues and academic superiors.

Unlike most mass shooters, Fabrikant survived. He was arrested and put on trial, where his once-tolerated eccentricities, including a penchant for aggressive behaviour, were laid out in full public view. They didn’t do him any favours: he came across as petty, vindictive, unrepentant, and vain. He was rude and hostile to witnesses, the judge—whom he called a “low little crook”—and even the psychiatrists who testified that he was sane enough to stand trial. He went through ten lawyers over the course of the legal proceedings and did his best to disrupt every minute of his trial by veering off into tangents. He would read reams of irrelevant information into the trial’s official record. He would badger witnesses to the point of tears; and he stood by his actions, declaring himself to be the true victim.

If anyone hoped that prison would be the last they heard of Valery Fabrikant, they were wrong. Over the years, he filed appeal after appeal from his cell at Archambault prison north of Montreal. He’s filed so many that he has been designated a vexatious litigant by the courts, meaning he isn’t allowed to file anything unless he has specific permission. And every time he has filed a court motion or managed to make his way back into the headlines, he reopens wounds that the university has worked very hard to heal. He was in the news as recently as last summer, when he was denied permission for temporary absence from prison in order to visit his family. According to a federal court judge, the then-76-year-old still poses a risk.

The Fabrikant shooting, also known as the Concordia Massacre, is a weird, sad story—one of human failings, academic and financial mismanagement, petty egos and turf wars. It also has a long tail, extending for more than a decade, when a tightly-wound, somewhat desperate 39-year-old Soviet emigre turned up at the office of T.S. (Tom) Sankar, the chair of Concordia’s mechanical engineering department, in late 1979 looking for work.

Fabrikant, a native of Minsk, Belorussia, claimed to have fled the Soviet Union as a dissident, and persuaded Sankar to hire him as a research assistant. His salary would be $7,000 a year.

Sankar did not bother to check his new hire’s credentials. If he had, he would have found that Fabrikant had to leave the USSR because he’d been dismissed from previous posts due to threatening and disruptive behaviour, according to an investigation by the Montreal Gazette after the shooting.

As Morris Wolfe writes in his 9,000-word, award-winning article for Saturday Night magazine, “Dr. Fabrikant’s Solution,” Fabrikant wasted little time manifesting traits others would later find alarming.

“It didn’t take long for it to become clear that Fabrikant looked out for himself with a fierce sense of his own importance,” he wrote. “When the Soviet Union was slow sending him a few thousand dollars he’d inherited from his father, he wrote External Affairs demanding that Canada suspend grain shipments to the U.S.S.R. until he received his money. It also became clear that Fabrikant had no wish to be a research assistant, helping his supervisor with his work. In fact, he was dismissive of Sankar’s research.”

As described by Wolfe, Sankar came across as the indulgent boss of an eccentric but brilliant protégé, willing to overlook his cantankerous, aggressive demeanour. There were reports about Fabrikant being unpleasant to work with, of outbursts in the university’s computer lab, of allegations of harassment from academics who turned him down for a job and of rudeness from editors of academic journals.

It would emerge later that Fabrikant had credited Sankar as co-author on over two dozen papers he published in the span of just four years—an amazing tally for anyone, even more so for the administrative head of a department. In the cash-strapped world of academia, having your name on published articles can lead to grants, advancement, and tenure.

Fabrikant’s rise through Concordia was swift and lucrative, according to Wolfe. He was promoted repeatedly, becoming research associate professor in 1983, despite continued complaints about his behaviour. By 1985, he was one of three faculty members appointed to a new research centre funded by the Quebec government, with the prospect of tenure—the elusive prize for the typically peripatetic academic—dangling alluringly after five years. The centre was headed by T.S. Sankar’s brother Sheshadri Sankar.

By 1988, however, Fabrikant’s position was less stable. T.S. Sankar had resigned as head of the mechanical engineering department over financial irregularities the previous year (though he remained on as a professor). Then Sheshadri Sankar told him that his position at the centre would not be renewed the following year. “Fabrikant was thunderstruck,” wrote Wolfe. “He had been at Concordia for eight years. He was 48 years old, had a young wife, two small children, and no job prospects.”

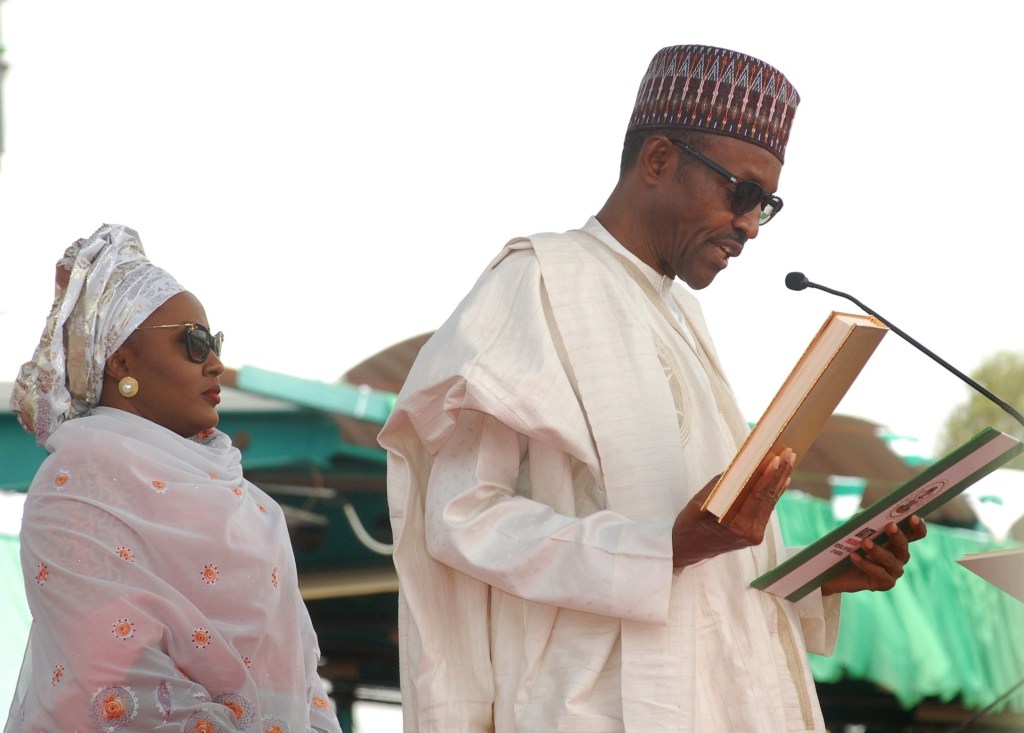

Jennifer Douglass sits at a granite table dedicated to her father, Matthew Douglass, a Concordia University professor who was murdered by colleague Valery Fabrikant on August 24, 1992 (CP PHOTO)

Fabrikant believed the reason for his impending termination was due to him having stopped co-crediting colleagues, including T.S. Sankar, on his papers. Meanwhile, reports of his belligerent behavior continued to accrue. He began taping conversations with colleagues, in which he would disparage Sankar. He got into petty arguments with university management over petty things like paying for a printer. This led him to threaten to go public with allegations about certain spending habits at the department and the extent of Sankar’s contributions to his published papers. Eventually, Sheshadri Sankar re-hired him with a two-year contract.

Fabrikant, as Wolfe writes, was now emboldened and using increasingly violent language. He spoke of shooting the Sankars and others, and taking Concordia’s then-rector Patrick Kenniff hostage.

That did not stop his department head for calling for his promotion and appointment to a tenure-track position in September 1990. But unbeknownst to Fabrikant and his boosters, Rose Sheinin, the relatively new vice-rector academic, had begun compiling a dossier of the professor’s increasingly erratic behaviour, which included threatening phone calls left on her answering machines both at work and at home.

Nevertheless, the department refused to abandon Fabrikant. Sheinin “had the impression his unpredictability spooked them,” wrote Wolfe. “And Sheinin’s poking her nose into the almost-all-male world of engineering irritated them. No woman, even if she was the vice-rector academic, was going to tell them what to do.” Give him what they wanted, they seemed to be telling her, and leave him alone.

So he was given another two-year contract, at $60,000 per year. And yet he still wasn’t happy, arguing with his administration over perceived limits to his academic freedom and research money.

By October 1991, the mechanical engineering department had had enough of Fabrikant and his incessant demands. They decided not to renew his contract, but were overruled by the university’s faculty personnel committee. Wolfe suggests that someone had tampered with Fabrikant’s personnel file to remove all documents that may have portrayed him in a negative light.

From then on, Fabrikant appears intent on burning down everything around him. Using the university’s email system, he began making allegations of persecution, financial and academic fraud and conflicts of interest against his former colleagues. An expert in workplace violence suggested to a university official that Fabrikant’s behaviour was a cause of real concern that needed to be taken seriously. That spring, amidst mainstream media coverage of Fabrikant’s complaints, a young woman came forward claiming Fabrikant had raped her in 1982. No charges were ever laid against him.

It was around then that Fabrikant completed a firearms course, obtained a firearm permit, and bought a pistol.

His behaviour became even more aggressive over the spring and summer of 1992. In April, he launched a lawsuit against his former department chair, T.S. Sankar, and the dean of the engineering and computer science faculties, Srikanta Swamy. Then there were allegations of grade inflation by his students, and he got into an argument with department chair Sam Osman over courses he was assigned to teach. In late June he demanded Osman’s secretary Elizabeth Horwood sign an application for a permit that would allow him to carry a firearm. She refused, and reported the incident.

That should have been enough for the university to end its relationship with Fabrikant—but it wasn’t. Rector Patrick Kenniff did not suspend him with pay, as vice-rector Sheinin and others recommended. He cited lack of evidence. Other internal squabbles ensued, often over money. There were talks about awarding Fabrikant early retirement with full pay, but negations collapsed when the then-52 year-old demanded first ten, then 13 years full salary.

By mid-August, Fabrikant had reached a breaking point. He was being cited for contempt of court in his lawsuit against Sankar and Swamy, and was due in court to face that charge on Tuesday, August 25. By the third week of the month, he was sending out mass emails threatening legal action against Concordia while hinting that his life was in danger. On Friday, August 21, he was told by Concordia’s lawyers he may lose his job.

That afternoon, his wife picked up two guns she’d ordered from a catalogue and took them home.

Fabrikant’s rampage began just after 2:30 PM on Monday, August 24. In a briefcase, he carried a five-round .38 Smith & Wesson revolver, a 6.35mm Meb semi-automatic pistol and 7.65mm Bersa, along with a significant amount of ammunition.

Emerging onto the ninth floor of the Hall Building at the university, Fabrikant initially went looking for Dean Swamy and department chair Osman. But, unable to find them, he went to his own office instead.

The first victim was Michael Hogben, the president of the Concordia University Faculty Association. He had arranged to give Fabrikant a letter barring him from the CUFA offices without prior permission. Fabrikant shot him three times. Hogben died on the scene.

When Hogben’s colleague Jaan Saber heard the commotion, he called out. Fabrikant walked over and shot him twice. He then shot Osman’s secretary, Elizabeth Horwood, injuring her in the thigh. Fabrikant then made his way through the building’s corridors until he encountered Phoivos Ziogas, the head of the electrical and computer-engineering department. He shot Ziogas twice and then grappled with another professor, losing one of his pistols. Making his way back to Osman’s office, he encountered civil engineering prof Matthew Douglass, who was a friend of Osman’s. Fabrikant shot him four times in the head, killing him almost instantly.

Fabrikant then took a professor and a security guard hostage, holding them for over an hour while he phoned 911 and demanded access to a TV reporter. Eventually, the professor and the guard were able to overpower Fabrikant while he was distracted, and police arrested him.

Saber died of his wounds the next day, Ziogas of his almost a month later. None of the victims had any bearing on Fabrikant or his grievances.

The immediate aftermath of the shooting was stunned confusion, grief and horror. Two weeks after the shooting, in the first issue of the new academic year, Concordia’s student newspaper The Link published an issue devoted almost exclusively to the shooting.

Hogben was described as “a peach who didn’t use his status as a professor to feel superior” and “a dedicated environmentalist.” Douglass, who’d joined the university when it was called Sir George William in 1966, as having “a great talent for negotiating and mediation. He never got angry or forced an argument.” He was due to retire the following year. A grad student said of Saber, who’d just turned 46, “When there was an idea he was enthusiastic about, you had to either jump on the train or get off the track.” He’d recently been given an award for outstanding contribution to student life.

Ziogas was still alive when the article was published, but he would die soon after.

In the same issue, vice-rector Sheinin wrote that the shooting “seriously damaged the soul of this university. I don’t think any of us will ever be the same again.”

And Charlene Nero, then the co-president of the Concordia Student Union, added, “Making this university into a fortress will not mend the fabric of this community nor will it make it a safe, comfortable place to work and learn. Nor will it undo the events of August 24.”

Sadly, Montreal even in 1992, wasn’t a stranger to school shootings. Three years prior, a frustrated 25 year old misogynist loner named Marc Lépine walked into the École Polytechnique, a prestigious engineering school attached to the Université de Montréal, with a semi-automatic rifle. Claiming in a suicide note that women ruined his life and railing against feminism, he murdered 14 women and injured 14 other people before shooting himself.

Nor would Fabrikant’s be the last school shooting here: On Sept. 13, 2006, Kimveer Gill murdered one student and wounded 19 others at Dawson College. He also wound up killing himself after being shot by police.

Fabrikant’s trial turned into a circus. He fired 10 lawyers, eventually deciding to represent himself in court. Over the course of six months, from March to August 1993, Fabrikant called 75 witnesses to the stand, where he would badger, berate and reduce them to tears. He read irrelevant information into the court record, sneered and mocked Justice Fraser Martin and insulted two psychiatrists who deemed him fit to stand trial. He was cited for contempt of court six times and referred to the trial as “the Muppet Show.” Eventually, Martin called an end to proceedings at the end of July. When the jury was finally allowed to deliberate, it took them all of seven hours to find him guilty of four counts of murder. At the sentencing, Martin said, “Today your credentials are firmly established as a vicious murderer, a wretched man, puffed up and transformed by the power of the gun into an artificial giant.”

The fallout did not end with Fabrikant’s trial. The massacre shook the university’s establishment. Two reports were commissioned, one by John Scott Cowan of the University of Ottawa, presented in May 1994, the other by former York University president Howard Arthurs, released in April 1994.

Both reports describe serious shortcomings at the university and recommended substantive changes to how the university handled matters academic, disciplinary and financial, as well as security procedures. Vice-rector Sheinin and Rector Kenniff were eventually replaced, and Swamy and the Sankars left the university.

Fabrikant remains little more than a bad memory for most people at Concordia, and a pain in the ass for the Canadian penal and justice systems. Even though he was designated a vexatious litigant in 2000 due to his multiple court motions filed from his prison cell, Fabrikant still managed to get before a judge a handful of times in recent years, usually unsuccessfully.

A bid for a hearing for early parole was turned down in 2008. The presiding judge said, “The dangerousness of the petitioner in the controlled environment of a penitentiary cannot be compared were he to be liberated. The death of four people is testimony to how the petitioner resolves conflicts when in society. Equally worrisome is that the groups of people he has entered into conflict with over the last 15 years has expanded. It is no longer limited to work colleagues but now includes correctional officials, doctors and justice system participants.”

He has been denied access to a computer, and his 2015 bid for temporary release to visit his family was also denied. His one victory came in 2014, when he was granted a second winter parka.

Today, Concordia is trying very hard to keep Fabrikant’s memory buried. Other than four granite tables in the lobby of the Hall building, there is little to remind today’s crop of students—most of whom hadn’t been born when he went on his shooting spree—of that day 25 years ago. As of yet there are no plans by the university to mark the anniversary of the shooting.

Fabrikant is eligible for parole this year. Now 77, he complains about his health and age-related infirmities, going to far as to sue the government (successfully) for an extra winter parka in 2014.

But he is still apparently dangerous enough for a federal judge to turn down his his application for temporary prison absences last year. She ruled that the parole board’s conclusion that he represented “an undue risk to society” was supported by evidence and there was no reason to overturn it.

Follow Patrick Lejtenyi on Twitter.