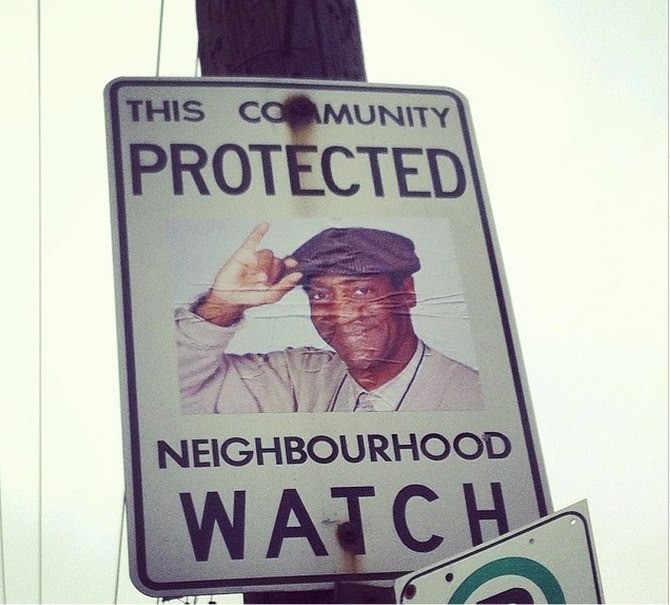

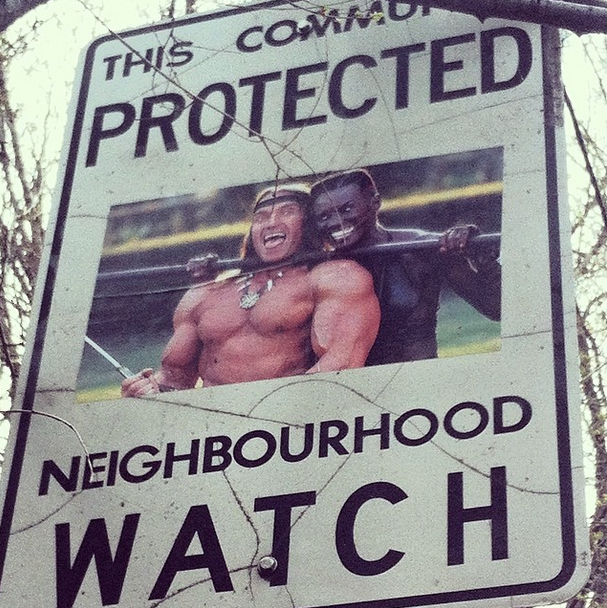

Andrew Lamb is a Canadian artist who, over the last two years, has been on a mission to rejigger neighborhood watch signs around Toronto to feature 1980s and 90s icons from morning cartoons, cult shows, and comic books. So far, he’s amended more than 70 signs, and thanks to his efforts my neighborhood is now presided over by Mulder and Scully and I’ve never felt safer. The 30-year-old artist makes his living creating puppets and has been working for the past few years on the technology required for a big planned project involving covertly painting Toronto bike lanes.

We caught up with him to chat about this project, public art, and whether or not this entire thing is technically illegal.

Videos by VICE

VICE: When did the project start?

Andrew Lamb: It started in the summer of 2012, after I noticed that the red graphic used on old neighborhood watch signs fades away after years of sun exposure—but the black lettering stays perfectly sharp. So there are all these signs that have become little blank canvases framed with a title, but there is no content. So I started wheat-pasting images of fictional superheroes, crime fighters, and do-gooders from my childhood on them.

How many signs do you have up now? Is it exclusive to Toronto?

As of now, there are 61 unique signs, five duplicates, and two that are kind of non-canon to the project.

What do you mean by non-canon signs?

The “non-canon” signs have a graphic that are close to the original icons, except the houses are hot rods and look like Ed Roth characters with their tongues hanging out. Not really superheroes or crime fighters.

Do you have a favorite one?

I’m a big fan of Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley from Alien, and the Leslie Nielsen/Lt. Frank Drebin character from Naked Gun is a favorite too. Screwball comedies were big in my house when I was a kid.

Is this technically illegal? Have you gotten in trouble at all?

I think it may fall under postering. Someone started yelling at me when I was putting up an image of Judge Dredd that I was in violation of the Highway Traffic Act. I wanted to yell back, “I AM THE HIGHWAY TRAFFIC ACT,” but I thought it would have been lost on them.

What is the project about, for you? Does it mean anything, or does it just rule? Where did the idea come from?

I like the concept of a public fountain of youth as municipal infrastructure, something that invokes nostalgic memories, like it’s the city’s business to make you happy.

What have your past projects been like? How does this current one relate?

I have made a couple “public zen” gardens when the city occasionally pulls up sidewalk stones. Sometimes, there is some nice sand under there. I pick out the cigarette butts, find some nice rocks, and put a rake nearby so passersby can make patterns in the sand. The same summer I found a large mound of poured concrete, which I painted to look like a breast. I suppose I am just pushing things that are already halfway done.

What appeals to you about working with the city’s existing infrastructure to create art?

Working with city infrastructure is a way to take something that can be perceived as cold and formidable, and bring it to a more personal level, taking something structured and making it into something whimsical. The appeal to me is making people happy.

Follow Monica Heisey on Twitter.

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb

Andrew Lamb