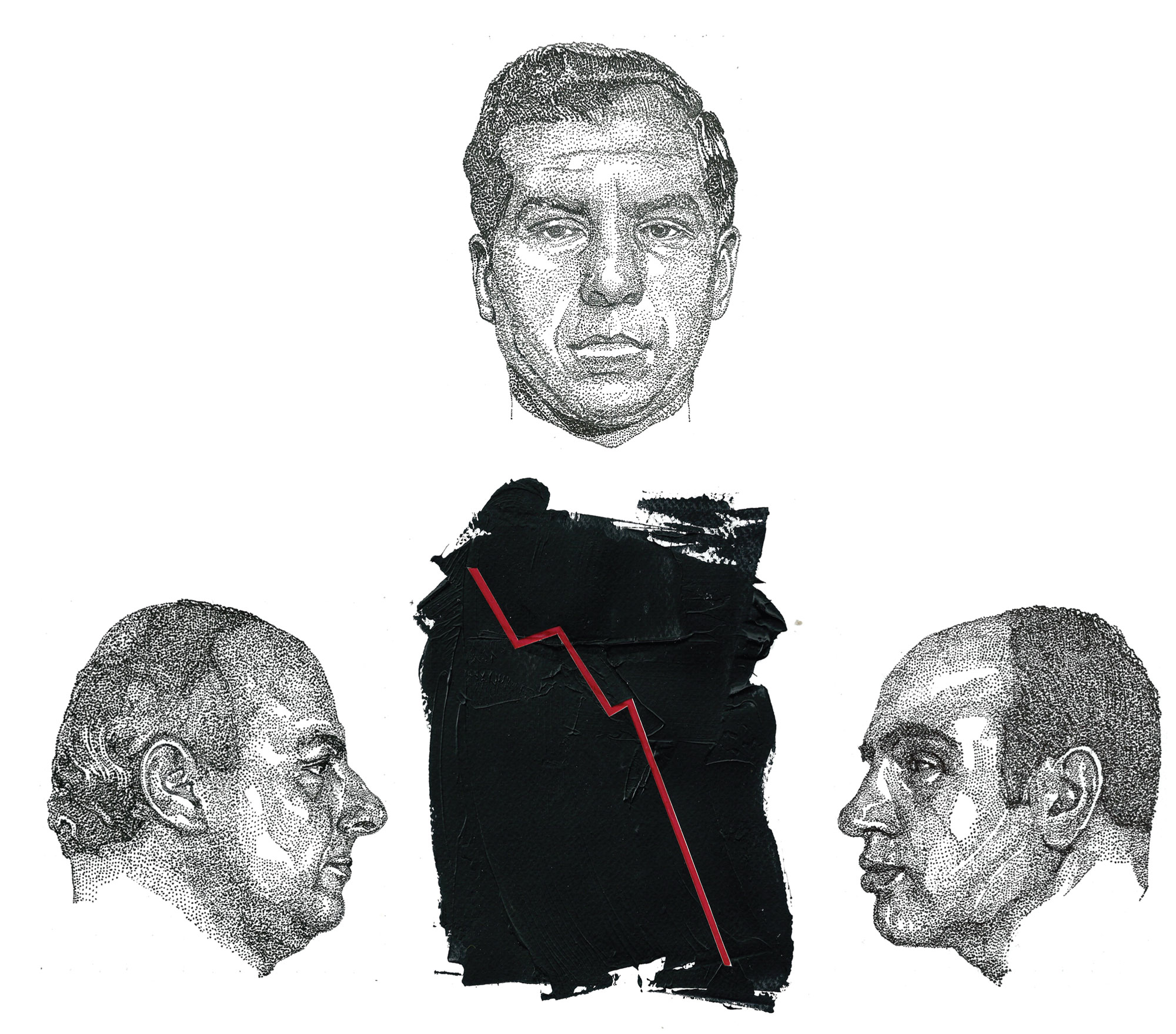

Clockwise from top: New York gangster Lucky Luciano, Chicago bootlegger Al Capone, and Camorra drug lord Paolo Di Lauro, who made a killing off of economic crises. Illustration by Jacob Everett

The Mafia has always profited from economic crisis. Recessions fill up the mob’s coffers and boost its social standing.

In fact crime is one of the few sectors of the economy that thrive in moments of financial decline. Just look at the past decade, when the United States suffered a collapse in its housing market, Italy risked default, and Greece, Spain, and Portugal came to the brink of bankruptcy. During all that time, drug trafficking reached unprecedented heights of prosperity.

Videos by VICE

It’s always been this way. In the Great Depression, the Italian-American mob, which was already reaping the benefits of Prohibition, saw its business grow even more. The consumption of alcohol and drugs increased as uncertainty about the future caused people to seek refuge in them, the penniless and destitute turned more often to loan sharks, and general hopelessness about the future spurred the rise of Mafia-organized gambling, sports betting, and illegal lotteries.

And it doesn’t end there. The Mafia exploits these moments of uncertainty to validate its organizations and to build consensus in society. After the stock market crashed in 1929, Al Capone decided to mobilize his restaurant and garment businesses to feed and clothe Chicago’s poor. (In the 1980s, Pablo Escobar would reprise this demagoguery when he offered to pay Colombia’s public debt out of his own pocket.)

While politicians and the press worried about how to end the Depression, the Italian-American bosses gloated in the situation, using it as an opportunity to reorganize and relaunch their illicit enterprises. It was during that period, for example, that the Chicago Outfit was consolidated. It was at the end of the 20s that Lucky Luciano came to understand the importance of the heroin trade. And it was in 1931 that gambling was legalized in Nevada and the bosses conquered Las Vegas.

Only in the early 1930s, when America had caught a glimpse of the way out of the crisis, did US institutions begin to truly concentrate on the fight against the Mafia. At that point the first arrests were made: Luciano and Al Capone ended up in jail, but they had established themselves so well during the recession that they successfully managed all of their ventures from prison. And the bosses of the Italian-American Mafia had such power that American intelligence asked their help with security during World War II in exchange for lessened sentences and impunity.

Though history teaches us that in times of crisis it’s necessary to raise our guard against gangsters and racketeers, institutions tend to lower their defenses, handing a carte blanche to organized crime. So it continues today.

In December 2009 Antonio Maria Costa, then the executive director of the UN Office on Drugs, made a shocking declaration: He revealed that the earnings of criminal organizations made up the sole liquid assets at the disposal of some banks seeking to avoid collapse during the 2008 financial crisis.

But how did we get to this point? According to the International Monetary Fund, between 2007 and 2009, banks in the United States and Europe lost more than $1 trillion in toxic assets and bad loans. Many big credit institutions failed or were put under temporary receiverships, and by the second half of 2008, cash flow had become a major problem for the banking system. Due to the banks’ reluctance to grant loans, the system was practically paralyzed, and criminal organizations seemed to have huge quantities of cash to invest—that is, to launder.

A recent investigation by two Colombian economists at the University of Bogotá, Alejandro Gaviria and Daniel Mejía, revealed that 97.4 percent of Colombia’s drug-trafficking revenue is regularly laundered in American and European banking circuits through various financial operations. We’re talking about hundreds of billions of dollars. The laundering takes place by way of a system of blocks of shares that work like Chinese boxes or Russian dolls: The cash is transformed into electronic titles, passed from one country to another, and when it arrives on another continent it is nearly untraceable. That’s how interbank loans came to be systematically financed with money from drug trafficking and other illicit activities. Some banks relied on this money to save themselves. Consequently, a large part of the $352 billion originating from drug trafficking was absorbed into the legal economic system, perfectly cleaned.

On October 26, 2001, in the wake of 9/11, President George W. Bush signed the Patriot Act with the goal of preventing, identifying, and prosecuting international money laundering and financing of terrorism. This law established that the US Department of the Treasury can ask national financial institutions to undertake a series of special measures with regard to jurisdictions, institutes, or foreign bank accounts suspected of being involved in money laundering.

But despite the tough measures taken by the American government, the financial crisis that started in 2008 even caused American banks to turn a blind eye to illicit activity and to find a way around the law. In February 2012, before a congressional hearing on organized crime, Jennifer Shasky Calvery, chief of the Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section of the Department of Justice at the time, declared: “Disguised in the trillions of dollars that is transferred between banks each day, banks in the US are used to funnel massive amounts of illicit funds,” confirming, in a sense, that the Patriot Act was not enough to distance the flow of dirty money from the American economy and finances.

The tie between drug trafficking and banks is not new. As Costa declared to the Observer, “The connection between organized crime and financial institutions started in the late 1970s, early 1980s, when the Mafia became globalized.” Until that connection was made, criminal organizations’ money had circulated primarily in cash. With the globalization of the Mafia, it became easier and more convenient to transfer money electronically from one part of the world to the other through the use of electronic titles and virtual cash. But according to the Observer, at the end of the 80s the authorities increased their oversight of laundered money in banks, and criminal organizations began to operate in cash once again.

Yet the anti-money-laundering authorities hadn’t accounted for the financial crises that spread across the globe in the early 2000s, causing a shortage of liquid assets from Russia to the United States. This shortage not only would bring the banks to their knees but also would open them up to the enormous assets of criminal organizations. And the cases in the news involving some of the biggest global banks in recent years demonstrate this fact.

According to some experts, the banking powerhouses of London and New York have become the two biggest laundries of dirty money in the world. This title no longer belongs to tax havens like the Cayman Islands and the Isle of Man but to Lombard Street and Wall Street.

Translated from the Italian by Kim Ziegler