The Bauhaus, the German art school that turns 100 this year, is best known for its minimal unadorned designs that combine clean curves and geometry and for its embrace of the technical and the commercial. (See the Barcelona chair by Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich; or the sleep MT8 lamp by William Wagenfeld and Carl Jakob Jucker.) It was the quintessential movement of rational modernism, in direct opposition to Dada and Surrealism, which also happened around the same time, respectively, in Switzerland and in France.

But beneath its utilization and rigorous veneer, the Bauhaus was a fertile ground for the artistic expression of what were historically marginalized identities, namely women and queer people, who made art expressing a range of ideas that seem at odds with the paradigm of rationality their institution was known for. A subject that Elizabeth Otto, a scholar specialized in the marginalized aspects of the Bauhaus institution, explores at large in her new book, Haunted Bauhaus: Occult Spirituality, Gender Fluidity, Queer Identities, and Radical Politics.

Videos by VICE

In a way, it was inevitable. The 1920s zeitgeist had seeped into the Bauhaus: the figure of the Neue Frau, “New Woman” embodied an idea of modern femininity that thrived during the interwar period. This “New Woman” lived in metropolitan areas, and was stereotypically associated with fast fashion, fearlessness and ruthlessness. The year 1919 also saw the establishment of Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexual Science in Berlin, which had its team of scientists and researchers posit that a spectrum of sexual identities and preferences and behaviors was natural to humanity pre-dating the mission of the Kinsey Institute by almost 30 years: the institute coined the term transsexualism (now an obsolete term, transgender being preferable), and pioneered gender-reassignment (now affirmation) surgeries. The aim was to educate people on sexuality, sexual health, contraception, and to facilitate women’s emancipation.

Bauhaus artists enjoyed analyzing, dissecting, or subverting, the Neue Frau stereotype and, when it comes to queer artists, their queerness is seamlessly integrated in their works. Curiously, these more “subversive” and experimental works mostly came in the form of photography, which Bauhaus artists practiced alongside other art forms.

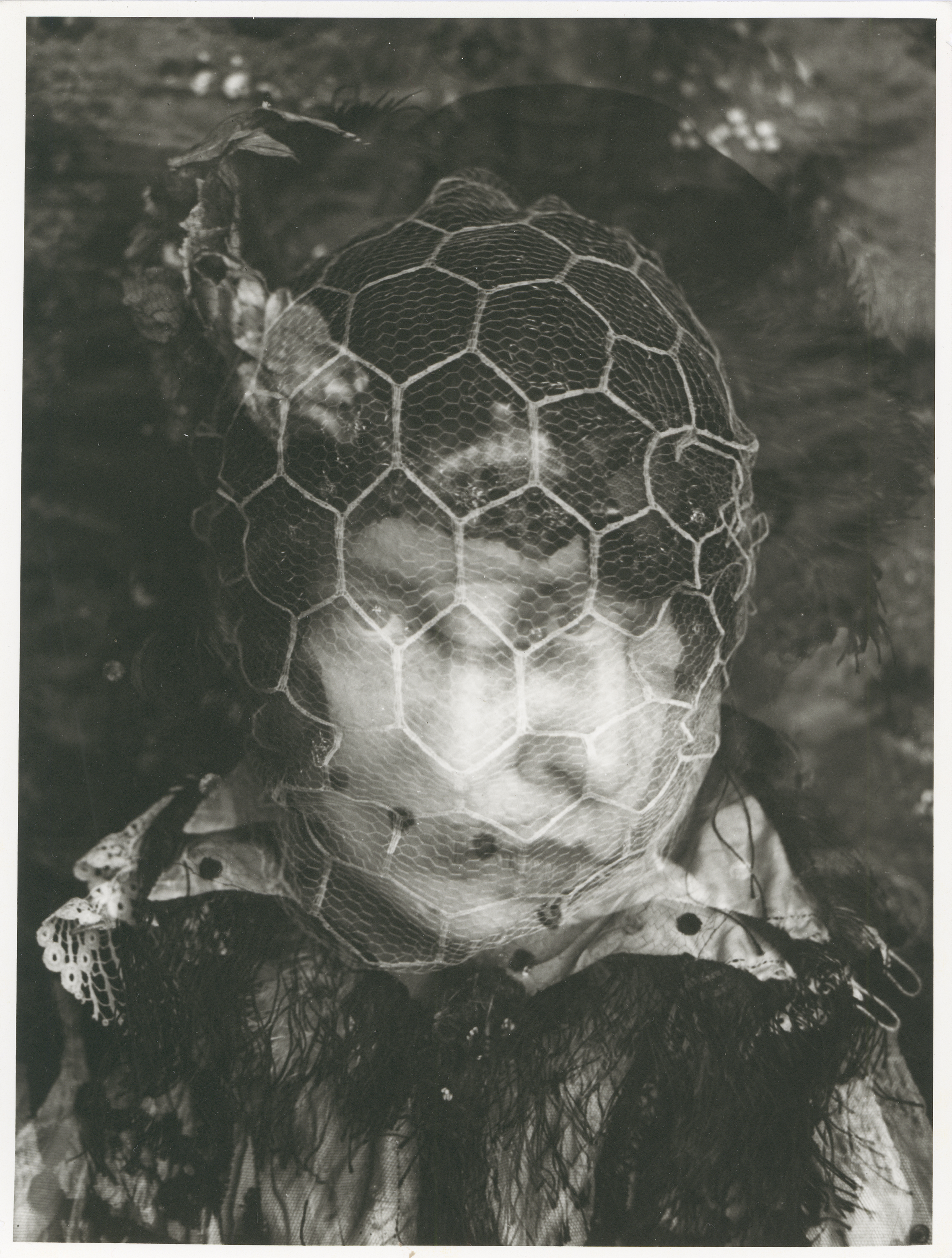

Gertrud Arndt was considered the best weaver among the Bauhäuslers for her work as a colorist and also for her rug-making (one of her creations was in Walter Gropius’ office from 1924) but her subversive creativity emerged in her highly theatrical, almost campy portrait photography, which she took up out of boredom after giving up weaving. One of her main muses was fellow weaver Otti Berger, who owned a trunk full of costumes and fabrics. The result of this collaboration is a series of portraits of Berger, where, in stark opposition to the Neue Frau aesthetic, she interprets various characters, such as a clown, or a Spanish lady. Arndt’s other muse was herself. The series called “Mask Photos” consists of a series of self-portraits where Arndt adorns herself in heavy makeup, costumes, and veils, interpreting, in a camp fashion, feminine tropes such as the widow, the socialite, and the little girl. “It struck me how, in those photographs she was almost smothering herself in fabric, the material she renounced,” says Otto. She wears no masks to speak of, but uses her face and body as a canvas for outlandish outfits, heavy makeup, and distorted facial expressions. Through these photos, argues Otto, Arndt removes herself from the future-and-efficiency-oriented philosophy of the Bauhaus, existing instead in a present that is “blasé and ornamental.”

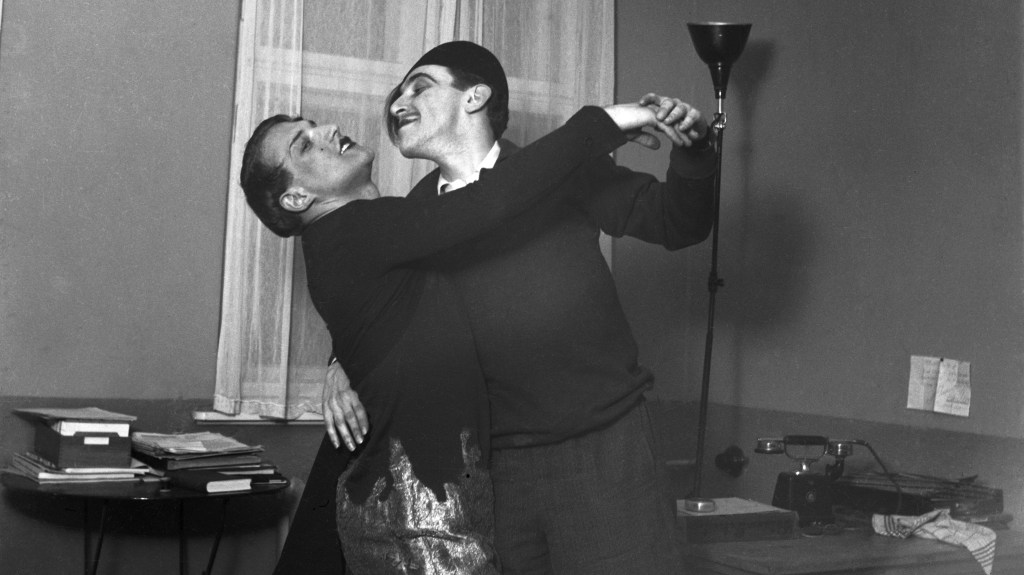

Max Pfeiffer Watenphul was perhaps the most notable exponent of the queer Bauhaus, as he combined Bauhaus aesthetic with “campy” imagery of gay and lesbian subcultures. Although he is mostly known as a painter who specialized in still-life subjects and had a fascination for the Mediterranean; in his photography, he embraced a grotesque aesthetic that was far from the predominant New Objectivity of the decade. “Made brilliant new photos. But people say they’re very perverted!!!?” he wrote in a letter to his friend Maria Cyrenius. “Woman with a Fan” sees a hyper-feminized subject smiling coyly played by a man in drag adorned in flowers, pearl and feathers. This piece ended up in the collection of Nazi industrialist Kurt Kirchbach.

American-born Florence Henri, originally a concert pianist, who discovered photography as a primary medium when she visited and enrolled in the Bauhaus in 1927, took up female-centric photography that encompassed queerness and erotica. A 1928 portrait of her partner Margarete Schall, for instance, sees her reflected in a mirror, sporting what we can call a “boyish charm”: she wears modest, masculine clothes, has a close-cropped haircut and, holding a cigarette, appears lost in thought. “This is a remarkably self-possessed woman, a lesbian subject whom we can see but can’t quite place, for she is just out of reach,” writes Otto in Haunted Bauhaus. Her erotic photography combined the ideal of neue Frau with elements of bondage and fetishism. One of them portrays the famed fashion designer, photographer and essayist Ré Soupault, posing with her eyes closed, reclining on a soft white ground, nude but for a a piece of netting draped over her body. Another one, dated 1934, sees a lithe woman in the nude, her waist accentuated by a belt, as if she were dressed up for an erotic game; her gaze appears downcast, but not in a submissive way. Henri’s female models were both sensual and self-possessed: they hardly sported coy, or come-hither looks. Rather, their gaze is averted from the viewer, which suggests they’re in their own thoughts.

None of this was advertised too overtly, though. “The institution didn’t make any overt space available for gender experimentation in terms of representation,” explains Otto. “The institution signaled very broadly that it was a place of experimentation and new life, so I think to young queer people that was a dream, because they knew they were looking for something else.”

![r.bliss x MOM publishing: "LOVE" [supplied]](https://www.vice.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/05/1717114913901-screenshot-2024-05-07-at-21037-pm-scaled.jpeg?w=1024)