This article originally appeared on VICE Indonesia.

This article is part of a wider initiative by VICE looking at the state of the environment around the globe. In Asia-Pacific, each VICE office is examining the main concerns from their territory, in an effort to gauge the health of the planet as a whole and to highlight the widespread need for change. For other stories in this series, please check out Environmental Extremes .

Videos by VICE

A trench enclosed a piece of land filled with weeds and shrubbery as far as the eye could see in the Indonesian village of Air Hitam Laut, Jambi. Two men approached the area and scouted the scene. Landowner Safarudin hired Erwin (both only go by one name) to prepare four hectares of his land so it could be farmed with betel nuts. That day, the plan was to clear the trench of the thick shrubbery that had covered it over the summer, using a technique known locally as merun, a traditional method of selective land-clearing through the use of fire.

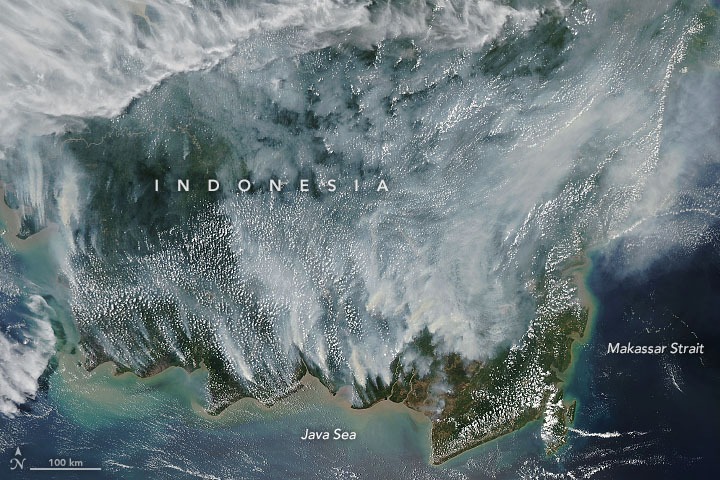

The job was simple: All Erwin needed to do was light a match against some dried grass and let the flames do the rest. This widespread practice contributed collectively to the fires currently consuming the provinces of Kalimantan, Sumatra, and Jambi, as well as the haze engulfing multiple neighbouring countries.

“[At the time] we wanted to plant betel nuts,” Erwin told VICE. Using merun to clear land is much simpler than uprooting all the weeds and shrubbery by hand, and allows seeds to be quickly planted. It also helps farmers locate depressions in the land. “Our intention was to clear a path, but the fire spread everywhere,” Erwin said.

VICE met with Erwin and Safarudin in their cell at the West Muara Sabak Police Station in Jambi, a province in Western Indonesia. Their intention to clear the trench ended in disaster. The fire consumed not only the land surrounding the trench, but also other vegetation beyond Safarudin’s 4-hectare piece of land. The fire raged toward Air Hitam Laut on Aug. 10. Fifteen days later, police arrested the two accomplices.

From the onset, Safarudin was well aware that his actions might land him 12 years in jail. “I knew it was against the law,” he said. But for farmers with limited budgets, paying someone to clear land manually isn’t in the books. “Hiring people to do it manually costs Rp2 million (US$142) per hectare.”

Many farmers and groundskeepers across Jambi, Riau, and Kalimantan face the same problem. Using fire to clear land is affordable and many of the suspects are well aware of the environmental damage they’re causing.

On Sept. 9, Jambi Metro Police arrested a government worker who scorched 2,500 square meters of his co-worker’s land. “He did it on purpose by piling up trash and burning it so that he could cultivate coffee beans,” said Mardiono, head of Jambi Metro Police who goes by one name.

Merun is meant to spark small fires that cover 1 hectare at most. Anton, a Jambi local who goes by one name, said that the technique’s bad reputation is unfair. When done correctly, the fire used to clear land should not spread beyond the intended area, especially not into the jungle. Anton said that locals know tricks to efficiently burn land for farm use.

“This method was passed down from our ancestors,” he told VICE. It’s impossible to tackle hectares upon hectares of land without burning it, he said. “If we’re not allowed to use fire, then we should be provided with the proper tools, like excavators.”

Safarudin said he feels no remorse and that he was certain he would be caught some day. “I’m old and they’ve only just caught me,” the 56 year-old said.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo (Jokowi), who visited Riau on Sept. 17 following backlash on social media, has since ordered officials to crack down on the individuals and corporations responsible for the crisis. This year’s man-made disaster is nearing the scale of Indonesia’s 2015 fires, which consumed 2.6 million hectares of land, caused US$15.7 billion in damages, and are considered the worst in Indonesia’s history. Jokowi also said police and military units that fail to arrest suspects would be dismissed.

Shortly thereafter, police announced that 230 individuals had been identified as suspects behind the fires. A similar or larger number of suspects is projected to come out of Sumatra once all the data is compiled.

The haze plaguing areas in Indonesia—plus regions in Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand—are difficult to pin on individuals. Safarudin and Erwin are guilty, and they admit it. But more of them are out there and their identities are unknown. Many of them start fires for big corporations. Time and time again, Indonesian officials are hunting down low-level accomplices instead of the big players. At the time of writing, the Indonesian government has only identified five companies allegedly responsible for setting fire to land, while 42 other companies have had their land quarantined.

This is just one of many cases in which the actions of a few affect the lives of many innocent people, including Safi’i, a Jambi local who goes by one name. He remembers how in October 2015, he began to feel feverish as his home became enveloped in smoke. With his wife in tears, he and his family waited for a call from the police.

The 62-year-old had been fishing in a pond just outside a palm oil plantation, when he saw smoke begin to rise. Although he had been near the fire, he said he had nothing to do with it. “I wasn’t even smoking. I had no lighter on me,” he said.

Safi’i sought the help of the Jambi chapter of the Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi), asking them to accompany him to the police station. After rigorous interrogation by officers, police finally released him. “I couldn’t sleep that night,” he told VICE.

Ponidi, another Jambi resident who goes by one name, is currently being held in a cell at a Jambi police station for involvement in fires surrounding a palm oil plantation, but he swears it wasn’t his fault. The land in question had been torched a day before the police showed up at his house to arrest him.

In the village of Sipin Teluk Duren, the blackened earth released a steady flow of smoke, even though the area had been sprayed with water by a government fire department and the company operating the land. When the gas powering their water pump wore thin, the team had to stop their efforts to extinguish the flames. The bushy area was quickly reignited less than 15 minutes later.

Another factor that triggers Indonesia’s yearly forest fires is the El Niño phenomenon, which is believed to have made land in the six affected provinces more susceptible to fires. But environmentalists believe the more pressing issue is the government’s failure to enforce the law, resulting in yearly forest fires and transboundary haze.

“Long summers and the El Niño create difficult circumstances, but it’s the government’s job to respond accordingly. Because now, we have corporations independently causing these ‘fires’ because they want to clear land quickly and easily so they can plant trees for palm oil,” Kiki Taufik, Greenpeace’s Forest Campaign Manager for Southeast Asia, told VICE.

The Indonesian Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK) supports this claim, saying that 90 percent of this year’s forest fires are directly caused by humans.

Forest fires worsen deforestation that is already occurring because the recently scorched land is immediately used for industrial farming. According to data from Forest Watch Indonesia (FWI), only 11.4 million hectares of jungle remain in Sumatra. FWI said the constant deforestation in Sumatra is mainly due to the repurposing of land for industrial farming and mining.

Gafur, a Jambi resident who goes by one name, has seen his fair share of forest fires. Four years ago, the smoke caused his child to suffer from a respiratory illness. Despite this, he admits that the practice of clearing land with fire is somewhat traditional in the area, and that local farmers aren’t to blame. “It’s no secret that the effects of this type of land-clearing are not so much the fault of locals as it is the fault of corporations,” he told VICE.

Now, he’s demanding local and national authorities to completely ban the use of fire for land-clearing. “Even though it’s been traditionally done for years, the impact is extremely negative,” Gafur said. “Perpetrators should receive the highest form of punishment, including the seizure of their land.”

In 2015, the national government lost a citizens’ lawsuit filed by a group of activists from Kalimantan at the Supreme Court over government negligence during the 2015 forest fires. The court found Jokowi and a number of other public officials guilty of allowing the fires to continue unabated.

The president and relevant officials never produced any concrete policies in anticipation of the subsequent forest fires. Jokowi admitted that preventative measures at the national and regional levels failed to adequately mobilise.

“We don’t need to hold the same meeting every year. We automatically know that we must be prepared every dry season. We’ve been neglectful and allowed the fires to spread,” Jokowi said on Sept. 17 at a cabinet meeting during his visit to Riau.

The corporations that allowed their land to spread to other areas never truly faced any consequences. The government sanctioned them only by revoking their licenses to conduct environmental impact studies. The KLHK also shockingly refused to release the list of companies involved, while the government restricted public access to the list of implicated landowners operating their farmland under commercial licenses.

According to Greenpeace, nine companies have been declared guilty at the national level for the 2015 forest fires and must each pay a fine of Rp18,9 trillion (US$ 1.35 billion). It’s 2019 now, and none of them have had their land seized or their operating licenses revoked.

Ilsa Dewita, a mother of three, hoped that the government’s “crackdown” on the haze crisis would be more than just rhetorical. “Someone should be responsible for this,” she said. “I really hoped this hazardous smoke from a few years ago would be the last.”

Elisabeth Glory Victory contributed to this report.