This article appears in VICE Magazine’s Borders Issue. The edition is a global exploration of both physical and invisible borders and examines who is affected by these lines and why we’ve imbued them with so much power. Click HERE to subscribe to the print edition.

Anote Tong pointed his camera phone out to face an eroding shoreline at sunrise. “You can look out into the beautiful sea,” he said, before turning the camera back closely to his freckled face. “Beautiful, but on the way to be taken.”

Videos by VICE

Starting in 2003, when he was elected president of the island nation of Kiribati, a series of alarming reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change landed on Tong’s desk. By 2007, they laid out how a slew of climate change–related issues, from coastal erosion to groundwater shortages to increasing dengue fever, could soon force the nation’s 117,000 residents to join the 25 million people displaced by environmental impacts related to climate change every year. “I must admit there was a great deal of denial in the process. My initial reaction was anger, frustration, and a sense of paralysis,” Tong said.

The problem for the people of Kiribati (pronounced KEE-ree-bas), he said, was that they wouldn’t have anywhere to go. The reports detailed how climate change threatened to literally erase Kiribati’s borders. Sea-level rise meant that within this century, the South Pacific could swallow the 33 islands that make up the nation. Tong would have to develop what he called “radical solutions” to protect the people of Kiribati—building floating islands and underwater cities, and purchasing land from other sovereign nations. “If we are going to have to relocate,” said Tong, “we need somewhere to relocate.”

The science is clear: People who live in coastal cities, like Miami, Sydney, and Shanghai, are already vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Many will have to move internally within the next 80 years to get themselves out of harm’s way, with or without the help of their governments and aid agencies. For citizens of low-lying atolls like those that make up Kiribati, it’s a different story. Climate change isn’t just destroying people’s homes but their homelands, and there soon might not be any nation within which to move internally. Countries in the Pacific with little elevation above the ocean, including Tuvalu and most of the Marshall Islands, all risk becoming uninhabitable for their people by 2030.

This is the reality for almost 200,000 people of the South Pacific: Their countries might be wiped off the map, and literally no one can agree on what’s to be done about it and them.

In the past, wars and political conflict have changed states’ borders and shaped power over territories and people. But never before in the history of the world have countries lost sovereign territory permanently because of climate change. Though the question of what happens to the people and territory of states that sink into the ocean has been under discussion since at least the early 90s, there is still no international legal consensus on what can be done for these soon-to-be-stateless people. That has left it up to individual leaders and innovators like Tong to propose radical, sometimes imagination-straining solutions for how to maintain national integrity even when there’s no land on which the nation can stand.

As he faced the prospect of his nation literally sinking into the ocean, one extreme solution Tong considered while still in office involved moving the country underwater preemptively. Really.

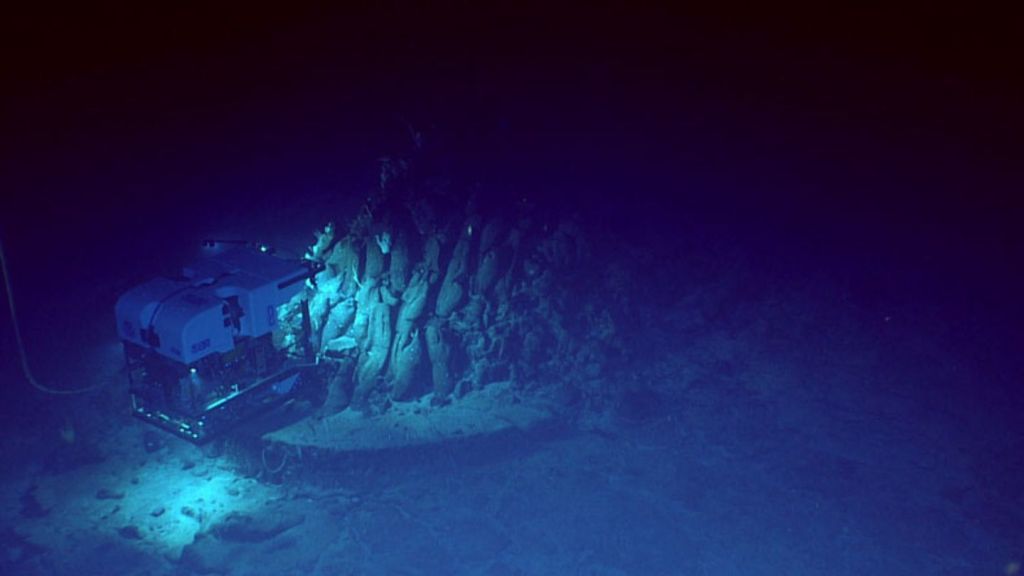

In 2014, the Japanese engineering corporation Shimizu unveiled a design for an underwater glass city called Ocean Spiral that could house as many as 5,000 people. The conceptual metropolis would consist of a spherical city, within which a tower would accommodate homes and work spaces. There would also be a spiral structure connecting this sphere with a base station on the ocean floor, 2.5 miles down—providing the city with essential resources such as energy, freshwater, and food. According to the Shimizu spokesperson Hideo Imamura, however, Ocean Spiral’s technology is still in development.

Since 2008, Shimizu has been working on another project, also noticed by Tong, known as Green Float, which Shimizu promised could be a solution to accommodate people from nations at risk of becoming stateless. The new floating city project would house 10 times as many people as Ocean Spiral and would be designed to withstand natural disasters such as typhoons and tsunamis. An agglomeration of floating islands, each less than two miles wide, forming a lily pad–like colony, Green Float would feature a 300-story-tall “city in the sky” tower. A section built on the outer edge of the central lily pad would host a beach resort and an ocean forest with a wealth of sea life nearby. Shimizu hopes to finalize a first unit, called Green Float II, by 2030, according to the French newspaper Le Monde. Technological innovations in the coming years could make the project possible through the ability to produce very light metal alloys right at an island’s building site, using magnesium extracted from seawater.

And yet, creating permanent floating homes at sea is not an isolated case: It’s been hyped by the Seasteading Institute, which advocates for “seasteads”—politically autonomous human settlements in international waters. According to Duncan Currie, an environmental lawyer and adviser to the High Seas Alliance—a partnership of organizations aimed at conserving the portions of the world’s oceans that exist outside any government jurisdiction—while rising seas may wreak havoc with maritime boundaries, territorially speaking, “the high seas belong to no one for being beyond national jurisdiction, so when it comes to exploitation, they belong to everyone.” Essentially, building floating nation-states in international waters appears to be legally feasible. It’s a reminder that even Kevin Costner’s Waterworld movie scenario is currently a possibility.

Up to this point, seasteading has mostly been the interest of a libertarian movement of freedom seekers gearing up to live in permanent dwellings at sea safe from government meddling. But Currie explained that with more than 50 percent of the ocean outside sovereign jurisdiction, it is also an avenue that may be increasingly explored for displaced populations. “The idea is not to get territory but to establish human habitation, and I think some island states are considering it as a solution,” he said. However, without a new ocean treaty, the legality is still disputed, and things are not quite working out for the lodgers of a two-story octagonal seastead floating off the coast of Thailand who will face the death penalty if they are convicted of violating that country’s sovereignty.

Let’s face it, floatable houses or underwater cities are not yet able to provide any long-term solutions for what Alex Randall calls a “humanitarian crisis” in the Pacific. According to Randall, who runs the Climate and Migration Coalition, a network of refugee and migration NGOs, the fact that nobody knows what happens to people from countries that will potentially get wiped off the map in a matter of decades is deeply frustrating: “The way I look at it is it’s also a really tragic answer, because there are clearly potentially millions of people who will be in that position.”

As Randall suggested, this is not just a crisis affecting a few dots of land scattered across a vast ocean—it is the future of 800 million people living in hundreds of low-lying coastal cities the world over. In several Pacific countries, villages have already disappeared. Tong recalled the thriving village where he went to school that no longer exists: “The community has totally relocated. We have a number of those in process. It’s real.” And yet what seemed to worry him equally is the conditions within which his people are forced to relocate. “I’ve always rejected the notion of our people becoming refugees,” he said. “That’s why I started advocating for a policy of migration with dignity.”

Part of that migration with dignity initiative involved the 2014 government purchase of nearly 6,000 acres of land in Fiji—another island nation, more than 1,300 miles away—to move Kiribati’s residents to. He wanted to develop a well-planned relocation program so that if and when people decided to emigrate, they could do so as people with skills and qualifications, not as “second-class citizens.” Still, today, the land remains largely uninhabited, and there doesn’t appear to be much political appetite for the move, either in Fiji or in Kiribati. In 2016, Tong was replaced as president by Taneti Mamau, who is known for downplaying the climate crisis and who has halted the migration with dignity project.

According to Alan Toth, a journalist who visited the purchased land in 2017, the government of Kiribati had given Fijian farmers permission to cultivate taro and coconut on the plots in the absence of Kirabti’s citizens. Claire Anterea, a former nun and the cofounder of the Kiribati Climate Action Network, said almost no one has moved there, and the purchase has mostly been regarded as an opportunity to safeguard the nation’s food supply, not as a viable option for a new home.

A looming issue still to be addressed is the lack of an internationally accepted framework that grants protection to people already forced from their homes. Under current international refugee and human rights law, there is no effective and uniform recognition of climate change as a driving factor of cross-border displacement. This is demonstrated by the lack of a commonly accepted definition of “climate refugee” and by the absence of legally binding treaties that ensure human rights protection for climate-change-affected people.

Kira Vinke of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research is developing a proposal for a travel document—or climate passport—that might allow climate displaced people to live and work in countries that are largely responsible for global emissions. Vinke said that the climate passport would allow people to claim an entitlement to relocation rather than be subject to government edicts. As mitigation of climate change becomes less and less feasible, migration is one of the only responses remaining.

“We’ve been trying to lower the rest of the world’s emissions for years, but now we’re at a point where we can’t just focus on mitigation anymore,” said Kathy Jetñil-Kijner, a poet and the United Nations climate envoy for the Marshall Islands. But, she added, “I don’t see anybody opening their doors anytime soon or welcoming us.”

Currently, there are limited arrangements between islands that have experienced environmental ruin and powerful countries responsible for the damage. The United States and the Marshall Islands negotiated a Compact of Free Association in the 1980s that entailed U.S. financial aid and extended the right to live and work in the U.S. to the Marshallese, in part as restitution for conducting 67 nuclear tests there. Meanwhile, Australia and New Zealand have made various agreements to take in a few thousand migrants, often for “labor assistance reasons,” from nearby Pacific island countries every year. This extremely limited patchwork of bilateral agreements can’t accommodate the growing number of climate refugees in need of new homes.

“World leaders know exactly what’s happening to people like us in Kiribati,” said Anterea. “Looking at our neighbor, our big brother Australia, they haven’t taken any major sacrifices to support us.”

To remain in a sinking country might seem an impossible task, and yet there may be a workable solution, one that Tong called his “first preference.” He is referring to the principle of raising islands, either through the elevation of their existing land or building artificial ones in their lagoons by dredging sand and gravel—an option currently under consideration by the Marshall Islands and other Pacific nations.

Tong thinks it’s only a short-term possibility for the people of Kiribati, though: “It may give our homeland another 100 years, but eventually the islands will go.”

Chip Fletcher, a climate scientist at the University of Hawaii, has been a strong advocate for island raising nonetheless. Fletcher explained that the Maldives have already taken this approach by dredging material on the island surface and adding vertical elevation an average of two meters high in certain parts, which is what he believes all these atoll nations need to do in order to “stay alive.”

In spite of the potential need for other more long-term solutions, Jetñil-Kijner argued that the Marshallese and other neighboring nations are taking responsibility for their own situation and doing what they can with what they’ve been given. The last thing people want to do is move. Jetñil-Kijner explained how she grew up in the diaspora and knows what it’s like to be separated from land, to be separated from culture. “Staying in our own country is the best option right now and given the climate of immigration rates around the world,” she said. “Building and planning for a disappearing island, envisioning a completely new kind of landscape for our people. That’s definitely visionary thinking.”

If you want more border stories, check out this additional package which explores how the borders that divide and surround Europe affect the lives of the people living near them.