When he started writing a novel about a Wall Street investment banker in late 1986, Bret Easton Ellis didn’t know it would become a serial killer story. In fact, he’d envisioned American Psycho as a book about a guy who couldn’t handle the pressure of his career. But when he started doing research and spending time with bankers in the New York financial district—hoping to figure out how they’d become so successful at such a young age—he noticed something strange.

These men, Ellis realized, were obsessed with speaking about their lifestyles, focused on superficialities, like having fit bodies and immaculate hair. He wasn’t sure what exactly made him change the story, but it was then that he decided to make his protagonist, Patrick Bateman, a serial killer. The novel, which follows Bateman as he climbs the corporate ladder while leading a double life as a murderer, killing multiple women as well as one of his co-workers, horrified readers with its extremely detailed accounts of the banker’s sadistic methods. “It was mostly terrible reviews,” jokes Ellis. “If there were a Rotten Tomatoes for books, it would’ve gotten 0%.”

Videos by VICE

Gloria Steinem was one of a number of prominent feminists who expressed outrage over a novel that featured scenes where Bateman tortured women. After director Mary Harron turned it into a film, though, the story would become the basis for one of the most prominent works of feminist cinema of the early 2000s. Co-written by Harron and Guinevere Turner, the 2000 dark comedy offers a biting, satirical look at toxic masculinity, inviting us into a world where the men around Bateman are so oblivious to his psychotic tendencies that he literally gets away with murder.

The film had a rough start. It changed directors and screenwriters numerous times, each with a different vision for what the film should look like. After originally attaching David Cronenburg to the film, Lionsgate ultimately landed on Harron—only to let her go, and briefly replace her with Oliver Stone, because she was against hiring Leonardo DiCaprio for the Bateman role. Lionsgate eventually realized its mistake and re-enlisted Harron to write and direct. She insisted on hiring Christian Bale for the part, long before he became one of Hollywood’s biggest names.

To celebrate the film’s 20th anniversary, we spoke to a number of central players in the film—including Ellis, Harron, Turner (who also plays Elizabeth, one of Patrick’s victims), and Chloë Sevigny (Jean, Bateman’s secretary)—about the making of one of cinema’s most chilling explorations of sociopathy, masculinity, and capitalism.

First impressions

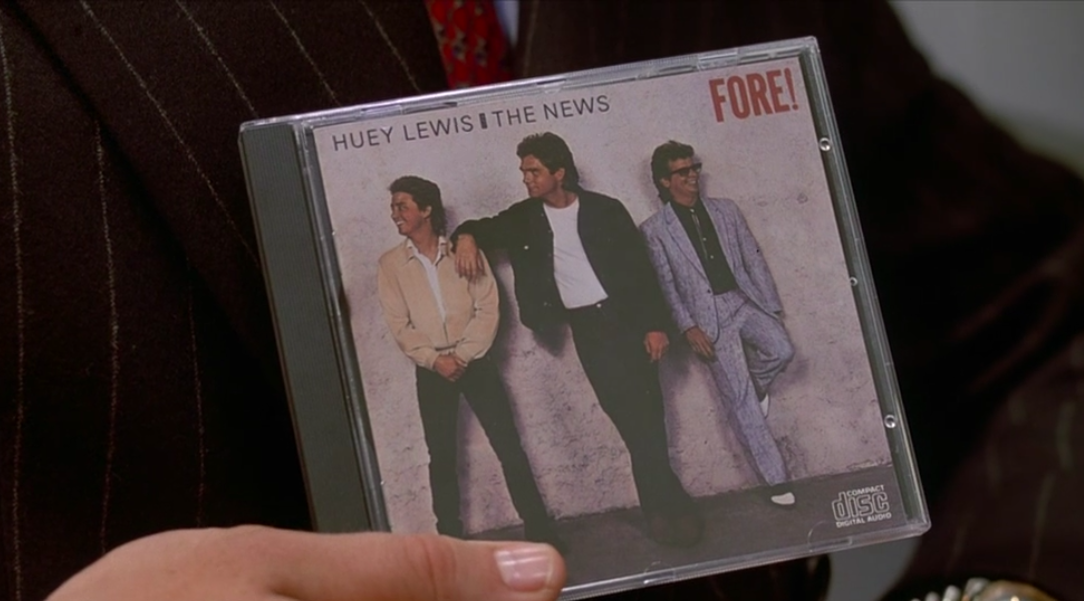

Chloë Sevigny: I remember being really shook by [the book]. There’s a rat with the girl’s cooch, and I’d be like, “Why are we making this movie?”, but then feel kind of okay that the script wasn’t as gnarly. I remember being like, “Wow!”—just liking that kind of writing in that time of my life, that he would dedicate a chapter to things like Huey Lewis. I was thinking it was really cool. I was also like, nineteen years old.

Mary Harron: The thing that I really liked about the book—despite it being ultra-violent—was the way it was kind of slippery. The book would change from the third-person to the first-person narrator. It made quite an avant-garde novel. I knew that the first-person-to-third-person thing didn’t capture [on film], but the thing I did want to capture was that you would have a chapter of pure social satire, and then the next chapter would, with no warning, be horrific violence. I did want to capture the daytime social world and nighttime horrible world.

Pre-production

Bret Easton Ellis: [The American Psycho adaptation] was very surprising, because there was nothing in the book that you would think would make a “mainstream” American movie. There was nobody in line asking to buy American Psycho or option it, except for one producer, and that was Ed Pressman. He became somewhat obsessed with the idea of turning the book into a movie.

He began optioning the book for a fair amount of money, on a yearly basis. My agents at the time thought, “This is the only money you’re going to get.” I remember it being fairly high, and that Ed would be paying out every year to find a director, get a script written, and hopefully attach an actor to it. That went on for many years until the book was finally bought by Lionsgate, and they turned it into a movie.

Harron: I got a call from a woman named Roberta Hanley, who ran the production company that had the rights to the novel. I had read the book, and it had intrigued me. I wasn’t sure if I could make a movie out of it, but I said, “I’ll write a script and I’ll see.” I think the first thing that occurred to me was that just enough time had passed that you could make something set in the 80s, and it would be a period film.

Guinevere Turner: How [Mary and I] started working together was not on American Psycho, but on our film that came out much later, The Notorious Bettie Page. I hate scary movies, but she was like, “You’re going to hate me, but please read this book, because I think we can make a funny feminist movie out of it.” I was reading the book and [thought], “Oh my, this is the most horrifying thing ever and it’s hilarious, and I can see us making a good movie out of it!” So I said, “I do hate you for making me read it, but I’m in.”

Casting Trouble

Harron: [Lionsgate] fired me because I didn’t want to make it with Leonardo DiCaprio; I wanted to make it with Christian Bale.

Ellis: She was interested in this Welsh actor Christian Bale, who [was known] mostly for children’s acting and independent movies—but he wasn’t really a star. I thought that was fine.

Harron: [Christian] had the right look and the right sort of inner mystery; you couldn’t get to the bottom of him. I thought he was the kind of actor that could play bad. And he’s funny. We had the same sense of humor.

Besides him being a great actor, we saw the part in the same way. I felt very committed to him.

Ellis: Lionsgate went to Leonardo DiCaprio—it could’ve been 1998, after Titanic, and he was a huge star—and said they would pay him 20 million to pay Patrick Bateman. He was interested; he wanted to do it.

Mary, for whatever reason, did not want to do it with Leo. And I think that’s when Oliver Stone stepped in, and was going to do this with Leo starring. Christian was jettisoned, and Mary was off the project.

Turner: When Christian was on board and we were super happy with him, all of the sudden it was going to be Leo DiCaprio. It was shocking, because it was all of the sudden announced in Variety that Leo DeCaprio was going to be the star of it, and he had just come off of Titanic.

Harron: I knew that this was like the fourth script of this project for many years; no one had been able to make it work. Then Guinevere started to write it with me, and in the version that they really liked, that brought the project back to life. [But] DiCaprio meant more than I did. Nobody was very concerned about me.

I know that [Pressman] did want me to do it, and he did want me to meet DiCaprio. I said no, because I didn’t want to start down that road. I knew I would find him charming, and then I would find myself getting into doing it with him. You have to trust your instinct, or else it’s going to be a disaster. They would change the script and try to make the character more sympathetic, and it was just going to lose anything it really had.

The other thing that I thought was, Either I do this, or I don’t. But if I’m going to do it, the only way I can make a success of it is to have total control of the tone.

Ellis: Ultimately, [having Leo] did not work out. Leo supposedly—this is the story—got cold feet.

Turner: I believe I’m the one who started that rumor. I mean, I don’t know if it’s a rumor. My friend, who had just spoken to Gloria Steinem, said that Gloria Steinem took Leonard DiCaprio to a Yankees game, I believe, and said, “Please don’t do this movie. Coming off of Titanic, there is an entire planet full of 13-year-old girls waiting to see what you do next, and this is going to be a movie that has horrible violence toward women.”

Soon after that, Leo dropped out, so who knows what really happened? Gloria Steinem ended up marrying Christian Bale’s dad, which is really interesting. I wonder what Thanksgiving was like!

Harron: [Lionsgate] had a wishlist of directors who were all very famous, and they ended up with Oliver Stone, and he pursued it for a while, and I know that they had a reading; Guinevere called me, and said she heard that Oliver Stone had a reading in his office of American Psycho of our script, with Leo DiCaprio, and Cameron Diaz, Jared Leto—just a bunch of other people.

And at the end of the reading, they were discussing how to change the script, basically.

I was quite shaken by the whole thing. But also, I think [it was the moment that] I finally grew up in the movie business—[I] had no idea how disposable I was. I was alone in that, except for a few people who supported my decision, including my husband. But I picked up the pieces.

A few weeks later, my agent called. I thought she was calling to offer me compensation, but they wanted to give me the movie back. They couldn’t agree on the script changes, and DiCaprio decided to go off into The Beach. They said, “She can have the movie back, but she cannot mention Christian Bale.” But I knew eventually they would give in.

Bringing Patrick Bateman to life

Ellis: I remember meeting [Christian Bale] for the first time, and he was dressed as Patrick Bateman. This was here in LA, and I think we were going to meet Mary Harron for dinner, but I was supposed to meet Christian at his hotel first. The door opened, and it was Christian with the haircut, and he was in full-on character—shaking my hand, talking to me. I don’t think he said, “Hi, I’m Patrick Bateman,” but I got the idea very soon that this was [method acting].

We drove down to the restaurant and met Mary, and he was still in his Patrick Bateman mode. I finally had to tell him, “I get it, I get it. It’s really unnerving me; I don’t know if I can do this all during dinner.”

Harron: One thing I said was, “Christian, have you ever been to a gym? You might want to get a gym membership or something.” He physically transformed in a matter of months. But we were also talking about the inner life of the character—how, in a way, he is a kind of monster, a deformed human being. When you’re talking about the character, you’re not talking about a real person. He doesn’t know how to be a human being, so he’s getting those ideas through videos, or pornography. And then he has a kind of panic of social anxiety and feels he’s never doing the right thing.

Turner: He only spoke in his American accent, and he had radically transformed himself since he came into audition. He became completely ripped, super tan, got his teeth turned into perfect American teeth. I think he said he was modeling himself after his lawyer, or his agent, or Tom Cruise—an amalgam of those. He didn’t socialize, and he didn’t break character. There were times when Mary and I looked at each other, like, “Wow, he’s going for it!”

Harron: He maintained the accent… I know other British actors who do that. You want to keep the rhythm going; it’s not easy to maintain. It’s probably different for him now, because he’s been around for a few years, but at that point, I think he wanted to hang on to it.

Sevigny: Obviously, it was a hard part. I mean, the poor guy! I remember doing a play [ Hazelwood Jr. High] where I had to sodomize a girl with a tire iron on stage every night, and I started going to church again.

The iconic Paul Allen murder scene

Turner: [Mary and I] wound up getting a bungalow in Rosarito Beach near Tijuana, Mexico and just reading each other passages and being like, “All of his music rants are just rants. They have no plots to them; they’re just rants about Huey Lewis and Phil Collins.” One of our biggest struggles was, How do we make this cinematic? How do we fit this into the plot?

Harron: I realized that before [Patrick] kills somebody, he started talking about music. So he starts talking about Huey Lewis, and then when he has the girl and the prostitute over, he starts talking about Whitney Houston. And then you kind of know that something is going to happen. That was my one good idea in the movie! It’s funny, because what people like about it is the dark comedy.

Ellis: A lot of it is taken from the book—down to the newspapers, down to the dialogue about the Chow [dog]. She did put in the record reviews with Huey Lewis, which is not in the book, [but] I thought the whole sequence looks [good]—and the killing looks great, the way it’s staged. It’s bloody, it’s violent, but it’s not overly gory. It’s not so upsetting that you have to turn away. It’s done with the perfect aesthetic.

I thought it was great, except I was a little bit bothered by Christian Bale’s little moonwalk dance—the little jig he does before he kills Allen [Jared Leto]. I’ve grown to like it now.

Harron: When the movie came out, Bret did a review of it for some men’s magazine and sang [Christian’s] praises, but he thought it was over-the-top that Christian does a moonwalk. Which is funny, because that wasn’t in the script; Christian just did that on the set.

Huey Lewis: So [“Hip To Be Square”] comes out, and somebody tells me, “You gotta read this book American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis, because there’s like, two or three pages on you in there.” They read me the excerpts, and wow! I was impressed that Mr. Ellis had obviously done his homework. He’d listened to our music, and he drew certain conclusions, and they were pretty spot on, actually.

Then they asked if they could use the song for the film, and I said, “Sure,” and they paid us for it. Then my manager called me and said, “Look, the movie American Psycho is coming out pretty soon, and they want to do a soundtrack album, and they want to put ‘Square’ on it.”

I said, “What do you think about it?” and he said, “Well, frankly, it’s not going to be a very good record; it’s got ‘Hip To Be Square’ and one Phil Collins song, so I don’t think it’s going to be a great record. In a way, it’s almost not fair for our fans to buy this record for just one song.” So I said, “Well, is it part of the deal [of having the song in the movie]?” and he said “No.” And I said, “Let’s politely decline,” so we did.

And then, a day or two before the premiere, they released a press release that went everywhere— to USA Today, The New York Times. It said that I had seen the film, and the scene was so violent that I had pulled my song from the soundtrack, which was 100 percent bullshit. It angered me, and I boycotted the film. I’ve never seen it.

I’m a big Christian Bale fan, so it’s not out of the question—if I could hear better, would I see the film? Sure, probably, at some point. It was just such a Hollywood dirty trick. It pissed me off.

The Threesome Murder

Turner: One of the things we talked about early on when we were tackling the adaptation was, “How do we deal with the violence? What’s the line between telling the story and being exploitative and disgusting?” But we also don’t want to be the lady filmmakers who shy away from the violence or hardcore nature of the original material. So we talked a lot about showing violence off-screen, and then just going for it with one scene. Mary was like, “Let’s just do one classic horror movie scary scene,” though it’s kind of a crazy scene because he drops a chainsaw down the stairwell and kills [the sex worker].

Harron: I remember saying, “I think there has to be a big explosion of violence”—which was of course the scene with the prostitute and Elizabeth, who is also murdered in that scene.

Turner: I did a sex scene with [Christian Bale] where he kills me. You learn a lot about a person as an actor after having to do that kind of scene, and he was great! We actually laughed until we realized we should stop laughing.

It was a hard scene to do because there was a blood packet, and a lot of struggling in the sheets. We had to do several takes, and it was a very intense reset, because the first one, we got blood all over ourselves but none on the sheets, and the big shot was of the blood as it seeped through the sheets.

I was also being directed by Mary for the first time after working with her for years as co-writers, and that was very daunting for me. All the sudden, it’s a completely different dynamic. But Mary said—and I love her for this—”We both hate when somehow, in a scene when two people are naked, we never see the woman’s breasts. I promise not to focus on your tits, if you don’t try to cover them in the struggle.” And I was like, “Okay, fair enough.”

This is a thing nobody knows, but in that same scene, it cuts a little bit from me dying [in the bathroom after escaping from bed] to him chasing her through the bathroom and down the hall in that famous scene, but I’m actually lying face down, covered in blood, in the bathroom. He slips and falls, and she slips, and I’m just there, face-down, my butt and my naked body. I just remember watching that final cut and being like, “For sure, that could have been a body double.”

It was a long day! When you have blood all over you, it’s sticky even after it dries a little bit, so they couldn’t really cover me. So even between set-ups, I’m like, “Hey guys, can I have some water? Can’t really move for continuity.” I’m like, “You can’t even tell it’s me! Nobody knows that’s my bloody ass!”

One of the funniest memories for me was walking into the makeup chair one day when we were shooting the scene where Cara Seymour [who plays the sex worker] is running away from him—same scene I’m in. In the scene, Cara rips open a closet door and there are two women in body bags, and she screams and slams the door. In real life, those actresses were standing there in full dead makeup, which looked horrifying, and they were eating egg salad sandwiches, which smelled horrifying, and I was just like, “Ugh, what I am I doing?” And they were like, “Hi!,” super sweet. And I was like, “Hey girls!”

The Reception

Turner: I met Gloria Steinem in person—I don’t know, five years ago? Just at an event, and I was with a friend of mine, and I was like, “Don’t mention American Psycho. I don’t want her to hate me.” And my friend blurts out, “Hey, she wrote American Psycho!” and I was like, “Goddammit!” I don’t know if Gloria Steinem heard what she said exactly; I think she just heard the words “ American Psycho” and she was like, “I think the women who made that movie were sexually molested as children.”

Harron: I remember people saying, “How can you, a mother, make a film like this? How did you make this film after Columbine?” But what does this have to do with Columbine? You can take any vile thing that’s happened and blame a movie for it, and it has absolutely nothing to do with it.

Nobody knows how to handle disgust and violence. But you know, a few people loved it; some people hated it.

Turner: The hard part, actually, was that a lot of men—and this is still true—identified with it in a way that’s really disturbing. I’ve had so many men say, “You wrote American Psycho? I am Patrick Bateman.” And I’m like, “Oh my god.”

I just saw this documentary called Don’t Fuck with Cats, and American Psycho was one of [convicted murderer Luka Magnotta’s] favorite movies. The first time he kills and puts it on the internet, he plays a song that is in the opening scene of American Psycho—very clearly an homage to the movie. That’s a little bone-chilling when I was watching that. I was like, “Okay, that’s real, there’s a fucking serial killer who saw American Psycho, completely identified with it, and decided it would be the soundtrack to his own first human kill.”

I guess at some point, you have to let go of something like that and realize you put art out into the world. If you feel you’ve done it responsibly, what happens with it is what happens with it.

The Legacy

Ellis: I think the movie is better now than it was 20 years ago—not only in being a time capsule, but also in being an indie movie that could be done on that scale, and be that daring, and push buttons, and examine misogyny and toxic masculinity, but in a non-earnest way. Like, this is a horror film, and it’s going to be poker-faced, and we’re not going to explain anything to you or hold your hand. That neutrality that Mary brought to it is why it’s aged so well.

Sevigny: Most of my memories are involving people outside of what was happening on set. Like, I was dating a boy from England [Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker] at the time, and he was supposed to come visit, and he hadn’t got on the plane, so that whole experience is very colored by that happening to me, and being in love with someone and him not coming, and then finding out it was because he had another girlfriend. That kind of trumped, for lack of a better word, the work I was doing.

Turner: A lot of people who didn’t get it, get it now. And lot of women in my life said ten years later, “You know, I just assumed that was a horrible slasher movie and I never saw it, and then I saw it and realized it’s a smart feminist critique of masculinity.”

I’m like, “Gosh, for the last ten years, you’ve just been thinking I’m a weird sell-out? Like, sure I’ll do a slasher movie—whatever pays the bills!” Mary and I laugh about it a lot—we felt like pariahs for a while there. We felt misunderstood. Now we feel vindicated.

Harron: I always thought the book had a critique about masculinity. That’s something we took from the book, but I think we cleared away a lot of the extreme violence so you could see what that critique was.

People couldn’t see the critique, because they were so upset by the violence, but what’s interesting—and why the book has lasted and why the film has lasted—was that it’s saying something interesting about how our culture operates. You take everything that’s really terrible about our culture in the late 20th century and you press it into one person, and that’s Patrick Bateman.