This article originally appeared on VICE Germany

In a 1934 letter to American sociologist Theodore Abel, Helen Radtke explained why she had joined the German Nazi Party. She wrote that she was a politically active person who had sat in the public gallery of her local state parliament to listen to the debates held there, and attended as many political rallies as possible in search of a party that was “nationalist, but also cared for the poor”. Eventually, she wrote, she found just what she was looking for in Hitler and his movement.

Videos by VICE

Radtke’s letter was just one of 683 personal accounts sent to Abel in the years after Hitler was elected in 1933. Last January, the Hoover Institution – a public policy think-tank based at Stanford University in California – published 584 of those letters online. These personal testimonies are not only useful in understanding why so many people were attracted to the Nazis in the 1930s, but also provide insight into the minds of the millions of Germans today who are still turning to far-right political parties, like the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD).

Around a year after Hitler became Chancellor, Theodore Abel wanted to know what had motivated so many people to support him. After Abel failed to get any of the estimated 850,000 Nazi party members to agree to an interview, he came up with the idea for a fake competition, where he offered 125 Reichsmarks to whomever could write the most beautiful, detailed description of why they had joined the Nazi Party.

WATCH:

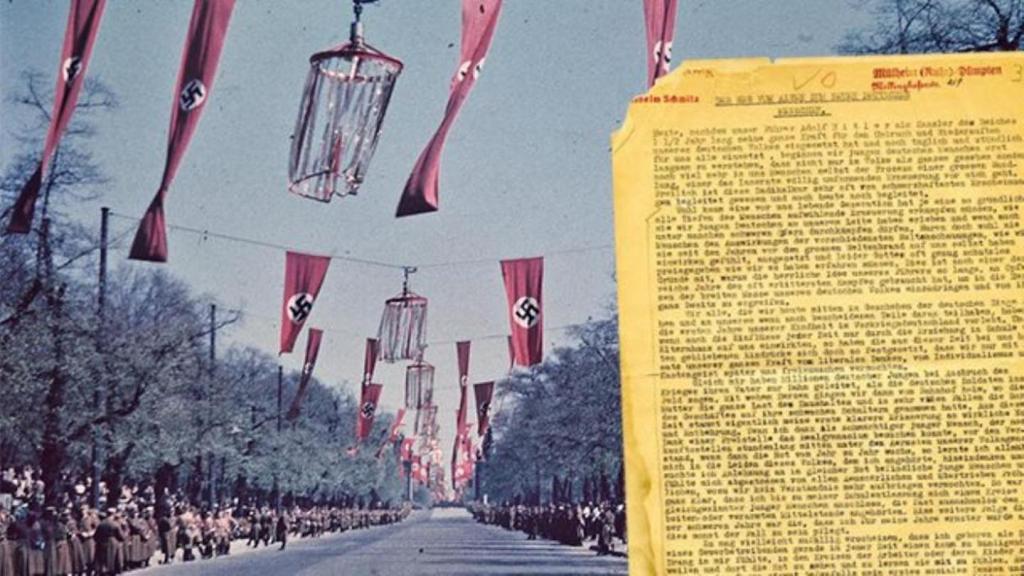

At the time, the prize money was worth more than half the monthly average salary in Germany, and even Joseph Goebbels – the Nazi Minister of Propaganda – publicly supported the contest. The submissions ranged from handwritten love letters to Nazism, to 12-page testimonies, while participants represented a cross-section of German society, from soldiers and SS officers to office workers, housewives, children and miners.

Many of the letter writers were happy to see the end of the Weimar Republic, which was founded in 1919 after the German defeat in the First World War, and which they blamed for the economic state the country was left in after the war and for the Great Depression. The writers were excited by Hitler’s promise to introduce strict political order; Bernard Horstmann, a miner from Bottrop in western Germany, wrote that he thought the previous government had promoted “the betrayal of the people and our fatherland”.

Horstmann went on to call a professor who thought the First World War was unjustified a “poisoner of people’s minds”. Before joining the Nazis, Horstmann was a member of the antisemitic nationalist group the German Völkisch Freedom Party, but soon, he wrote, the group’s ideologies became too tame for him.

A letter from Ernst Seyffardt from Duisburg, another city in western Germany, was titled: “The Curriculum Vitae of a Hitler-German”. Seyffardt wrote that he joined the Nazi Party because he wanted to contribute to “bringing back peace and order in our homeland”.

WATCH:

At the time, left-wing groups tried to counter the surge in nationalist support. Fights would often break out between Communist Party members and thugs from the Nazi paramilitary wing, the Sturmabteilung (SA), while some more liberal groups called for the boycott of shops owned by Nazi Party members. But that only seemed to make Hitler and the Nazis more appealing to many. “It was because Adolf Hitler and his party faced so much criticism and resistance among the press that I became particularly interested in joining their movement,” wrote a party member named Friedrich Jörns.

The letters Abel received reveal that the right-wing information bubble prior to 1933 largely stemmed from the weekly newspaper Der Stürmer, Hitler’s Mein Kampf and Nazi Party rallies.

One member, named Schwarz, explained how reading Mein Kampf had caused him to not only distrust most mainstream newspapers, but also Jewish and Polish people for the way their “catastrophic, mole-like activities have ruined the world”. Even though Schwarz went on to admit that he had never had personal contact with anyone Jewish, and that he couldn’t prove that Polish people were “unreliable”, he wrote that he “trusts his instincts on the matter”. Nurse Lisi Paupié clearly agreed: “The Jews are our misfortune, that much is clear,” she wrote in her letter to Abel.

Recently, the German television show Panorama had three actors read out some of the letters, partly to show how the rhetoric used – “old parties”, “dreadful press”, “poisoner of minds”, “betrayal of the people and fatherland” – is similar to that used by the AfD. And the segment proved its point: those terms are still worryingly relevant almost 85 years after Theodore Abel decided to trick some Nazis into writing their letters.