Freedman Files is a new column exploring the personal photographic archives of veteran photographer Jill Freedman. The archives we will feature span subjects and eras, and include some previously unpublished work. Freedman became riveted by photography as a child when she found copies of LIFE with articles documenting the Holocaust in her attic. As a young woman, years later, she couldn’t forget the formative experience, and she decided to pick up her own camera to tell stories that would reach people in the way those images had moved her.

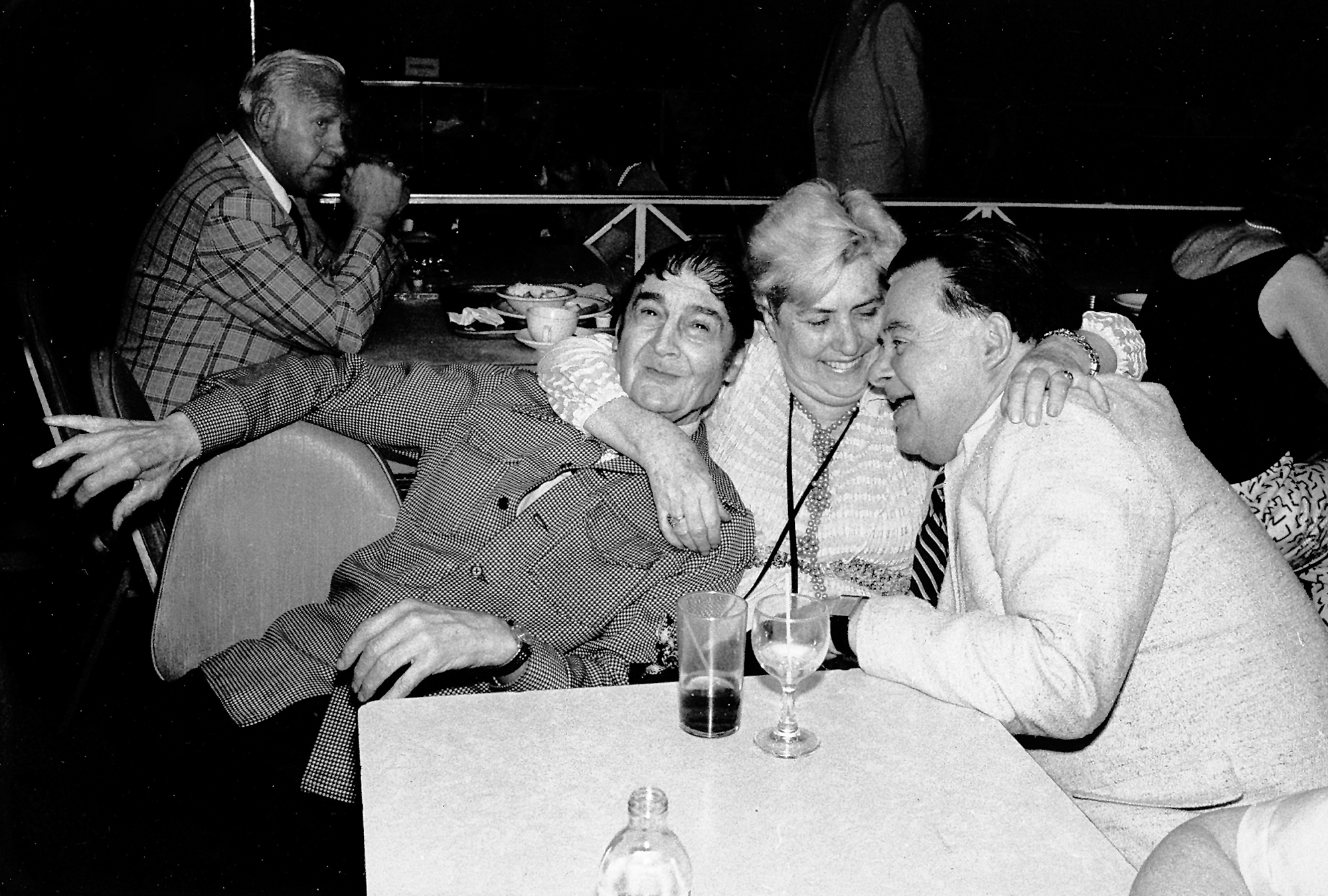

The first collection in Freedman Files comes from two of Freedman’s visits to New York’s Roseland Ballroom, the legendary nightlife venue—one from the 1970s, and the other from the 1980s. In Freedman’s words:

Videos by VICE

“Roseland was one of the best things about New York, a real ballroom with two bands where you could meet people, have some drinks, some laughs, dance your fool head off. Roseland was a United Nations of dancing fools—all sizes, all ages, the whole world having fun. You can’t help smiling when you dance; you just feel too good.

“People touched when they danced back then. The music didn’t deafen you. There were even matinees twice a week, and it was a great way to spend an afternoon, instead of sitting alone in front of the tube feeding your face or hacking off in a chat room.

“Once there was a Ballroom of Romance, but it’s a disco now, gone like Penn Station, the Old Met, a great egg cream. You may listen for the lullaby of Broadway, but you won’t hear it.”

The lullaby she references comes from an old show tunes song she grew to love from 1930s and 1940s Hollywood movies absorbed in her youth. For Freedman, “Lullaby of Broadway” speaks to her childhood hopes and her love for the city of New York that she has made her home time and time again, beginning in 1964. Watching the movies as a kid in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Jill expected their storybook endings to occur in real life later on. Although she suggests that life does not regularly pan out as such, a feeling of movie magic is what led to her photos of the ballroom.

Freedman first attended a concert at Roseland without her camera, and she danced to Count Basie and the big band that accompanied him. As Basie played, Freedman felt as if the dreamy silver screen had come to life: “I loved it,” she said. “Dancing to a big band, that’s how I thought it was gonna be when I grew up.” People were happy, socializing, flirting—here and there with occasional bouts of loneliness. So she thought it needed to be photographed.

Freedman later returned to one of the venue’s matinees wearing her camera. She paid for entry just like everyone else. Once inside, she smiled at the other guests and began snapping photos. “That’s what happens when they know you’re not threatening,” she told me. “When they know you’re into something and loving it, they get it.”

Freedman loved Roseland because it was “real New York, old New York.” Patrons talked to her and let her take their pictures. She says that there were quite a few elderly people there who danced fantastically.

When changes came with time to this environment where Freedman felt she found so much warmth, she was deeply angered. “Another reason to hate disco,” she reflected. When disco arrived, Freedman felt that it was mechanical and noisy. She first heard it blaring from a wall of speakers, what she described as straight squares blasting sound.

“My first thought was, This is going to put a lot of musicians out of work,” she recalled. “I was right.” She had come of age when musicians who performed live always played instruments, and she witnessed how they had to work—really work—onstage. She also understood the live musician’s way of life; as a young woman, she had made her way through Europe by singing and busking. She had a good voice and knew some basic chords, so she played on the street and in clubs, which she says allowed her to make enough to “live, wander, and explore.”

For Freedman, discotheques seemed like the end. To hear her tell it, in place of human connection and live music came the loud, banging noise of a drum machine. She lamented, because what always struck her about Roseland were the relationships between people. Besides bodies twirling together, “you could talk and hear each other.”

But she didn’t say much to anybody during the two visits to photograph Roseland, decades before it fully transitioned to a venue for hire and eventually closed in 2014. Searching for potential images made it difficult for her to split her attention. “When I’m really looking, like in the street, I can’t talk,” she said. “There are times you can’t talk… Those are the times when I feel it, so I go and see if I could capture it.”

As she thought back to what she was searching for in these images, “Lullaby of Broadway” came to mind first because Roseland was located at 52nd Street and Broadway in New York’s theater district, and then because of the things she felt it tapped in her nostalgia—like exhilaration for the city’s everyday details, and a sense of togetherness among strangers. The song was written by Harry Warren and Al Dubin for the 1935 Busby Berkeley film The Gold Diggers of 1935 and covered by many performers since then. Freedman still sings it easily from memory, and the beginning goes like this:

Come on along and listen to

The lullaby of Broadway

The hip hooray and ballyhoo

The lullaby of Broadway

The rumble of a subway train

The rattle of the taxis

The daffodils who entertain

At Angelo’s and Maxi’s

When a Broadway baby says good night

It’s early in the morning

Manhattan babies don’t sleep tight

Until the dawn

Good night, baby

Good night, the milkman’s on his way

Sleep tight, baby

Sleep tight, let’s call it a day

Listen to the lullaby of old Broadway

When pressed about why it catches the spirit on the dance floor at Roseland, Freedman exclaimed, “It was that whole thing you’d move to New York for as a kid that you can’t get anymore! Where you’re up all night, and you’re coming home at dawn hearing the taxis.”

Roseland and the lullaby are just a single strand in the enchanted vision that forms a large part of Freedman’s photographic viewpoint: the fleetingness of the present, the innocence and joy in a complex world of challenge and trauma. This batch of her photos draws from something that will forever remain, despite the bruising that experience gives you.

As she says, “To this day I long for the waltz… in the arms of your prince like in the movies. I, in chiffon of course…”

Freedman’s works are included in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the International Center of Photography, and George Eastman House, among others. At 77, she posts regularly to her Instagram account , and is represented by Steven Kasher Gallery, New York. In the future, Freedman intends to publish more photo books to augment the seven she has released to date, including Firehouse and Street Cops, which are featured in Cheryl Dunn’s 2013 documentary on street photographers, Everybody Street .

—Words by Cameron Cuchulainn

More

From VICE

-

Carlos Idun-Tawiah -

Photo by ENNIO LEANZA/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock -

A gang of men hide in a clown car at the Ringling Brothers Barnum and Bailey Circus. April 1977, New York City. -

Screenshot via NY Post