NBOMe isn’t new to Australia, but it is now reaching a previously unseen level of notoriety. This process of public familiarisation seems to have come to a head in January this year, when three people died and 20 were hospitalised after taking what was initially described as “a bad batch of MDMA.”

But as VICE revealed Monday, Victoria Police analysed the suspect drugs a week later, concluding they contained “a cocktail of illicit substances, including 4-Fluoroamphetamine (4-FA) and 25C-NBOMe.”

Videos by VICE

Retrospectively, it now seems likely the same batch was responsible for a similar spate of Gold Coast hospitalisations in October 2016. Additionally, NBOMe was blamed for the death of Tasmanian man Rye Hunt back in June after he took what he thought to be MDMA in Brazil.

Now newspaper reports are losing the quote marks around NBOMe. In the space of a year, Australia has learned of the existence of a relatively new and untested research chemical that only hit illicit markets around 2010. And by untested, we mean that very few animal studies have been produced, its overdose limits are largely speculative, and it comes entirely without any large-scale human studies. Concerningly, a large-scale human study is now underway in the general population.

So what is it?

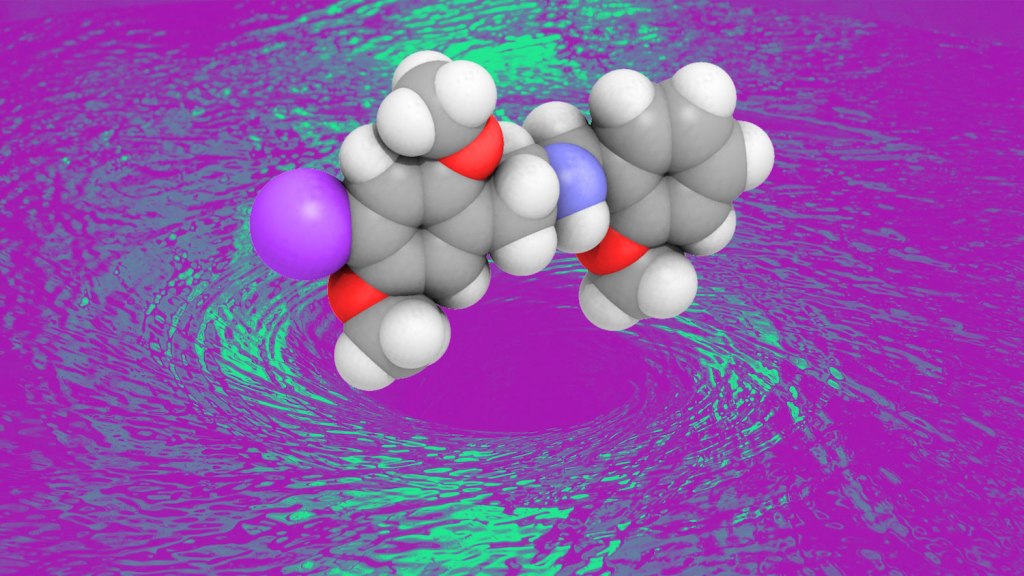

N-B-OMe stands for N-benzl Methoxy and belongs to class of drugs known as phenethylamines. Other drugs in this group include MDMA, methamphetamine (known colloquially as ice), cathinone, and 2-CB. These are a class of powerful stimulants, which structurally speaking have nothing to do with LSD. It’s important to note that while NBOMe often gets described as “synthetic acid,” the two drugs belong to different families, although they do target the same parts of the brain.

NBOMe is a powerful agonist, meaning it binds to the brain’s serotonin receptors and manipulates the way they function. Specifically the drug binds to the 5-HT2A receptor, which is also the same target for LSD and a range of antipsychotic drugs. As an interesting side note, autopsies on the brains of suicide victims have found more 5-HT2A receptors than in normal brains, although the correlation betweet receptor numbers and depression is poorly understood.

Where did it come from?

NBOMe was first synthesised in Berlin in 2003 as part of the PhD work of a chemist named Ralf Heim. Unlike Albert Hofmann, who first created LSD, Heim has never given interviews and today lives a fairly subdued life in Frankfurt. Instead it was another chemist, American psychotropic-enthusiast Dr. David Nichols, who brought NBOMe out of obscurity.

As Dr. David Nichols explains in the above video, he first synthesised NBOMe for a lab study in 2007. He published his results in much the same way as Ralf Heim, the only difference being that Dr. Nichols enjoys something of rockstar following online. As a quick example of this, try googling his name. You’ll find result number three is a Reddit thread titled “OH MY GOD I emailed Professor David E. Nichols… AND HE RESPONDED WITHIN A DAY.”

Several of Dr Nichols’ research chemicals have made their way onto the black market, but NBOMe has likely carved out the most harm. As he describes in the video, “It’s the paradigm of science: you publish your work so people know. I just feel sad that people make the kind of irresponsible decisions that lead to those kind of tragedies.”

How does it kill people?

To answer this question we reached out to Dr David Caldicott who is a senior clinical lecturer at the ANU medical school. David also works as emergency hospital consultant where he’s seen NBOMe patients admitted with a range of symptoms. While these are often the result of psychosis-induced injury, David says it’s drug’s effect on the cardiovascular system that’s the real problem.

“NBOMe creates problems by thickening the blood and thinning the blood vessels,” he explains. “This is the main catalyst behind a range of other issues including ventricular fibrillation leading to heart attack, renal failure, and even stroke. These are conditions that no self-respecting 20-something year old is normally entitled to have.”

In this way NBOMe is different to most other hallucinogens. There has never been a recorded overdose with LSD, mushrooms, or mescaline. But NBOMe’s blood clotting effect, overall toxicity, and extreme potency make it unique. This is a point made clear by David, who relates the story of a 20-something year-old patient he saw in 2014.

“This young man was not unfamiliar with drug consumption and wisely decided to take one quarter of one pill. Not long after he decided to admit himself and came into our hospital with a deranged heart-beat, from just a quarter. If he’d taken the whole thing he’d probably have died.”

Is it orally active?

Spend some time googling NBOMe and you’ll find a lot of discussion about whether the drug is active when swallowed. The belief is that it only affects people who break the caps open and sniff the contents, or rub it over their gums like speed. But there doesn’t seem to be a consensus on this, so again we turned to David.

“What we do know is that it seems to be mucosally active, because traditionally it’s been available as a blotter that dissolves in your mouth. So, if you put it in your mouth and hold it there for a matter of time, it’s entirely possible that there will be some uptake. Although it’s certainly not as active orally as it is through other routes.”

What should we do about all this?

This is where things get political. Like prostitution, gambling, and drinking, drug taking will continue for as long as humans chase pleasure. Many governments internationally have accepted this and reacted accordingly. Tragically, Australia has not. So while cities in Europe allow and facilitate drug testing and issue public warnings about dangerous evolutions in black market formulas, Australian politicians discuss drug testing as an outlandish endorsement of criminality, while state police actively suppresses information that could saves lives. As Dr David Caldicott expounds, “the priority has got to be keeping people alive, rather than trying to stop people from using drugs.”

“There has never been a more dangerous time to take drugs in Australia,” he says. “When I was involved in pill testing back in the early 2000s there were probably only about 15 drugs of interest to us. Now, two months ago I was in Vienna for a big meeting on psychotropics, and their head of analysis announced the arrival of the world’s 750th novel psychotropic substance. That is what’s happened in the last 10 years, and our public health response just isn’t keeping up.”

Follow Julian on Twitter.