At Bristol’s Love Saves The Day festival, news spreads on Sunday morning that two people have died after taking “dangerous high strength” drugs at Mutiny Festival in Portsmouth.

Outside the tent run by charity The Loop – where festival-goers can get their drugs tested for purity and strength – 67-year-old Chris Lark says: “There were two people killed yesterday, so if [The Loop’s work] stops two people dying, it has to be a good thing.”

Videos by VICE

This is The Loop’s third summer of reducing drug-related harm at UK festivals, with staff testing punters’ drugs, telling them how potent they are and offering them on-the-spot, personally-tailored harm reduction advice. However, where all previous testing has taken place within festival grounds, for the very first time they are now offering a pop-up service in Bristol city centre, in an initiative backed by local police, the council and local MPs.

After two pilot days of testing in May, for the next six months Bristolians will be able to to find out what’s in their drugs, how strong they are and how to take them as safely as possible.

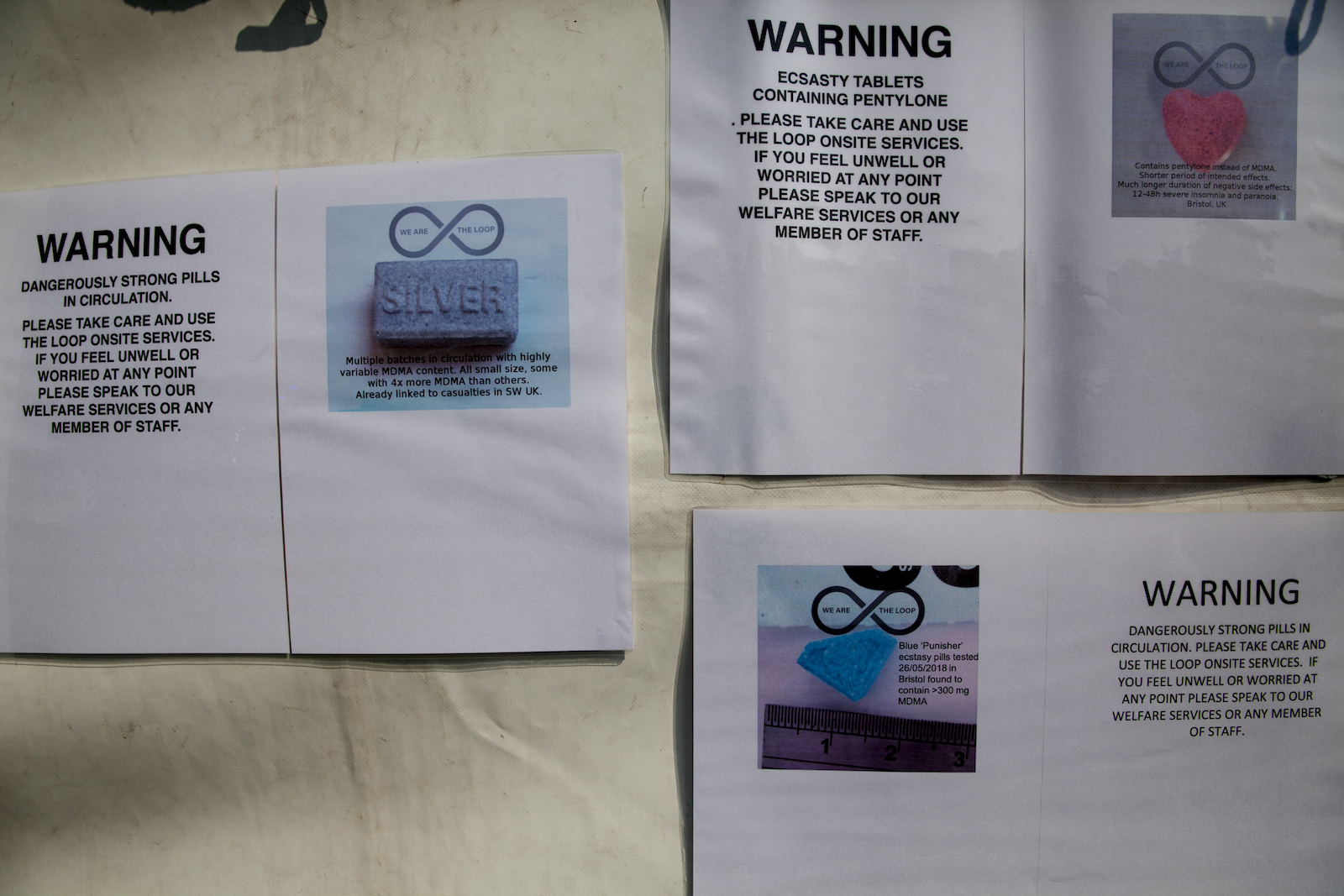

With drug-related deaths on the rise and the strength of ecstasy pills often dangerously high, this information can make all the difference; The Loop – VICE’s partner in our Safe Sesh campaign – have already issued warnings after tests in Bristol city centre found that a heart-shaped pill sold as MDMA was actually N-ethylpentylone, a potentially lethal, long-lasting stimulant that could keep you awake for days.

At Love Saves The Day (LSTD), a blue “punisher” pill was found to contain more than 300mg of MDMA – three to four times the recommended dose – and the strength of Silver Bar tablets varied fourfold. One in ten samples tested at the festival were not what they were sold as: pills turned out to be plaster of Paris, crushed paracetamol was sold as MDMA, antimalarial drug chloroquine as cocaine, and what someone thought was a huge MDMA pill was in fact a Pepto-Bismol.

“This service is important because drug use at the moment is increasing in danger. Young people know less than they ever did before about what they’re taking,” says Henry Fisher, The Loop’s senior chemist.

“A lot of drug use happens at festivals, but also elsewhere, so introducing city centre testing in Bristol allows us to provide a service to a wider group of people – not just typical club drug users, but also potentially opiate users.”

After offering their services at three festivals last year, including Boomtown and Secret Garden Party, The Loop plan to do six in 2018. They also hope to roll out city centre testing to three other places this year, but doing so would require full support from local councils and police.

“We’ve had a lot of police forces and councils contact us because they want testing in their cities, but there’s also still a lot of resistance from government and from areas who aren’t quite ready for it yet,” says Fisher.

The consensus among festival-goers at LSTD, however, is that a drug testing facility is a positive addition to Bristol city centre.

George Taber, a 19-year-old student, got his MDMA tested in Bristol the day before the festival. “This service is gonna save lives,” he says. “You have people buying drugs for the first time – something they think is MDMA, but is spiked with PMA or some other adulterant, which could kill them. It just gives you peace of mind. I know tomorrow I’ll be alright rather than worrying about what’s in my drugs.”

Of the 200 people who have their drugs tested at LSTD, results bring mixed reactions. One guy is happy that his pill was stronger than expected, another is disappointed with the strength of his and says he needs to “go have a word” with whoever gave it to him.

A group of guys have their pink Tesla pills tested, and at 250mg they’re very strong, containing 150mg more MDMA than the average ecstasy pill in 2015. “It’ll slow us down for sure,” says one of the group. “In the past, friends have taken stuff that wasn’t what they thought it was and had weird reactions. We’d rather know what we’re taking.”

Another festival-goer, who is planning to test his coke and ketamine, says: “Every festival I’ve been to, I’ve seen someone on the floor, fucked out of their head, so this testing is a good idea.”

Ella Aylmer, 19, comes to test a baggy she found on the street. She is pleased after it turns out to be MDMA. “It’s good to know, and they gave me good, solid advice about how much to take,” she says. “It’s above average strength, so best to take a smaller amount, which I wouldn’t have known.” She thinks the services offered by The Loop are “brilliant”, because so many people are otherwise “leaving so much up to chance”.

Sam Cooper is another to test his MDMA, which turns out to be stronger than expected. At the age of 33, he wishes he’d been able to test and get advice when he started using the drug over a decade ago. “At the moment, with pills and MDMA, strength is the big factor, and it’s quite scary,” he says, adding that some younger users are “blasé” about what they’re taking. “It’s amazing that it’s also in the city centre,” he adds. “That’s where the majority of the recreational drug use is going on. It’s incredible that the forces that be are allowing them to be here.”

It’s not just drug users who back this harm reduction service. Festival stewards and medical staff regularly have to deal with drugs and their effects, so anything to mitigate these kinds of incidents are welcome. A steward at LTSD says: “Drugs are a massive problem – they can lead to deaths, so testing is a good idea, because otherwise the aftereffects are passed on.”

He adds that, despite strict security checks, “quite a lot of people try their luck”, and “there’s only so much you can stop” from being smuggled in.

While some people would oppose anything that could be seen as encouraging drug use, there are signs The Loop’s testing has some support among older generations.

Stephanie Joromani, a 49-year-old local resident, says: “I’m against drugs. I will never take drugs and I wouldn’t want my kids to take drugs, but if someone is addicted they should be kept safe by checking how much they are taking. I think [testing] will make it safer. There are a lot of people who take drugs behind doors, and it would encourage them to come out, ask how much they are taking and seek help.”

Chris Lark, the 67-year-old at LSTD, says: “All drugs are bad, let’s be quite honest. People will take drugs; kids are dying all the time and they don’t know what they’re taking. If it saves two lives, it has to be worthwhile.”

At the end of the weekend, Tom Paine, the festival’s director, says The Loop’s testing has “gone as well as we could have hoped”.

“Obviously with the tragedies in Portsmouth this weekend, it brings it all home and illuminates even further how important this approach is in preventing drug-related harms. For us, the work The Loop did on-site was great in raising awareness,” he says. “We don’t know if we saved someone’s life this weekend, but we may well have, by somebody taking half a pill rather than a whole one.

“We’re lucky in Bristol that straightaway we got the support of Avon and Somerset Police and Bristol City Council. They’re really forward-thinking organisations.”

Paine says support from all stakeholders is needed for this to work elsewhere, but that now Bristol has set an example, others are more likely to follow.

Thangam Debbonaire, MP for Bristol West, has been an outspoken critic of current drug laws. She says she is glad the council and police have backed the initiative, which “has the potential to save lives”.

“If it is judged to be successful at reducing risk and preventing harm, then I hope ways will be found for it to happen more,” she says, adding that it’s a “significant step towards reducing harm”, but that other progressive policies are also needed, such as drug consumption rooms for heroin users, as part of a “complete review of the law and policy around drugs”.

As The Loop looks for funding that would allow them to set up five regional testing hubs, central government still refuses to back testing or any other harm reduction initiative. But it would appear that in a similar way to drug consumption rooms, commitment from local authorities and police forces can make things happen in pockets around the country. Bristol is leading the way, and by the end of 2018 other cities may well have followed suit.

Matty Edwards is a reporter at The Bristol Cable.