There was a moment filming Stansted 15 – The Fight to Remain that sticks with me. Ruth Potts, one of the activists on trial for breaking into Stansted Airport to stop a deportation flight, was talking about when she’d first realised the terrible injustice of the UK’s immigration system. On her bus to school in Croydon she saw the queues of people snaking out of Lunar House, lining up for their visas from the Home Office. There were people there every single day, even in the dead of winter. When it got cold, volunteers would hand out cups of tea.

“I’ve been there,” I said. I knew Lunar House very well. In fact, I’d committed most of it to memory – its horrible, speckled breeze block exterior, the hospital-like corridors, the sterile cafe perched on the very top floor, full of grimly silent families and their overly chatty lawyers.

Videos by VICE

The afternoon after I visited Lunar House – hopefully for the first and last time – I got on the train home and tried to make myself cry. I was an immigrant; I’d moved here from Singapore as a teenager. I’d just paid over a grand to apply for indefinite leave to remain in the UK, and several hundred pounds extra for a face-to-face appointment at the “premium service centre” at Lunar House. In total, it had cost me close to £1,500.

I had travelled to Croydon with a meticulously detailed folder of documents showing my right to stay in the UK, the sum total of my years spent here – employment records, bank statements, P60s, graduation certificates, council tax bills and letters from my landlord confirming my residence (letters he’d charged me for). After waiting a couple of hours in the Lunar House cafe I was called into a small booth, where an officious woman looked through my folder, directed me to stare into a webcam and disinterestedly took my photo. I’d made the cut.

A few months later, the culmination of all these years of assiduous documentation arrived in the post: my biometric residence card, which now said: “INDEFINITE LEAVE TO REMAIN”. On the train from Croydon, I tried to feel relief. Was I excited? No. Was I happy? I tried to cry just to feel something, but I just felt… flat.

It was only years later that I realised I’d experienced a very small taste of the alienation that comes from encountering our nightmarish immigration system; a system in which people can be reduced to “points” (a few here for speaking English, another cursory few for graduating uni), where records can simply evaporate into thin air, your grandmother can be deported despite living here her entire life, and the complexity and richness of human life can be boiled down to a simple checklist: can you prove you deserve to be here? And, more importantly, can you afford to pay for that privilege?

I tried to explain this to Ruth on the shoot, but the words came out wrong. “Lunar House is, like, haunted…” I said. “It’s like all the horrible psychic energy of the place has cursed it somehow…” Everyone on set looked puzzled. But if you’ve been to Lunar House, you’ll get it. Call it bad feng shui or the cumulative effect of years of human misery from visas denied and applications lost, but you feel it when you’re there. When a Guardian investigation last year revealed a “toxic atmosphere” at the Home Office unit stationed in Lunar House, I wasn’t surprised.

The conversation with Ruth was the first time I’d thought about Lunar House in years. When I got my leave to remain, I instinctively took those memories, tied them to a five-ton weight and sunk them deep below the surface of my consciousness. I was one of the lucky ones. I got to stay. Now, moving on…

Filming the documentary made me revisit that period in my life again. When I met David*, a man who was due to be deported on that Stansted flight, I realised just how fortunate I’d been. He had more to lose than I ever did – his partner had just given birth to his first child – and yet he was the one who had found himself on a bus in the dead of night, being driven up to the aeroplane that would send him thousands of miles away from his family.

By this time, I’d happily dwelled in the “indefinite leave to remain” category for years. I’d probably have been happy there forever. The next step up – applying for a British passport – meant I would have to give up my Singaporean one, as Singapore doesn’t allow for dual nationality, and that felt like a decision I didn’t want to grapple with. I was fine! I was happy! Moving on…

I realised that a function of the privilege that ensured my relatively smooth passage through the immigration system – that I had a degree, a job, spoke English, had money for fees – was allowing me to close my eyes to its reality.

For many of my British friends – white British people in particular – it’s hard to understand, this idea that the machinery of the state is not your friend. It’s the difference between seeing a “go home” van as either a bad omen or a stupid joke; the difference between crossing the street to get away from it, hoping that it doesn’t somehow see you (stupid, I know, but superstition works in strange ways), and taking a picture of it on your phone so you can make fun of it on Twitter later.

It’s the difference between knowing you can send off sloppy paperwork and suffer no consequence, and deliberating for hours over whether a rogue paper clip or staple or blue biro could send an invisible Home Office worker into a fit of rage and tear up your file. Does it happen? Who knows. The online forums where immigrants gather to swap horror stories are awash with tales of missing passports and years of paperwork gone astray. When you send your application into the gaping maw of the UK Border Agency, who knows what might look back? Is a van ever just a van?

The system is not designed for people – it is designed to exclude them, to suppress the numbers, to trip them up. It is like this on purpose, because politicians who have never had to navigate it themselves decided to pull numbers from thin air and set targets that are, to be frank, unreachable.

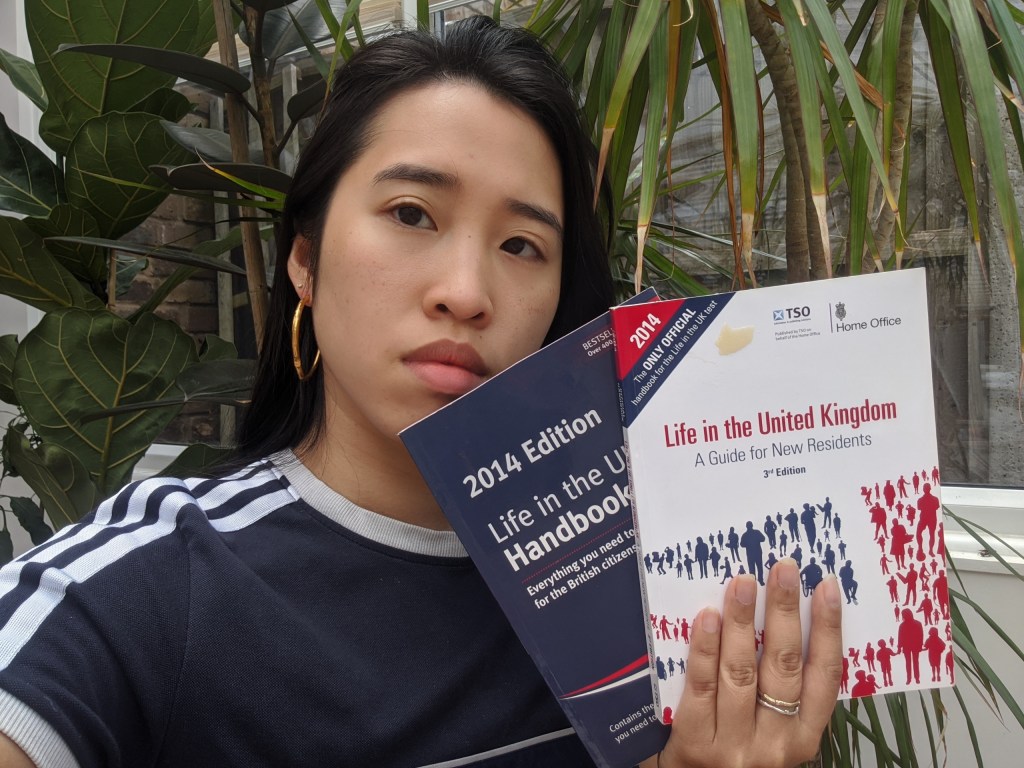

The crowning glory of this all is, of course, the Life in the UK test. Formerly known as the citizenship test, it’s meant to quiz immigrants on how much they know about their adopted homeland, and they must pass it in order to remain in the UK. Of course, this is fundamentally nonsensical – if you aren’t allowed to stay in the UK, how on earth can you know what it means to live here? Here’s a sample of what you might be asked on the test:

Who was Capability Brown?

Who invented the cash-dispensing ATM and where was the first one built?

How many MPs sit in the House of Commons?

All of this information is contained in a book titled Life in the United Kingdom, sold with the Home Office’s approval for £12.99. At the end, the book offers this cheery disclaimer: “Of course, it is impossible for a book of this sort to cover everything. We hope it may have inspired you to go on to read more about the history and culture of the UK.”

I studied Life in the United Kingdom with the fervour of a Gregorian monk laying his hands on a rare manuscript. If I stopped to consider all the ways in which this book was deficient – why did its record of British history stop sometime around 1997? Why were there so few people of colour in it? Why were there 12 pages devoted to the Tudors and the Stuarts, and two paragraphs on the British Empire? – my brain would have dissolved into goo. Better to slavishly devote the following facts to memory:

How to donate blood and organs

The official flower of Scotland

The best-known works of Evelyn Waugh

The irony is, of course, most British people don’t know these facts. Knowing the plot of Brideshead Revisited doesn’t make you any more or less worthy of being British. And yet, through the government’s labyrinthine contortion of logic, this is now the standard we apply to everyone else.

I thought about the Life in the UK test as I recorded United Zingdom, my BBC Sounds podcast. My conversations with people like David and Ruth were the jumping-off point for the show. I’d spent too long happily dwelling in the grey area of indefinite leave to remain, and I wanted to know what it would mean to become British. What did Britishness even mean? What did its passport represent?

During the course of the series, I collected facts for my own personal Life in the UK test:

What do people from Liverpool call people from the Wirral?

What, or who, is the Old Firm?

Locate Northern Ireland on a world map (instant deportation for anybody who draws it inside the island of Britain)

When I asked British people what they thought of Britishness, or what made them proud to be from their hometown, they said things like:

The languages they heard on their street

The greenness of the grass

The smell of their neighbours’ cooking

In the course of writing this article, I looked up how much indefinite leave to remain costs now. It’s £2,389 to apply to the Home Office – almost a grand more than I paid. Can you put a price on belonging?

I’d like to think that Britain is about small, precious fragments of people’s memories and lives more than it is about 15th century kings and thousand-pound surcharges. It’s about the tender ephemera that makes up our daily lives and the people we love – the sound of your friends’ laughter, the sweetness of your mother’s native tongue, the street you live on, the homes we build together. It’s about the soft, unsteady grass beneath our feet, not the maze of paperwork and unjust bureaucracy we build to keep people out.

You can listen to United Zingdom on BBC Sounds .

More

From VICE

-

Photo by Hollandse Hoogte / Shutterstock -

Photo: Frank Hoensch/Redferns via Getty Images -

Collage by VICE -

Collage by VICE