In my high school, you were either a rocker or a guido.

A “rocker,” a term coined and used by the guidos, encompassed anyone who wasn’t into rap, ignoring the several hundred thousand shades of subtlety between Linkin Park and Fugazi. “You a rockah, bro? You like that kill-ya-motha-kill-ya-fatha shit? Like, Marilyn Manson, bro?” By default, I was a rocker.

Videos by VICE

A “guido,” a term used by us dirty rockers, was any kid whose Honda Civic had tinted windows, neon floor kits, comically large spoilers, and any other automotive wastes of pizzeria paychecks that would soon be made famous by The Fast and the Furious franchise. If you blasted Puff Daddy out of it on your way to the tanning salon, you were a guido. Keep in mind this was a full decade before the Italian fishbowl reality sensation Jersey Shore was even a glimmer in the eye of an MTV producer.

For four years, the two social circles seldom crossed paths to agree on anything save for the occasional episode of South Park. Then in my senior year, while the guidos were listening to “Hypnotize” and the rockers were raging against [insert whatever trend was popular among the guidos here], Eminem dropped The Marshall Mathers LP and suddenly the lines blurred.

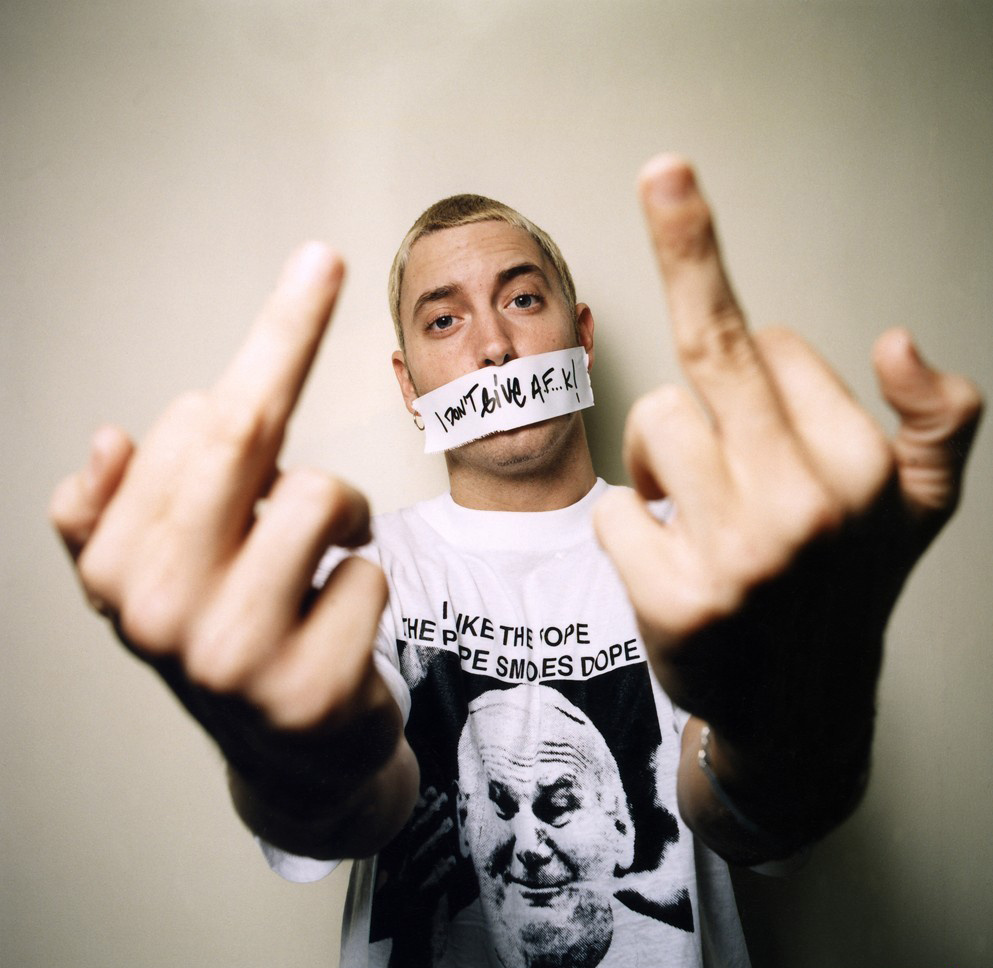

Eminem was the one artist high school kids seemed to unanimously connect with. Of course he was. He represented everything high school years are about: blind rage, misguided rebellion, adolescent frustration. He was like a human middle finger. An R-rated Dennis the Menace for a dial-up modem generation.

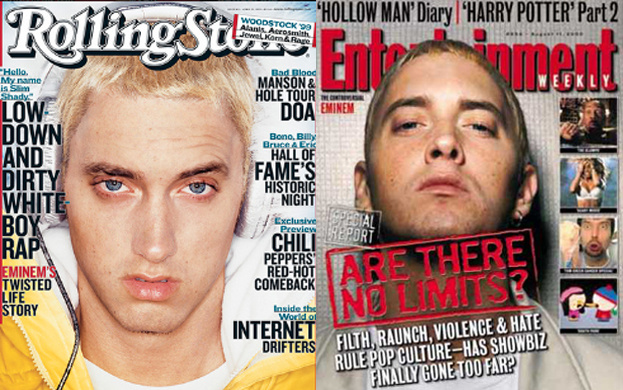

On the record’s release date, my school was a ghost town. Guidos and rockers alike cut class to go buy the CD at Sam Goody. This being during the rise of music-sharing programs like Napster, some entrepreneurial kids with fast enough internet connections were soon burning copies to sell outside their lockers. Everyone was talking about it. I found myself having in-depth musical conversations with kids I’d managed to avoid since freshman year. So deep was my hometown’s love of Eminem that a Rolling Stone cover story on him in 1999 centered around a show at a local venue where a female fan, possibly even a classmate of mine, boasted about touching his dick.

Continued below…

The road leading to this level of regard was tough. After Eminem’s seldom mentioned debut album Infinite tanked upon its release in 1996, the Detroit rapper adopted a new persona for himself. He developed Slim Shady, an alter-ego who made his debut on his follow-up 1999 album, The Slim Shady LP.

Slim Shady was Eminem letting the vitriol and insecurities of his id run amok through cartoonishly gratuitous violence. Most of the album’s themes centered around things teenagers identify with—being broke, working minimum wage jobs, getting beaten up, trying to get laid in the backseat of your Ford Shitbox. In this fantasy world, every single person who crossed Slim was exacted revenge upon in brutally sadistic fashion. On one song, a childhood bully whose real name, DeAngelo Bailey, was used got mercilessly beaten with objects from a janitor’s closet (and in real life, Bailey subsequently sued Eminem). On another, his baby daughter served as an accomplice while her mother’s corpse was stuffed into a trunk and dumped into the ocean (a scene also depicted on the cover). And on the album’s single “My Name Is,” his English teacher who tried to flunk him famously got his nuts stapled to a stack of paper.

But Eminem’s true gift was making the violence and anger funny. His humor served as an effective communication tool to lure in a new generation of rap fans. He weaved together semi-autobiographical real-world elements with vivid imaginaryland settings through puns, turns of phrase, and double entendres that were more clever than he’s often given credit for as a shock rapper. Reviews were largely positive, but even the not-so positive ones at least did him the courtesy of praising his comical creativity and extensive vocabulary. Critic Nathan Rabin at The AV Club noted that aside from Slim Shady sometimes being “sophomoric and uninspired,” Eminem’s “surreal, ultraviolent, trailer-trash/post-gangsta-rap extremism is at least a breath of fresh air in a rap world that’s despairingly low on new ideas.” But not all the adults were laughing.

While The Slim Shady LP launched Eminem into new levels of fame and wealth, his newfound celebrity came with an angry mob who labeled him a misogynist, a homophobe, an advocate of domestic violence. Timothy White, Billboard’s editor in chief at the time, claimed Eminem was “making money by exploiting the world’s misery.” Advocacy groups and concerned parents came out of the woodwork. Even Eminem’s own mother filed a lawsuit against him for claiming she did drugs on the album, from which she received a mere $1,600, falling just $10,998,400 short of her asking price. Everyone wanted Eminem to shut the fuck up, which would explain the promo photos of him with duct tape over this mouth.

There are two ways you can take that sort of negative criticism where people vilify you as a monster. You can let it push you down the shame spiral until you publicly apologize and walk away castrated with your tail between your legs. Or, you can double down and embrace the monster persona. Eminem tripled down. He quadrupled down. He downed until there weren’t numbers high enough.

After a year of getting grilled under the public spotlight, he released The Marshall Mathers LP in 2000, his 72-minute all-capsed FUCK YOU to the many enemies he’d racked up along his rise from Slim Shady. It was Eminem’s kneejerk reaction and yet it was intricately layered and brilliantly crafted. The playful crayoned lettering that adorned the cover of The Slim Shady LP was gone. This was a new Eminem. A darker, more cynical Eminem. He was less of a juvenile jester and more a full-grown disgruntled adult. And if you were only listening to the album to hear what Eminem thought of the criticism surrounding him, good news, he had an answer for you: He just did not give a fuck.

That’s sort of the album’s main takeaway: The self-proclaimed “Mr. Don’t Give a Fuck” heard your concerns about how he was ruining the country loud and clear, he just didn’t care.

His response to his supporters wasn’t much warmer. On “The Way I Am,” the album’s reaction to the pressures of having a rabid fanbase pop up overnight, you can hear Eminem seething in his rhymes. “I don’t know you and no, I don’t owe you a mothafucking thing. I’m not Mr. N’Sync, I’m not what your friends think. I’m not Mr. Friendly, I can be a prick.” He may have found an audience of suburban teens molding themselves after his image, but he also made it clear that he had no interest in being their friend or their role model.

After he addressed the laundry list of pre-existing criticisms against him, he rattled off about a million new reasons to hate him—mocking recently deceased or paralyzed celebrities, popping Viocodin, sodomy, arson, suicide, cop killing, animal decapitation, pop star impregnation, Juggalo threatening, drunk driving, women slapping, autism mocking, President sexualizing, homophobia, and hate crimes. Hate crimes by the truckload. Like he said, he was the “the bad guy who makes fun of people that die in plane crashes and laughs as long as it ain’t happened to him.”

The homophobia issue was a lightning rod for hatred of Eminem, and it’s easy to understand why. His gay-bashing was unabashed. To take a cursory listen to the album, you’d hear lyrics like:

“My words are like a dagger with a jagged edge

That’ll stab you in the head, whether you’re a fag or lez.

Or the homosex, hermaph, or a trans-a-vest.

Pants or dress, hate fags? The answer’s ‘yes.’”

No real two ways to take that. Eminem was confronted about this—and still is—in numerous interviews and he’d usually stick to the same story—that his songs are fictional narratives or, at most, extremely exaggerated realities. He’d often compare his songs to horror movies and would mention that he has no real-life problems with gay people (a point he’d later try to publicly drive home with his Grammy performance with Elton John, which was protested by GLAAD). It was a baited trap to fall into. If you took the album’s homophobia seriously, did you also take the rest of the tirades in earnest? Did you believe its prominence of bestiality and celebrity murders and armed robberies to be true? On one song, one of Em’s accomplices brags about having ten of his friends gang-rape his own sister as her birthday gift. Is that something you believed as well? Eminem was daring you to step into his deranged funhouse where you would come out forgetting what you even believed.

People like to look back at offensive iconic pop culture relics like The Marshall Mathers LP and tell themselves that that sort of thing wouldn’t fly today—that we’ve made enough cultural advances in the acceptance of gay culture and women’s equality for Eminem to be thwarted by social justice warriors and outrage-bloggers today. And maybe that would be true of the outright gay-bashing and misogyny on Eddie Murphy’s classic comedy special Raw or the racially-charged social commentary in Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles. But not for Marshall Mathers.

While The Marshall Mathers LP definitely would have enough un-PC material on it to keep Slate’s entire current staff thinkpiecing into the next millennium, Eminem wore an armored battlesuit built of pure no-fucks-given. This was an album for the kid who knew what he was doing would get him grounded so he enjoyed the hell out of it while he could. As the album’s intro “Public Service Announcement” warned: “Slim Shady does not give a fuck what you think. If you don’t like it, you can suck his fucking cock. Upon purchasing this album, you have just kissed his ass. Slim Shady is fed up with your shit, and he’s going to kill you.”

There was no point in calling Eminem out. He already did it for you and offered you a response right there on the album. In the very first verse, he joked about sexually assaulting his mother before mocking the would-be response from his critics. “Oh now he’s raping his own mother, abusing a whore, snorting coke, and we gave him the Rolling Stone cover?” he clucked out of the side of his mouth, his impression of society’s take on him. He laughed back defiantly: “You goddamn right, bitch, and now it’s too late. I’m triple platinum and tragedy’s happened in two states.” The joke was on you for making him famous.

There were numerous other occasions where he hinted at self-awareness and then laughed in the face of repentance. “Apology?” What did that word mean? It wasn’t one in Eminem’s vocabulary—not enough room between “anus” and “asshole.”

And in a truly brilliant move of next level trollery, Eminem made a last minute addition to the album before it went to press. In the middle of this incredibly dark record teeming with vile condemnation of pop culture, he stuck in “The Real Slim Shady,” a track satirizing Top 40 music which also happened to have a hook upbeat and catchy enough to get it radio play. And it worked. Despite making light of the domestic violence issues surrounding then celeb power couple Pamela Anderson and Tommy Lee, proclaiming “fuck you” to box office golden boy/inoffensive rapper Will Smith, and accusing pop star Christina Aguilera of giving him VD, it hit number four on the Billboard list. And just like that, Eminem got rich off of the same system that demonized him. Congratulations, America, you were fucking played.

Then there were the guest verses. It’s funny looking back 15 years at The Marshall Mathers LP from a present where the world’s biggest rap stars are turning to a 72-year-old Beatle for collaborations. Aside from a brief appearance by Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre (the album’s producer who also incidentally got “killed” on a song), Em completely eschewed any star power. Instead, he went out and assembled a ragtag crew of hip-hop misfits who were too menacing, too raunchy, and too downright odd to fit in anywhere else. They were the undesirables of the genre, twisted minds who sounded straight out of prison or a psych ward, and Eminem put them front and center on one of the bestselling albums of the decade. And for his good faith, his merry band of psychopaths did not disappoint.

“Remember Me?” was a song performed by the fantasy rap team of your nightmares, featuring verses from RBX and Onyx’s Sticky Fingaz who combined to drop red flag phrases like “retarded” and “dyke bitches” and made references to mother-raping and “fucking bitches raw.” And just to remind you that he would not allow his abhorrence to be outdone on his own song, Eminem wrapped things up with a verse about the Columbine High School shootings, a tragedy that wasn’t even a year old when he recorded it. And then threw a gratuitous “faggot” on the end of it for good measure. On another song, Eminem handed the mic over to fellow D12 member Bizarre who was relatively unknown at the time (and, let’s be real, still is), and he launched into a whopper about fucking his pitbull while on an acid trip and needing to get it an abortion.

Over the course of his proceeding albums, Eminem’s unquestionable talent as an emcee remained, yet he was never again able to capture that pure, unadulterated hatred in a bottle he had an endless supply of on The Marshall Mathers LP. Maybe he finally adjusted to the stardom of being the world’s most famous shock rapper and the large-scale backlash that comes with it. Maybe he grew tired of the game he played with white America, dropping blood into the shark tank and watching them work themselves into a frenzy. Or maybe we all got older and the idea of a man in his forties harassing teenage boy bands grew stale.

It’s been 15 years since The Marshall Mathers LP was released. Sometimes I’ll throw it on and scroll through Facebook. From what I can gather from following my old high school classmates, most of them have grown up, settled into careers, and some have plunked out a couple of kids. I haven’t. I wonder what they think of me now, the rockers and the guidos. To be honest, I don’t really give a fuck.

Dan Ozzi is whatever you say he is. Follow him on Twitter – @danozzi

More

From VICE

-

Slaven Vlasic/Mike Marsland/WireImage/Getty Images -

Charles Sykes/Bravo/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversa/Getty Images -

(Photo by Carlos Alvarez/GC Images) -

Apple TV+