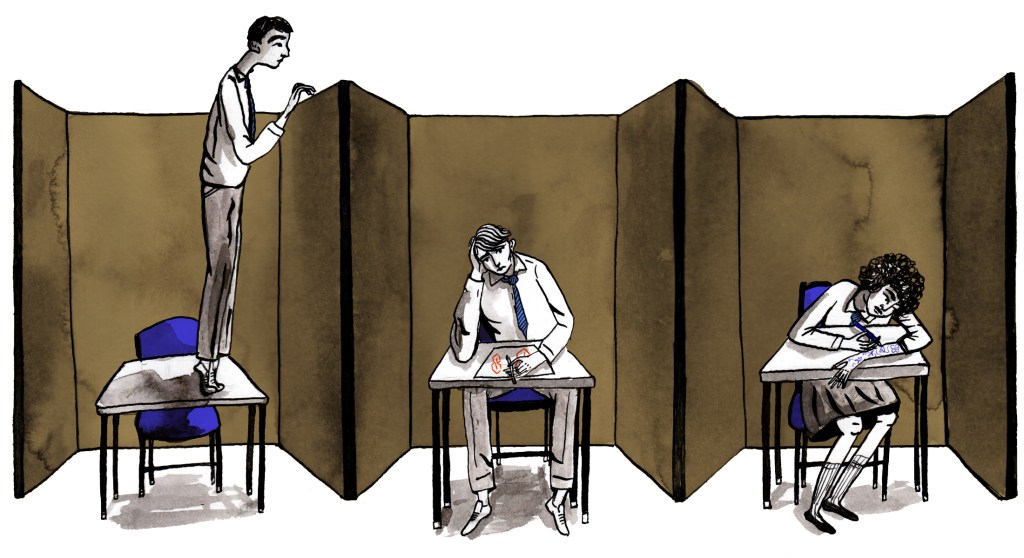

Matty still remembers what school isolation was like because he often goes back there in his dreams. The cubicles were cramped and dark with students’ graffitied initials carved into the wood. It was silent except when the rest of school went out for lunch and you could hear laughing in the canteen below. Teachers would hand him a thick pile of work, most of it easy maths sums like “3 x 7” or questions about plant cells, and all of it wholly irrelevant to anything he would need for his upcoming GCSEs. The next day Matty came in, he would be given the same pile of worksheets that he had completed the day before.

His head fuzzed and blurred with boredom. Sometimes it felt like he couldn’t breathe in there. Another day of isolation was added on every time Matty rested his head on the desk, and another when he rocked his chair back, hummed the Match of the Day theme, or was caught with his top button undone. After a week in the cubicle, he started to feel trapped and stopped coming into school – he got more isolation for that. He didn’t tell his mum what he had been through. He didn’t want to make her angry.

Videos by VICE

Sometimes he was put in isolation for bullying; sometimes for turning up to school late, or smoking weed during lunch time. One time he was sent there for answering his physics teacher back. They had said a formula was 98 percent correct and Matty shouted: “How can it be science if no one’s proved it is factually correct yet?” The teacher initially ignored him, but sent Matty to isolation when he persisted his line of questioning.

Matty and I went to the same school, a state school turned academy in Otley, West Yorkshire. There’s no way I would have been punished for asking that question. The teacher would be more likely to indulge my curiosity or make a joke about how it didn’t matter what I thought as long as I ticked the right box in the multiple choice paper. Maybe it was because I was blonde and shy. Maybe it was because my dad turned up to every parents evening in a tie. Maybe it’s just because teachers just thought Matty was a bad kid.

Matty is now 24. He struggles in social scenarios and often gets anxious – something he believes being locked away for seven hours a day on his own has not helped. But he has come out of the experience untouched, compared to some kids. In 2019, a girl on the autism spectrum tried to overdose in her isolation booth after spending a month of her school hours in there. Before that, a boy with ADHD attempted suicide after falling into a “cycle of regular confinement” from the age of 11 to 16.

Despite a lack of research into its impact on young minds, the practice of isolation is becoming increasingly widespread. Schools Week sent a Freedom of Information request to the 90 largest academy trusts asking if they use isolation rooms. A total of 71 responded, of which 68 percent confirmed at least some of their schools used these rooms. Why has such an extreme form of discipline become so normalised within UK state schools? What happens to a young person after they are held in solitary conditions for up to eight hours a day?

The origins of isolation as a disciplining procedure in schools are relatively unknown. Paul Dix, a teacher and campaigner against isolation with charity Ban The Booths, says caretakers used to build the cubicles out of makeshift materials. Dix believes isolation grew to prominence in the 90s after one Birmingham school reported an improvement in grades after booths were installed as a form of punishment. But it is only in the last ten years that isolation has become a major part of the education system, with kids who previously would have received counselling sessions or help from onsite social workers finding themselves locked away.

Unlike exclusions, schools are not required to record the number of pupils sitting in isolation, meaning schools can lock kids away without receiving any sanctions from Ofsted. The guidelines on what pupils can be put in isolation for are equally vague. The Department for Education (DfE) simply states that they can be held for “a limited period of time”, which is left to schools to determine, before mentioning that teachers should “act reasonably in all circumstances” and any use of isolation that prevents pupils from leaving a room “of their own free will should only be considered in exceptional circumstances”. In practice, this has lead to kids being in isolation for weeks at a time for anything from swearing to coming in with the wrong coloured socks.

While not strictly classed as solitary confinement – according to the UN, solitary confinement refers to people without contact with others for 23 hours or more – it is a lesser form of the same practice. “It’s jail,” says J. Wesley Boyd, a psychiatrist at the Centre for Bioethics at Harvard Medical School. “I mean, call it what you want, you get to go home from jail, but it’s still jail during the school day.” Wesley’s diagnosis is concerning when you consider that, in 1990, the UN made rules prohibiting “disciplinary measures constituting cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment including solitary confinement or any other punishment that may compromise the physical or mental health of the juvenile”.

Aside from potentially increasing anxiety, paranoia and anger issues, Wesley believes isolation will damage social skills and harms a child’s ability to conform to the rules. “One element of social situations is that you’re practising all the time, looking at people and figuring out their responses to your words and how you can do it differently next time. Put someone in isolation and none of that is happening.”

Matty was not the only kid put into isolation for reasons that may sound arbitrary to some. Mared, 22, went to a Welsh-speaking school in Snowdonia. She was, as she describes, “not a bully or anything, just gobby” and was mostly sent to isolation for disrupting class: pinning sanitary pads on backs, passing notes, chatting to friends.

“One time a teacher was being overdramatic when everyone was walking into the class, screaming ‘quiet everyone’ so I pretended to tiptoe in,” Mared says. “She threw me in isolation for a couple of days for that. Another time I walked into my biology class and I remember the teacher just shouted ‘out’.” After weeks of being in isolation for long periods of time, she became frustrated and ran away. “I was like ‘fuck this, I’m off to get a sausage roll from town.” For that, she received more time in isolation.

Wednesday, 19, went to a state school in Todmorden, West Yorkshire. She often ended up in isolation for refusing to do work. She would storm out when teachers asked her to read aloud from textbooks, rip up worksheets when she was told off for not completing them, and refuse to speak when they picked on her during lessons. She says that she was acting up because she was scared; if she got something wrong, other students would laugh and call her stupid.

Alongside severe dyslexia, Wednesday has Irlene Syndrome (a.k.a scotopic sensitivity syndrome), a perceptual processing disorder that makes it difficult to read off white paper. “I can’t process the writing into a language that my head can recognise,” she says. “The words jumble around; I can only recognise one letter at a time and I can’t see spaces sometimes – everything conjoins into one big blur. It’s a lot easier if I read from yellow paper, then everything gets weighed down and it’s easier to read.”

While the school knew that she had dyslexia, no one picked up on Wednesday’s other reading difficulties. She didn’t receive spelling help or yellow paper. Intimidated by the large class sizes and unable to keep up with the pace of work, Wednesday says she purposefully misbehaved so she would be sent out. “In isolation there were only four or five people rather than 30 so you got more help from teachers,” she tells me. The work was also a lot easier so Wednesday could actually get something done during the day. Sometimes the support worker would let them do more creative activities: “We would paint flowers and trees and all that hippy shit.” The grey booths became a safe space for Wednesday, who often felt overwhelmed in her regular class. “I actually really enjoyed it in there. Being in isolation was a good place for me to be in school.”

Wednesday is one of the few people I spoke to who found comfort in the cubicles, but she admits that there should have been better ways of making sure her needs were met. “Being naughty so you get more support is not nice,” she says. “No one should have to do that – ever.”

Much like adults in prison, those that end up in isolation struggle to escape the system. Bored students develop coping mechanisms to try and reduce stress; Matty would scrape away the foamy filler separating booths and send notes to the kid next door – big cartoon dicks or geometric ‘S’ shapes. Mared would doodle in biro all over her arms. Wednesday would lean back in her chair and hum, whistle or sing. When they were caught doing these activities, extra days would be added onto their time in isolation, making escape increasingly difficult. The Guardian reports that Outwood Grange Academies Trust, which runs 30 schools, does not allow pupils in isolation rooms to look left or right, chew, tap or sigh.

“There used to be a window so you could look out of your isolation booth,” Wednesday told me. “One day they covered over the window. A lot of kids found that really difficult because you couldn’t see out anymore and so they stopped coming in as much – it’s like they realised they were trapped.” With nothing to look at but a blank wall, the behaviour of Wednesday’s classmates worsened. Some of them dropped out of school altogether.

Why is isolation still so common in UK schools? Dix says that blame lies with an entrenched idea in Britain that you can punish away bad behaviour. “I was talking to a head teacher who was saying, ‘we had detentions from Monday to Friday every night, and that wasn’t working so we put on a Saturday morning detention.’ I said to him, ‘what’s the plan now because it’s still not working?’ And he said ‘Sunday morning detentions’. This is trauma-informed practice and it’s not dealing with the real issues behind bad behaviour.”

For Paul Williams, a Labour MP for Stockton and a vocal critic of isolation, the fault lies with an overemphasis on test results in the school system. A 2017 study by Department of Education tsar Tom Bennett managed to demonstrate statistical associations between isolation and better grades in school, but Williams says that disregarding a small portion of the class with behavioural issues in order to focus on the grades of high achievers is an elitist way of approaching education.

“Instead of a school being inclusive and trying to bring on everybody, it is writing people off,” Williams told me. “The long term costs to our society are astronomical. These are the young people that don’t get that investment, they don’t get the results that they need, so they don’t end up getting the work that they need. I’m not saying it always leads to poor outcomes but it can exacerbate. It’s a slippery slope, if we had invested in them at the right time then we could have avoided that.” Mared says that most of the people who were regularly in the isolation booth with her either are in jail, or have been in the past.

It appears the practice of isolation will continue to operate in schools, though the government is set to clarify the regulations on the practice in the next few months. When asked about their policy on isolation, a spokesperson for the Department for Education responded: “All schools should be safe and respectful environments, free of disruption, where pupils feel happy and able to fulfil their potential.” They also said that the government-commissioned Timpson review into exclusions “identified that the effective use of isolation and other forms of in-school unit can provide a positive alternative to a child being excluded but that there was too much variation in their use.”

“To support schools, we have committed to publishing clearer, more consistent guidance on managing behaviour and on the use of such in-school units,” the spokesperson added. “We also recently announced a £10 million investment to set up school behaviour networks, to enable schools to share best practice on behaviour and classroom management.”

Isolation still causes issues for those who went through it, years after they have left school. Mared has had panic attacks her whole life and now believes that the hours she spent in confined spaces might have contributed towards them. Wednesday says her problems at school has left her with permanent outsider syndrome. “You start feeling that you’re being pushed out, like you’re different from everyone else,” she tells me. “People look down on you and make you feel like shit. Throughout life you question whether you’re good enough: Is this alright? Am I worth this? Should I be here?”

Matty says being left alone for long periods might have heightened his social anxiety. “I struggle when I meet people for the first time,” he tells me. “It was really bad a couple of years ago. I would see someone twice [and] think, ‘Fucking hell, I need to make sure I don’t see this person a third time because I don’t know what to say.’ It is not because of them, it is just [my] mind.”

He also thinks isolation has made his anger problems worse, although he has now sought treatment and attends counselling sessions in Leeds. “I bottle a lot of things up and once that bottle is full I can’t control myself,” Matty told me at the end of our phone call. “Being stuck in a room like that you end up dwelling on your thoughts more than you should. It’s mental torture.”

There are ways of getting young people to listen at school that aren’t locking them up in an enclosed booth. What would have happened if teachers had kids go to a counselling session? Or stopped caring that they brought in the wrong coloured pen? Or explained why all physics sums aren’t 100 percent correct yet? Perhaps the lives of a whole generation of students would have turned out differently. to have someone on their side, rather than someone against them; to not always feel like a burden; to get the resources they needed, and to have someone talk to them and listen when they said it hurt.

More

From VICE

-

Nick Fuentes, a white supremacist streamer and US social media pundit, appears to mace 57-year-old Marla Rose, a 57-year-old on his doorstep on Sunday, November 10 (Imagery courtesy of Marla Rose) -

Screenshot: Shaun Cichacki -

Mykola Sosiukin/Getty Images -

Photo by © Hans Barten